The Smartest Guys in the Room: Management Lessons from Enron’s Leaders

Enron is a story about America’s largest corporate failure at that point in history—and a story about human tragedy. Enron’s rise and fall is the focus of numerous articles in the mainstream, trade and scholarly literature along with mass market books as well as the movie that forms the basis of this paper, “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” (Gibney, 2005). However, in the words of Stein and Pinto (2011), “Our understanding of what transpired at Enron is by no means complete.”

Enron was created in 1986 from a merger of Houston National Gas and InterNorth (a natural gas pipeline company) with Ken Lay as its chair and CEO (Stein & Pinto, 2011). In 1988, the deregulation of electrical power markets took effect, and Enron transformed from a traditional natural gas energy company focused on energy delivery through gas pipelines to an energy broker company that brought buyers and sellers together (Sims & Brinkmann, 2003). Enron transformed into a high-tech global enterprise that diversified into trading energy, water, weather derivatives, broadband and electricity.

Early on, problems at Enron emerged. There was a 1987 investigation of two Enron executives at the oil trading unit in Valhalla, New York that revealed offshore accounts and phony books. The traders had gambled away all of Enron’s reserves, and Lay had known all along about the risks (Gibney, 2005).

From 1998 to 2000, Enron’s gross revenues rose from $31 billion to more than $100 billion. The financial press, however, began to ask questions about Enron’s finances. “How exactly did Enron make its money?” asked Bethany McLean, a reporter for Fortune magazine who was the first to question Enron’s finances in March 2001 (Gibney, 2005).

After September 11, 2001, the Securities Exchange Commission launched an investigation into Enron. Employees and shareholders were kept in the dark about the company’s finances. While corporate leaders assured employees that there were no accounting irregularities, they quietly sold their stock in the preceding months before the bankruptcy occurred in December 2001. Enron CEO Jeff Skilling unloaded his stock while encouraging employees to keep their shares. Meanwhile, 20,000 Enron employees lost jobs and health insurance. Everything they had worked for was gone when $2 billion in pensions disappeared. Accounting firm Arthur Anderson was convicted of obstructing justice, and 29,000 people at the firm lost their jobs. Lives that were valued at millions were reduced to $20,000. In the wake of the Enron and other corporate accounting scandals, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was passed in 2002. However, Enron should not be viewed as an aberration, but as something that can happen again (Gibney, 2005).

This article will not focus on the accounting scandal—the mark-to-market accounting, the special purpose entities and the hedge funds that Enron established to prop up earnings—but the human side of a company which experienced tremendous success for a short time and then colossal failure. The focus will be on the organization’s top managers, their roles and behaviors and how these contributed to managerial successes and mistakes. This article will examine how these managers shaped the organization’s corporate culture and changed management strategy which was the foundation of the organization’s early successes and later failures.

Management theories, such as the Competing Values Framework (CVF; Quinn, Faerman, Thompson, McGrath, & St. Clair, 2011, p. 15), offer a lens by which we can view managers and organizations. Theories reflect a perspective on organizations and management and are “about mobilizing ideas, arguments and explanations to try to make sense of practice, but also to try to influence practice” (Grey, 2009, p. 16). These theories will provide a framework by which to analyze organizational and managerial strengths as well as weaknesses.

The Competing Values Framework (CVF) is depicted as a circle with four quadrants: compete, control, collaborate, and create (Quinn at al., 2011, p. 15). This framework integrates management models developed over the years and seeks to assist both organizations and managers in balancing opposing managerial concepts, such as efficient processes versus change and innovation; adaptability and flexibility versus stability and control; respect for employees versus setting demanding goals. This versatile framework will be used to assess Enron as an organization as well as key competences demonstrated by managers that are aligned with each of the four quadrants, and in addition, it will be used to characterize the culture of the organization.

The Mintzberg triad (2009, p. 11) views the practice of managing as a blend of art, craft, and science and is used to describe management and managerial postures of individual managers. This triad will be used to show that the top management team displayed similar managerial practices and postures.

Within the broad frameworks of these models, the peer-reviewed literature will be used to highlight specific managerial successes and mistakes and the positive and negative effects on the organization and culture of Enron. This will be illustrated by examples drawn from the movie, “Enron: the Smartest Guys in the Room” and augmented with other accounts of Enron in the trade and mainstream media as well as the peer-reviewed literature.

The Faces of Enron

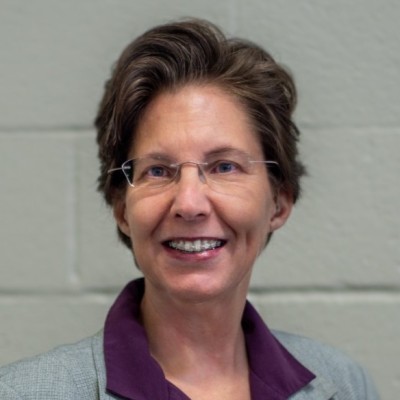

Although there were other players that comprised Enron’s top management team, Figure 1 describes the following key figures in Enron’s top management team as featured in the documentary “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” (Gibney, 2005).

Many of Enron’s top leadership as well as their employees had a constellation of very similar personality characteristics, educational backgrounds and life experiences. These corporate leaders came from families that were not well-off and they had tremendous motivation and drive to overcome the past and make a better life for themselves in the world. Enron Chairman and CEO Ken Lay was the son of a Baptist preacher and had been poor all of his life. His parents had little formal education, but Lay dreamed of the world of business and went on to earn a Ph.D. in economics (Gibney, 2005). Sherron Watkins, a company vice president, was born in Tomball, Texas, and was raised by a single mother who taught business at the local high school and encouraged her to go into accounting, which Watkins did, earning a master’s degree in accounting (Swartz & Watkins, 2004).

Both the management team and employees were intelligent, ambitious and “tightly wound” individuals who typically worked 80 hours a week, according to Schwartz and Watkins (2004). Cliff Baxter, vice chairman of Enron, was extremely intelligent and extraordinarily talented at making deals but also was manic depressive and later committed suicide after the company went bankrupt. Jeffrey Skilling, chief operating officer and CEO, was a Harvard graduate who was described in the movie as “incandescently brilliant”—and like many in the Enron leadership—was also described as a “nerd.” After his divorce he sought to shed his “nerd” image and, through sheer force of will, to remake himself into a more dynamic individual with a better fashion sense. He dispensed with glasses, got Lasik and outfitted himself with a new wardrobe (Gibney, 2005).

Many of the top managers were up and coming, under-40 professionals who lacked the ability and interest in managing their young and ambitious often 20-something staff. Chief Financial Officer Fastow was described as a “PowerPoint executive whose number-crunching talent far exceeded his managerial and people skills” (Saporito, 2002). Lou Pai ran Enron Energy Services and “dispatched enemies with incredible skill” but the business was all about the numbers to him, according to the movie. Despite having a staff, he was seldom seen in the office (Gibney, 2005). Other executives were playful but also prone to unleashing temper tantrums in the office (Schwartz &Watkins, 2004).

Based on these brief descriptive snapshots of these managers, they might complete the assessment developed by Mintzberg and Patwell (2008, as cited in Mintzberg, 2009, p. 128) by describing how they manage their job in the following terms: ideas, strategies, novel, imagining and “The possibilities are endless!” This suggests that they leaned toward management as an art, using vision and creative insight to guide their work. At the same time, they would describe their work in these terms: analytical, head, informing, reliable and “doing it.” This suggests that they leaned toward the science aspect of management, drawing on the analysis and systematic evidence of data and numbers, combined with action and a bit of the craft of “doing it.”

These qualities suggest that all of these managers were predominantly oriented toward the managerial posture of “connecting externally” (Mintzberg, 2009, pp. 136-137). This posture is often adopted by senior managers whose focus in on connecting with others outside the organization and with navigating external political and marketplace forces. These managers engage in deal making, negotiating and networking. They are the “gamesmen” of the organization (Mintzberg, 2009, p. 137). Because of their external focus, these high-ranking managers depend on others to handle internal operations and they exercise little control over internal staff.

Some of these managers, such as Lou Pai, took this posture to an extreme and would be viewed as reluctant managers (Mintzberg, 2009, p. 146). Given that he was seldom in his office, Pai had little interest in managing employees, favoring the role of practitioner, dealer, and entrepreneur within the organization.

There were some, however, notable differences among the top managers in the organization. Sherron Watkins came from a similar background as many top Enron managers in that she grew up in the small town of Tomball, Texas and had the ambition of climbing the corporate ladder. At Enron, she was somewhat of an anomaly because she was nearly 40 years older, making her older than many colleagues. She was one of few women in upper management and among these women, one of the few who had a young child, although she carefully hid her pregnancy for as long as she could in the male-dominated environment of Enron in her pursuit of a vice president position (Schwartz & Watkins, 2004). Among a management team where divorce and infidelity were common, Watkins was one of the few who was married. These demographic factors may have set her apart from the rest of the management team. She was also known to be outspoken (Duffy, 2002), a quality that could have extremely negative career repercussions at Enron. It is unclear from either the movie or her own book (Gibney, 2005; Schwartz & Watkins, 2004) exactly what propelled Watkins to become a whistleblower and her specific motivations to send the infamous letter and to follow-up this communication with additional meetings and memos; however, the differences that set her apart from other managers may have facilitated these actions.

The remarkable similarity among the top management team in personality characteristics, life experiences, and educational background in combination with uniformity in management styles and predominant managerial postures led to a leadership team that was highly imbalanced. The strong uniformity among the management team and their hands-off management style led to a weakness in internal control that, among other factors, contributed to an environment that was ripe for ethical lapses.

Charismatic Leadership

Enron was led by charismatic leaders Ken Lay as well as Jeff Skilling who was said to have “radiated so much charisma that he induced blind obedience in his followers” (Khurana, 2002). Charisma is a sought-after quality among corporate leaders (Khurana, 2002) and one that has been correlated with leadership effectiveness (Hoffman, Woehr, Maldagen-Youngjohn, & Lyons, 2011), but when overdeveloped, charisma is a quality that can lead to the dark side of leadership.

As charismatic leaders, Lay and Skilling had a clear and compelling vision for the organization and were skilled in communicating their compelling vision of Enron and its culture to all stakeholders—employees, shareholders, the media and the public—that the company was “the most innovative culture in America” (Murphy & Ensher, 2008).

Charismatic leaders are also characterized as having heightened sense to the environmental context of the organization and the ability to scan for environment for trends that might require them to change their vision (Murphy & Ensher, 2008). Ken Lay, for example, was acutely aware of the regulatory context of the business and believed that energy markets should be deregulated and lobbied tirelessly for change on Capitol Hill. The power of deregulation gave rise to new business opportunities for Enron. However, Lay also had sensitivity to the nature of politics and the need to maintain relationships with politicians and became the largest contributor to the George W. Bush campaign.

Lay, Skilling and other top leaders such as Andy Fastow, also demonstrated risk-taking and deviation from the status quo, a characteristic found in charismatic leaders (Murphy & Ensher, 2008). Fastow was the creator of hundreds of special purpose entities—risky investments named after Star War’s characters that were designed to transfer Enron’s debt outside of the company and get it off the books (Saporito, 2002; Schwartz & Watkins, 2004).

Charismatic leaders can bring much strength to their organizations, but this same characteristic has also been defined as a “key ingredients of cultic dynamics” in Enron leadership (Tourish, & Vatcha, 2005). Charismatic leaders may have a self-schema that reflects a propensity toward authoritarian control (Murphy & Ensher, 2008), a defining characteristic Enron’s top leadership, who tolerated little dissent. Managers who questioned the organization’s accounting practices or who brought concerns to Ken Lay may have left a meeting with a tacit statement that their concerns would be looked into. However, they soon experienced retaliation for their actions as their staff was removed from beneath them and reassigned to other units (Swartz & Watkins, 2004).

Cult leaders show individual consideration (Tourish, & Vatcha, 2005) or sensitivity to group member’s needs (Murphy & Ensher, 2008). Enron’s leadership did this with aplomb, protecting their top management from criticism inside and outside the organization. At a 2001 meeting designed to reassure workers about the future, Andy Fastow shared the stage with Lay who proclaimed his trust in the company’s chief financial officer—despite the fact that he’s lost nearly a billion dollars mismanaging special partnerships. Other top leaders were similarly insulated from the consequences of their actions.

In addition to charisma, Enron’s top managers exhibited other traits associated with effective leadership (Hoffman, Woehr, Maldagen-Youngjohn &Lyons, 2011). Research has highlighted 7 characteristics that have a particularly strong correlation to effective leadership: dominance, creativity, charisma, interpersonal skills, management skills, problem-solving skills, and decision making. In business settings, a trio of qualities—dominance, self-confidence and intelligence—are strongly linked to leadership effectiveness and are qualities that Enron executives displayed in abundance. Positive characteristics, however, can become leadership liabilities if overdeveloped. Enron’s leadership demonstrated dominance that led to retaliation, self-confidence that crossed the line into hubris, and intelligence that was used for cunning arbitrage.

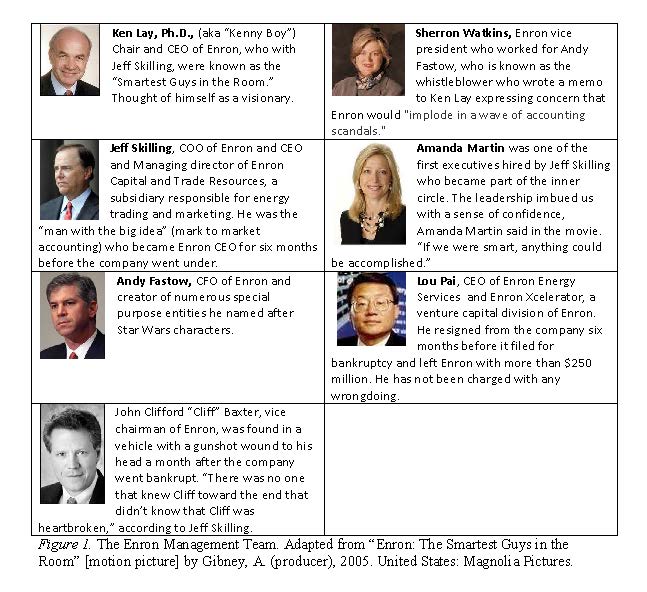

An organigraph takes the age-old organizational chart with its traditional hierarchical structure and changes it into an image that provides more information about how individuals at an organization really interact. It also depicts critical relationships, organizational structure, management philosophy and even competitive opportunities. In depicting Enron through an organigraph the characteristics and the centralized role that Enron’s management team played in the organization as well as their widespread influence would place them at the very center of the image (Mintzberg & Van der Heyden, 1999). Figure 2 shows an organigraph of Enron.

The Enron organigraph depicts the organization in a structure that is envisioned as both a cell and a planetary system. The overall shape is a cytoplasmic fluid of change as the company constantly changed its direction and restructured its internal units. At the center is Jeff Skilling, the charismatic leader who exerted the most influence in shaping the corporate culture, and who is surrounded by other top managers in a hub formation. These leaders—Ken Lay, Lou Pai, Andy Fastow, Ken Rice, John Wing and others—exert centralized influence and power throughout the organization to a degree that they have been described as a “gang” and a “super-powerful high school clique” (Stein & Pinto, 2011; Gibney, 2005).

The leadership team managed units in a hierarchical fashion, as this structure is designed to represent a traditional organizational chart placed in a cell format in a greatly simplified fashion. Some of these units formed the basis of subsidiary organizations; however, most subsidiaries are not truly separate from the main organization. The management team exerted influence and control over their employees and their focus and influence radiated outward to the external environment where they are making deals with other organizations.

The cell has various tentacles that are attached as acquisitions over the years. The bubble burst figure is the traders who traded energy commodities on the open market. Orbiting around the cell are the special purpose entities which are separate organizational structures designed to keep debt off the books, away from the main company, but these organizations are not strongly connected to the main cell body.

The Culture of Enron

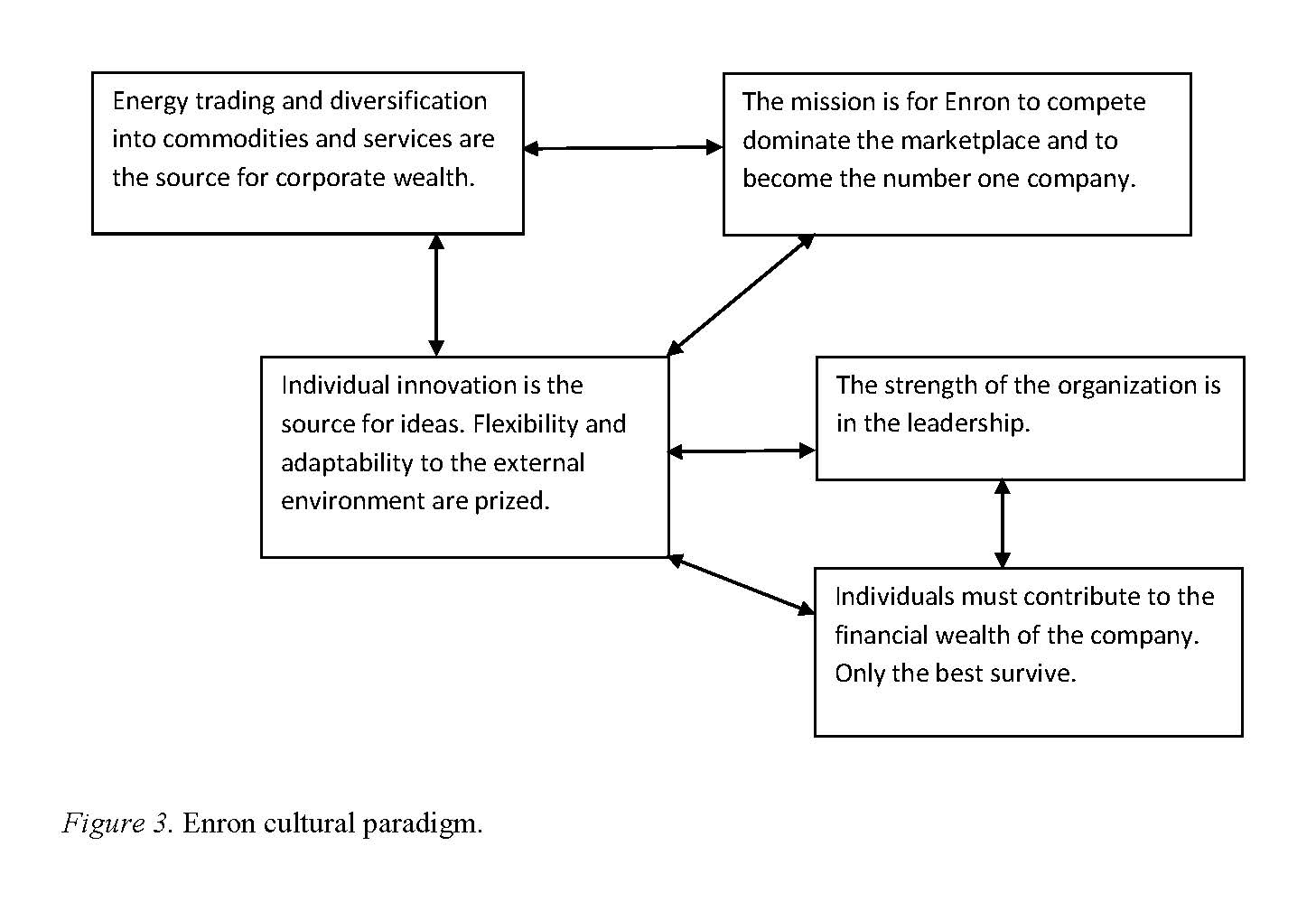

Enron’s leadership used its charisma to craft a strong organizational culture which was both an extraordinary corporate and managerial success, and at the same time, a weakness that eventually led to the company’s downfall. A cultural paradigm is a schematic which captures the underlying assumptions on which a corporate culture is based. Figure 3 describes Enron’s paradigm and serves as a basis for explaining the cultural artifacts that have emerged as the result of these underlying values and assumptions (Schein, 1990).

Ken Lay thought of himself as a visionary and surrounded himself with others that he perceived were visionaries, such as Jeff Skilling, the “man with the big idea” of an accounting treatment called mark-to-market which allowed the company to book the potential future profit the day the deal was signed. Enron’s leadership developed a set of very clear cultural values that were explicitly and repeatedly communicated to employees and guided their actions. Enron valued innovation, creativity, change and adaptability, and competitive dominance of the marketplace—and the company richly rewarded employees who achieved these objectives. The deregulation of the energy market was a “critical incident” that shaped Enron’s culture because the company was no longer bound by the regulations that directed traditional gas pipeline companies; Enron was now able to exercise creativity in diversifying into an energy trading company (Schein, 1990; Sims & Brinkmann, 2003). This creative vision enabled Enron to embrace change and adapt to the marketplace in transforming from a traditional energy company to one that diversified into brokering energy, broadband services, electricity and weather derivatives (Gibney, 2005).

Enron’s values suggest a strong orientation in focusing on the external marketplace environment and in differentiating the organization which align the organization with both market and adhocacy cultures on the CVF (Quinn et al., 2011, p. 230). The market culture is primarily concerned with competitive dominance and attaining company goals and objectives. Within the organization, leadership is concerned with productivity, performance, and goal achievement. An adhocacy culture is concerned with flexibility and change with a focus on growth as the organization adapts to an ever-changing external marketplace. As we have seen with Enron, leadership in an adhocacy culture is entrepreneurial and idealistic and willing to take risks to achieve its vision for the future (Quinn et al., 2011, p. 230).

Employee’s strong identification with powerful and charismatic leaders shaped their internalization of the company’s values which were clearly, frequently and fervently articulated. Enron’s leadership “took free marked and turned it into an ideology and pitched it like an economic religion,” recalled Amanda Martin in the movie (Gibney, 2005). These values shaped the underlying dimensions of Enron’s culture which are listed in Table 1 and will be highlighted throughout this section. The cultural fabric of Enron was a backdrop that played a strong role in fostering Enron’s managerial success and mistakes which led to the organization’s notorious ethical lapses.

Enron’s managers perpetuated the culture of the organization beginning with the hiring process when managers typically look for employees that demonstrate the right “fit” with the organization in terms of their existing beliefs and values and then begin to acculturate new employees with these values (Schein, 1990, p. 115). Managers also perpetuated implicit biases in hiring employees much like themselves (Banaji, Bazerman, & Ch

| Dimension | Characteristics |

| The organization’s relationship to the environment | The organization perceives and markets itself as an “innovative organization.” It takes a very dominant, aggressive perspective approach to the marketplace. |

| The nature of human activity | The overall corporate culture is very masculine, macho, and male-dominated. Employees must believe in themselves. Employees must contribute to the earnings of the company to survive. People must behave in a very proactive, confident, dominant manner. |

| The nature of reality and truth | The nature of reality and truth is socially constructed by the CEO and the top management. Employees must ascribe to Ken Lay’s visionary perspective about the future growth of the company and his ideology about the free market as an “economic religion.” |

| The nature of time | Time moves very quickly and employees are expected to devote a major portion of time to Enron. Employees were never certain that they would be employed at Enron for any length of time because the Performance Review Committee (PRC) committee might give them a negative review. |

| The nature of human nature | Individualistic culture with each employee looking out for himself, his career survival and his wealth. It was acceptable—and encouraged—to take bold risks and to gamble. |

| The nature of human relationships | Competitive, Darwinian, survival of the fittest environment. Step on other people’s throats if it will help you advance your career. Relationships are based on personal gain. To get ahead, one must associate with people who have stature and power in the company. |

| Homogeneity versus diversity | Individuals must be innovative and solve problems to survive. A great deal of diversity and even eccentricity is encouraged. Dissent was not allowed. No one could question management decisions. No questions were asked if executives were having affairs with strippers or with each other. |

ugh, 2003)—young, ambitious, and accomplished graduates and early career professionals. Once hired, management began the multi-dimensional process of acculturation (Schein, 1990, p. 115). In the case of Enron, the acculturation process included the self-enhancing technique of imbuing employees with a sense of confidence in themselves and the organization, noted Amanda Martin in the movie (Gibney, 2005). “If we were smart, anything could be accomplished. There was the reaffirmation that this could be big.”

Leadership excelled in demonstrating managerial strengths in competencies that were strongly aligned with the organization’s market culture. These managers had a strong orientation to the compete quadrant of the CVF framework (Quinn et al., 2011, p. 21) and the ambitious and driven managers achieved tremendous productivity and profitability from their teams. Employees noted that “. . . you were expected to perform to a standard that was continually being raised . . .” and “the only thing that mattered was adding value” (Bartlett and Glinska, 2001, as cited in Sims & Brinkmann, 2003).

To meet these goals, it was not uncommon for Enron employees to work 80 hours a week or for finance employees to presented with numbers on Friday afternoon and spend an entire weekend poring over these numbers in effort to provide data that would help management seal a deal on Monday morning (Swartz & Watkins, 2004). Although setting goals and objectives for employees is a common tool for improving productivity and profitability, in the case of Enron, these goals in combination with the employee culture had powerful and predictable negative side effects. When not selected judiciously, pursuit of goals and produce a myopic focus and increase the propensity for competition, risk taking, unethical behavior (Ordonez, Schweitzer, Galinsky, & Bazerman, 2009)—all of which occured at Enron.

Revenue goals were a numbers game that was driven by a need to boost quarterly profits. Employees were constantly surrounded by indicators of the financial health of the company from the time they entered the elevator and saw the stock prices posted (Gibney, 2005). Achievement of goals was lavishly rewarded and a 25-year old-employee could receive a $5 million bonus (Gibney, 2005), a system which created tremendous external commitment from employees who developed an opulent lifestyle and knew they couldn’t attain these financial rewards elsewhere (Argyris, 1998).

The desire to sustain these rewards encouraged employees to engage in deal making and complicated, questionable accounting procedures that would help the company meet its quarterly earnings, with little concern about how this would impact the long-term financial health of the company. Enron rewarded increased revenue, which is more easily measured, instead of rewarding profitability, a more desirable outcome (Kerr, 1975).

Enron’s corporate culture had a tremendous influence on employee’s ethical decision making due to the tremendous imbalance in power in the employer-employee relationship. When there are explicit pressures to achieve sales or profit goals this can promote unethical behavior, over-riding an employee’s intrinsic ethical values or personality characteristics, such as their level of Machiavelliansm, or tendency to manipulate situations for personal gain. In this type of environment—particularly when few checks and balances existed—corporate values were stronger than individual standards. Enron explicitly communicated the message that profit at all costs was the priority: “…break the rules, you can cheat, you can lie, but as long as you make money, it’s all right” Jeff Skilling told employees (Schwartz, 2002, as cited in Ghosh, 2008).

Not only did Enron reward employees who “met their numbers” by engaging in unethical behavior, it also shaped this behavior through punishment, another means to achieve corporate compliance (Quinn et al., 2011). Enron retained only those employees who achieved targeted profits (Ghosh, 2008, p. 69). It was an aggressive, Darwinian, fear-based, punitive “rank or yank” culture that fired 15% of employees each year who did not achieve a grade of 5 or higher on their employee performance review (Gibney, 2005).

Enron’s corporate culture fueled aggressive, risk-taking behavior in the office—and outside. Mirroring his risk-taking behavior at the office in which he placed wild bets on the market, Skilling went on male bonding trips with other managers that involved engaging in activities in which participants sustained injury and risked death. These trips included bungee jumping, rock climbing, jeep races through the desert, skydiving, and other intense thrill-seeking, risky adventures.

The male-bonding trips and the corporate lore that surrounded them promoted a masculine culture at Enron and created an “old boys” network that perpetuated persistently negative attitudes held by men in both older and younger generations (Baumgartner & Schneider, 2010). There were few women among the leadership team, suggesting the most women were unable to break the glass ceiling and rise to the upper echelon. Although the research suggests strategies for women in navigating this group dynamic by inviting oneself along on male-oriented activities (Baumgartner & Schneider, 2010), the women of Enron may have been disinclined to risk life or limb in effort to penetrate the “old boys” network.

Although the research suggests that women have succeeded with leadership styles that are feminine and unique to the individual (Baumgartner & Schneider, 2010), the women managers of Enron likely adopted the prevailing cultural norms and values which should dictate both managerial style and competencies (Quinn et al., 2012) and emulated the more masculine management styles of their male counterparts that were concerned with status and authority.

Leading Change

The culture of Enron fostered the organization’s ability to lead change by repeatedly introducing disruptive innovations into the marketplace (Denning, 2005), which contributed to the company’s successful sustained growth into the late 1990s. Enron’s leadership promoted a clear vision for change with a sense of urgency that clarified the direction the company should move and promoted this message in multiple formats through multiple communication channels (Kotter, 1995). The message was presented visually the form of a banner hanging at the entrance to the company headquarters that Enron was changing “From the world’s leading energy company to the world’s leading company.” In letters to shareholders, messages related to change were reinforced with analogy to war or sports to underscore their urgency (Tourish, & Vatcha, 2005) and gave the messages a sense of urgency.

The management team was able to create a powerful coalition to support change efforts and induce employees to remove any obstacles to achieving the vision. However, these change efforts often were accomplished through nefarious mechanisms such as seeking out loopholes in California’s energy deregulation regulations to create arbitrage that would push energy prices abnormally high (Gibney, 2005).

In the end, however, Enron’s constant organizational change and diversification gave way to what Grey (2009) has termed “fast capitalism” (Grey, 2009, p. 112) in which there is a constant transformation of the organization, continual company reorganization and frequent shifting of staff to different departments and corporate structures, and the constant speeding up of work for corporate survival in the marketplace. A culture of change produced a lack of coherent organizational identity.

Management Lessons From Enron

Both the Competing Values Framework (Quinn et al., 2011) and Mintzberg’s (2009) management model are valuable in examinging the success—and failures—of Enron’s leadership and organizational culture. Each model offers a unique vantage point and holds different strengths and weaknesses. Both models converge in suggesting a wide range of skills for managers (Mintzberg, 2009, p. 90; Quinn et al., p. 21). Examples of skills drawn from both models include managing oneself and others, leading teams, mobilizing, encouraging compliance, scheduling, and leading the organization/unit.

An assessment of the managerial competencies of Enron managers depends on the manager—and the model. The CVF competencies represent management practice and theory and are derived from the research (Quinn et al., 2011, p.20). The CVF, as its name suggests, places greater emphasis on specific values in evaluating managerial competencies. Enron’s managers, for example, would not be highly rated on their ability to communicate honestly because they withheld information from employees as they neglected to communicate the true status of the company on the eve of bankruptcy (although they may have been effective communicators) or the ability to use power ethically because they used it for retaliation (although they may have wielded power effectively). Mintzberg’s model of managing places an emphasis on the roles and sub-roles that managers play and lists competencies that accompany these roles. This model is detailed, prescriptive, and action-oriented and would tend to favor Enron’s managers who excelled at competencies such as mobilizing, which includes “firefighting, project managing, negotiating/dealing, politicking, and managing change” (Mintzberg, 2009, p. 91). Although there is convergence between the competencies in these models, their divergence makes these models somewhat less valuable in defining specific skills for effective management.

While the models address leadership skills and competencies, neither addresses specific traits or personality characteristics associated with effective leadership. Inherent traits of effective leaders such as dominance or charisma are identified in the research (e.g., Hoffman, Woehr, Maldagen-Youngjohn, Lyons, 2011) and debated in the research and trade media (e.g., Khurana, 2002; Tourish & Vatcha, 2005).

Moving to a broader level, both models offer a much different perspective on Enron, but both identify key weaknesses in the management team that contributed to the downfall of the company. Mintzberg (2009, p. 11) conceptualizes managing as a practice that combines art, craft, and science. An analysis of Enron’s leadership suggests that these managers adopted managerial styles that focused on the art and sciences aspect of management, with a tiny bit of craft mixed in. These managers adopted a managerial posture of connecting externally (Mintzberg, 2009, p. 138), and some were reluctant managers altogether. This suggests that Enron’s leadership lacked balance in their individual approaches to management and that the senior leaders lacked balance in management styles that would provide different strengths, perspectives, and viewpoints to the team.

The CVF framework offers the same conclusion, but a different perspective. The management team excelled in the external-focused competencies on the compete and create quadrants, with demonstrated weakness on the opposing and competing values aligned with the control and collaborate quadrants. The strength of this model is that it also allows us to analyze the organizational culture along these same dimensions. With its strong external and competitive focus and cultural orientation to change and innovation, Enron adopted a strong market and adhocracy culture. As symbolized in the “crooked E” in the Enron logo, the imbalance in the managerial styles, organizational focus and organizational culture caused the organization to lean and then topple. Its managerial team did not integrate competing values and demonstrate behavioral complexity that would have made them more effective. Their unitary managerial posture contributed to a myopic vision and fostered a culture that was enormously successful but later became toxic.

Both the CVF and the Mintzberg model offer valuable frameworks for assessing organizations, but each model has strengths and weaknesses. The competing values framework offers a stronger perspective on the overall balance of the organization among four quadrants. The Mintzberg model offers insight into managerial posture for individual managers and teams. Effective organizational leadership teams are those that have balance among individuals who assume various managerial postures aligned with art, craft, and science, as each managerial posture brings different strengths to the organization. Both the CVF and the Mintzberg management model emphasize the wide range of skills needed by managers; however, Mintzberg’s model stresses the managerial roles and the need for action in internally and externally and on different planes. The CVF emphasizes the integration of competing values for a balanced individual approach to management.

A Model for Organizational Development

Despite Enron’s well-known weaknesses and egregious ethical lapses, Enron had key areas of organizational strength in which the organization stands as an exemplary model for organizational development. These areas of strength contributed to the organization’s extraordinary success but were overdeveloped and eventually led to the downfall of the company.

Although relatively weak in the collaborate quadrant within the CVF model, Enron’s managerial team was exemplary in promoting confidence in their employees. This removed any obstacles of self-doubt in employees and created tremendous “net forward energy” (Oakley & Krug, 1991) which was directed toward company goals. Employee confidence, however, gave way to arrogance, hubris, and a general feeling of invincibility (Sims, & Brinkmann, 2003). In the opposing compete quadrant, Enron’s managers excelled at setting goals and objectives and driving toward results. Managers set the bar high for goal attainment—and then raised it higher. They achieved incredible productivity from their employees. However, the combination of an externally focused managerial posture (Mintzberg, 2009, p. 138) and a young staff who rose through the ranks quickly with little experience and unchecked ambition contributed to the organization’s notorious ethical lapses (Sims, & Brinkmann, 2003, p. 244).

From a managerial standpoint, Enron holds many lessons for organizational development and success. Enron was led by a team of charismatic leaders who could communicate the need for change and effect change in the organization. Unlike many organizations whose processes and dynamics stifle change and innovation, Enron leadership valued creative, visionary thinkers and entrepreneurial individuals, and the leadership welcomed good ideas and acted on them. Enron’s built a strong corporate culture which valued innovation, creativity, change, and competitive dominance in the marketplace. In integrating these values into their work, Enron’s managers were proactive—rather than reactive—and initiated action to achieve their goals, taking whatever degrees of freedom their position allowed (which sometimes was quite extensive) to execute their plans.

In the final analysis, however, Enron’s managers were “success failures” (Mintzberg, 2009, p. 204), or managers whose confidence has crossed the line into arrogance. These managers are leading organizations that have been indelibly changed by their own successes in that the original strengths that made the organization successful have become weaknesses which bring the organization down (Mintzberg, 2009, p. 204).

Developing Leadership

Enron’s early success and later failure offers many valuable mechanisms for managers to explore in building their leadership capacities and in developing the organization that they serve. Enron illustrates the tremendous leadership role that managers have in establishing the culture of the organization and in understanding the mechanisms for how organizational culture evolves. Currently, many managers deny the existence of a corporate culture in their organizations or view it as something they cannot control, instead of leveraging the opportunity to shape the formal culture of the organization (Grey, 2009, p. 73). Enron succeed because it established a strong corporate culture through the organization’s response at critical junctures of the organization’s history and in the actions of its leadership in embracing and communicating key values, such as innovation, ambition, and adaptability.

The experience of Enron emphasizes the need for managers to be reflective practitioners in identifying and analyzing their own managerial style and to seek a balanced approach to management. Mintzberg (2009, p. 201) notes that “beneath incompetence are managers who are at their core imbalanced in their approach.” While Quinn and colleagues (2011) note that corporate culture will influence managerial style and the specific managerial competencies exercised to some degree, both models suggest that managers need to be balanced in their approach. Managers, for example, will want to judiciously set challenging goals for employees—but also to develop controls that prevent unethical behavior in pursuit of those goals.

It is imperative that managers are cognizant that the practice of management requires an understanding oneself as well as others and to examine their implicit biases to ensure that they are promoting diversity of thought and perspective and not hiring someone who is exactly like themselves. Although managers need not complete the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Banaji, Bazerman, & Chugh, 2003) during the hiring process, they would do well to examine their own biases along these lines. Managers with a high level of confidence and competence are skilled at being able to work with diverse individuals and to value different ideas and different work styles.

Managers need to exercise care in the goals that they set for employees and the behaviors that are rewarded. While they may be required to follow established performance review mechanisms and models established by the organization, to the extent possible managers can shape behaviors of their employees by judiciously selecting the goals that they will pursue. Managers also can be cognizant of the tremendous power they have in creating confidence in their employees that they can achieve the goals set for them and fulfill their roles with the organization. Managers can use their power judiciously and ethically to influence and motivate individuals in their unit.

Lastly, while Enron holds many valuable lessons as an organizational success, it ultimately created a toxic culture that encouraged its employees to be dishonest and rewarded greed at the expense of long-term corporate results. It is important that all managers remain cognizant of the values promoted by their organizations and to assess, using tools such as the “Vocation of the Business Leader: A Reflection” (Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, 2012), the fit between their personal and ethical values and those of their organization.

References

Argyris, C. (1998). Empowerment: The emperor’s new clothes. Harvard Business Review, 76(3), 98-105.

Banaji, M. R., Bazerman, M. H., & Chugh, D. (2003). How (un)ethical are you? Harvard Business Review, 81(12), 56-64.

Baumgartner, M. S., & Schneider, D. E. (2010). Perceptions of women in management: A thematic analysis of the glass ceiling. Journal of Career Development, 37(2), 559-576. doi: 10.1177/0894845309352242

Denning, S. (2005). Why the best and brightest approaches don’t solve the innovation dilemma. Strategy & Leadership, 22(1), 4-11.

Duffy, M. (2002, January 19). By the sign of the crooked E. Time.com.

Ghosh, D. (2008). Corporate Values, Workplace Decisions and Ethical Standards of Employees, Journal of Managerial Issues, 20(1), 68-87.

Gibney, A. (producer). (2005). Enron: The smartest guys in the room [motion picture]. United States: Magnolia Pictures.

Grey, C. (2009). A very short, fairly interesting and reasonably cheap book about studying organizations (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Hoffman, B. J., Woehr, D. J., Maldagen-Youngjohn, R., & Lyons, B. D. (2011). Great man or great myth? A quantitative review of the relationship between individual differences and leader effectiveness. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84, 347-381.

Khurana, R. (2002, September 1). Curse of the superstar CEO. Harvard Business Review, 80(9), 60-66.

Kerr, S. (1975). On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B. Academy of Management Journal, 18(4), 769-783.

Kotter, J. P. (2007). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review (Original work published 1995), 85(1), 96-103.

Mintzberg, H. (2009). Managing. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Mintzberg, H., & Van der Heyden, L. (1999). Organigraphs: Drawing how companies really work. Harvard Business Review, 77(5), 87-94.

Murphy, S. E., & Ensher, E. A. (2008). A qualitative analysis of charismatic leadership in creative teams: The case of television directors. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(3), 335-352.

Oakley E., & Krug, D. (1991). Enlightened Leadership. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Ordonez, L. D., Schweitzer, M. E., Galinsky, A. D., & Bazerman, M. H. (2009, February). Goals gone wild: The systematic side effects of overprescribing goal setting. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(1), 6-16.

Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. (2012). Vocation of the business leader: A reflection

Quinn, R. E., Faerman, S. R., Thompson, M. P., McGrath, M. R., & St. Clair, L. S. (2011). Becoming a master manager: A competing values approach (5th ed.) Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Saporito, B. (2002, February 10). How Fastow helped Enron fall. Time.com

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture. American Psychologist, 45(2), 109-119.

Sims, R. R., & Brinkmann, J. (2003). Enron ethics (or: culture matters more than codes). Journal of Business Ethics, 45, 243–256.

Stein, M., & Pinto, J. (2011). The dark side of groups: A “gang at work” in Enron. Group & Organization Management, 36(6), 692-721. doi: 10.1177/1059601111423533

Swartz, M., & Watkins, S. (2004). Power failure: The inside story of the collapse of Enron. New York: The Crown Publishing Group.

Tourish, D., & Vatcha, N. (2005, November). Charismatic leadership and corporate cultism at Enron: The elimination of dissent, the promotion of conformity and organizational collapse. Leadership, 1(4), 455-480.

Susan Boswell is the Editor of Baltimore Post-Examiner LLC, overseeing both the Baltimore and Los Angeles Post-Examiner websites. A magazine editor and science writer, her career spans association communications, marketing, and government contracting, including service as a former federal employee. Susan enjoys dog sports and spending time with family.

Really good analysis, helped me a lot to understand Enron case