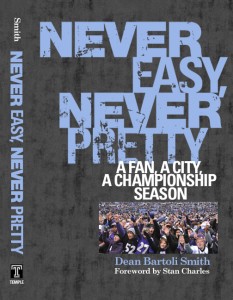

Never Easy, Never Pretty

The Baltimore Post-Examiner is proud to present an excerpt from Dean Bartoli Smith’s book, Never Easy, Never Pretty. You can purchase “Never Easy, Never Pretty” at Amazon.

Amazon Summary: When the Ravens won Super Bowl XLVII in New Orleans, it was a joyous moment for fans and team alike. For Dean Bartoli Smith, a lifelong Baltimore football fan and writer for The Baltimore Brew and Press Box, it was especially sweet. In Never Easy, Never Pretty, he recalls the ups and downs and ultimate thrills of a special season while also showing how a football team impacts its fans and its city. Smith recounts the season from start to glorious finish while interweaving Baltimore’s professional football history, telling his own story of growing up with the Colts, then gradually transferring adult loyalties to the new team in town, the Ravens. Family, friends, and other fans share their recollections, too, letting us see how a football team becomes part of a community.

Smith’s game-by-game recounting of an improbable season brings back all the excitement and uncertainty as the team starts strong, wobbles, then finds its inspiration and character in the playoffs. For each game Never Easy, Never Pretty features a diverse array of quotes, interviews, and commentary from players, broadcasters, and executives, including Joe Flacco, Ray Lewis, Art Donovan, Kevin Byrne, Steve Bisciotti, and Ozzie Newsome.

Never Easy, Never Pretty highlights the Ravens’ electrifying season and celebrates a team, a city, and its emotional landscape during an unlikely run to a Super Bowl victory. The result is an insightful and poignant book about much more than a championship season.

Never Easy, Never Pretty, Introduction

The groom looks confident

like Johnny Unitas among the masses

gathered quickly to witness

another miraculous comeback . . .

underneath the roses in your gloved hands

my unexpected feet kick.

—Dean Bartoli Smith

At 4 a.m. on Sunday, February 3, 2013, I got out of bed and checked the impact of the overnight snow showers. I hadn’t slept much, worried about the San Francisco 49ers offense with a mobile Colin Kaepernick at quarterback and a diverse array of weaponry that would challenge an aging Ravens defense in Super Bowl XLVII . A thin sheet of snow was scattered across Charles Street.

I showered and put on my clean number 82 Torrey Smith jersey. Choosing a Ravens jersey had been challenging. I had spent months trying to decide which player would last the longest in the salary-cap driven NFL and settled on a wide receiver with my last name. The two-week hiatus between the AFC Championship and the Super Bowl had forced me to wash it, which went against my superstitious nature.

Now I was flying to New Orleans to see the game in person. The game tickets and flight cost me $2,000, but my lodging in the suburb of Metairie was going to be free, courtesy of a college friend who loves the Saints. I had scoured every ticket site for days and waited until the last minute, when tickets in the 200 level behind the end zone dropped by $500 on the Thursday before the game.

My six-year-old son had asked several times to go, and I felt guilty for not taking him with me. We had watched the Ravens games together, but this trip was an extravagant expense amid a litany of bills for private tuition, camps, and activities. I kissed my sleeping wife and children goodbye and headed toward the airport

My six-year-old son had asked several times to go, and I felt guilty for not taking him with me. We had watched the Ravens games together, but this trip was an extravagant expense amid a litany of bills for private tuition, camps, and activities. I kissed my sleeping wife and children goodbye and headed toward the airport

At 4:30 a.m. the abandoned streets of Baltimore glistened with moisture. A little more than a month before, the Ravens had been mired in a losing streak and were not a part of any sports talk show discussions evaluating the best teams in the NFL. The last thing on my mind at that point was a trip to the Super Bowl.

Then the Ravens fired their offensive coordinator, announced the retirement of the franchise’s greatest player, and made one of the more dramatic runs in NFL history. As I moved into the left lane for the BWI airport exit, a car full of late-night revelers pulled up next to me, honking their horns, yelling out the window “Go Ravens!” and waving—one final connection to a city that had “gone Raven” and had lost its mind for football. They had seen my trunk magnet and they knew where I was headed.

Once inside the airport, I saw purple jerseys appearing in the corridors: Flaccos, Rices, Ngatas, and Lewises. I felt at home and lucky to be headed for the first time in my life to one of the greatest sporting events in the world. I thought of the Colts fans in my family who loved football and how they had inspired me to make the journey.

My love affair with Baltimore football began at age 7 in the summer of 1970, when my father took me to see the Baltimore Colts practice one afternoon. After breaking training camp at Western Maryland College, they were preparing for the season at the University of Baltimore’s athletic fields off Rogers Avenue, in a neighborhood called Mount Washington. Before that late summer practice, I knew that the New York Jets had shocked the Colts 16–7 in Super Bowl III more than a year before.

The game still perplexed the ladies under the beehive dryers in my Italian grandmother’s basement beauty salon and was fresh on the tongues of my Irish father’s cronies at the Belvedere Tavern.

I listened at the bar over a Shirley Temple.

“Morrall had Jimmy Orr wide open in the end zone,” said my father’s friend Doc Pyle, who carried a pistol in his medical kit.

“I don’t know how he missed him,” said my father. “I heard they had some late nights in Miami Beach.”

My dad had left his sales job at Esso a few weeks before the 1970 Colts had arrived back in town, choosing to follow his passion and become an assistant coach with the University of Baltimore Bees basketball team. He had also recently separated from my mother, whom he had met in Ocean City, Maryland, just seven years before. She had driven her friends to the seaside resort in a royal blue Thunderbird—her prize possession in the summer of 1962.

My father had charmed her with his buzz cut and horn rims. He made her laugh. Before they met, my mother had dreams of becoming a lawyer. Soon enough she learned that a baby was in her near future—me. This discovery put her law career on hold indefinitely and meant selling her beloved car.

On the day after I was born—September 22, 1963—the Colts beat the 49ers 20–14 in Golden Gate Park’s Kezar Stadium. Quarterback Johnny Unitas engineered a 10-point fourth-quarter comeback to give Don Shula his first win as the youngest head coach in the NFL.

My dad had begun following the Colts when the NFL’s Dallas Texans moved to Baltimore in 1953. The original Baltimore Colts had played in the All-America Football Conference from 1947 to 1950 but were disbanded by the league. The ’53 franchise resurrected the Colts nickname that been selected in 1947 in a contest that drew 1,887 suggestions.

My father’s aunt, the late Carita Smith, bought season tickets in 1953, and my dad barely missed a game until 1970. The only exceptions were two “visiting Sundays” at the convent at Mount Saint Agnes College to see his older sister Patricia, a Sister of Mercy.

Aunt Carita worked for the Bendix Corporation making radios, and she carried a flask of peppermint schnapps to the games. She was the sort of fan who in 1960 ripped her brother-in-law Tom Fox’s shirt as they watched Green Bay Packer quarterback Lamar McHan run for a 35-yard touchdown against the Colts on a black-and-white TV.

My Aunt Pat, or Sister MacAuley as she was called, remembers Carita’s visits to the convent. “Carita was a fanatical Colts fan. When I entered the convent in 1956, we could have visitors only once a month. It was always very ‘decorous’ except when Carita was there and there was a Colts game. She had a small transistor radio. I remember her jumping up and screaming either in joy or despair. Not your typical convent parlor scene.”

My father almost missed a game against the Los Angeles Rams in 1968 because Carita had given her extra ticket to Tom Fox, perhaps still making amends for the torn shirt. It was a big game—the Rams were undefeated—and tickets were scarce. My father remembers fans climbing on top of the generators and scaling the fencing to watch from the mezzanine level outside the stadium. He and his friend Dorsey Baldwin snuck into the game. Dorsey’s uncle, a captain in the Baltimore police department, told the boys to meet him at the handicapped entrance. My father threw a blanket over his friend and wheeled him in. Once inside, they waited for the introductions and then ditched the wheelchair, climbing to the top of the stadium to stand in the aisles and watch the game. The Colts won 27–10 en route to a 13–1 season and that fateful trip to the Super Bowl against Joe Namath and the Jets.

In the summer of 1970 I was just a kid entering second grade and was enduring my own streak of bad luck. Joe Namath had beaten the Colts in January 1969. The Baltimore Orioles lost to Tom Seaver and the Mets in the 1969 World Series. The Bullets lost to the Knicks in the playoffs the following spring. And before I went to see the Colts that summer, my parents had gone their separate ways and the Beatles, my favorite band, had broken up.

My dad drove me to the Colts’ preseason practice in his navy blue Chevy Malibu with a crushed back bumper from when he’d backed it into a telephone pole one night. We parked on a hill overlooking the field where you could see all the Colts going through drills. After practice I waited until the players came off the field and asked for their autographs. I got most of the team and all my favorites: Bubba Smith, John Mackey, Ray May, Billy Ray Smith, Rick Volk, Jerry Logan, Tom Matte, Earl Morrall, and Johnny Unitas.

On that day Unitas was the last one to finish. I could see him across the practice field, working with linebacker Mike Curtis, who carried him on his back up a hill that was stepped with wooden planks to serve as bleachers. Unitas then put Curtis on his back and lumbered up the bleacher steps. They finally finished and headed toward me. The sweat had soaked through Mike Curtis’sgray T-shirt. Unitas had on a white shirt.

“Does he want to carry my equipment?” Johnny Unitas asked my dad. I was barely able to move, but somehow I carried his helmet and shoulder pads back to the locker room.

The 1970 season turned out to be a Super Bowl year. My father, my brother, and I watched the Colts play the Dallas Cowboys for the championship at my Uncle Buddy’s house out in the country off Jarrettsville Pike. Down 6–0, Unitas threw a pass over receiver Eddie Hinton’s head. Hinton tipped the ball toward Cowboy cornerback Mel Renfro, who tapped the ball into tight end John Mackey’s hands for a 65-yard touchdown.

The Colts tied the score late in the fourth quarter after a Rick Volk interception took the ball to the Cowboys’ 2-yard line and fullback Tom Nowatzke went in. Rookie Jim O’Brien kicked the winning field goal in a sloppily played game that featured 11 turnovers. “It was the ugliest Super Bowl ever,” said former Colt announcer Vince Bagli.

“O’Brien wasn’t a famous kicker at all. He made a couple of kicks. There were fumbles and tipped passes.”

Former Giants, Eagles, and Rams punter Sean Landeta remembered the kids in his Baltimore neighborhood all wanting to become field goal kickers after O’Brien’s heroics.

“We kicked them through goalposts, over volleyball nets, over clotheslines—anywhere we could after O’Brien won the game. We all wanted to be him.” We were spoiled back then—the Colts, Orioles, and Bullets all had championship caliber teams. We thought it would never end.

In the summer of 1971 my dad left Baltimore to coach basketball with Paul Baker at Wheeling College in West Virginia. He took me out back at my grandmother’s house in Northwood, and we played catch with his football—“The Duke.” He told me he was leaving to pursue his coaching dream. “There’s a kid in my class whose father moved away,” I said. “He doesn’t see him very much.”

“I wish I could take you with me. This is my dream, son. I need to pursue it. Someday you’ll understand.”

With Dad gone, I started playing catch with my Aunt Carol, his younger sister, a Sister of Mercy like my Aunt Pat. I had two auntswho were nuns and a father who was a sports fanatic. Aunt Carol was also a tomboy. She threw long bombs to me on Saturday afternoons at the Mercy convalescent home off of Bellona Avenue. She taught me how to run square outs and post patterns. She bought me the greatest present of my youth, a pair of Rawlings shoulder pads. I would come home from school and put on my football uniform with full pads, including the number 19 John Unitas jersey from Hutzler’s department store.

During pick-up games our neighbor Mr. Seible played on my team. I had a pretty bad temper in the days after my father left and called Mr. Seible a “bastard” just because I didn’t catch a pass he threw to me. I was getting ready to begin third grade and we lived in Courthouse Square Apartments in Towson.

Chuck Seible had been a marine in Vietnam, and he kept the head of a rattlesnake in a jar on his dresser. After my outburst he walked off the field and went home. But before he left he told me to tell my mother what had happened and then come to his house after dinner and apologize to him.

If I didn’t, he would tell her himself. I can still see the doorbell of the apartment; it took me several minutes to drum up the courage to ring it. I sat down in an empty chair next to his as he was finishing dinner. Mrs. Seible was in the kitchen, and little baby Amy was in her high chair. A white tablecloth covered the table.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Seible, . . . for what I said.”

“You need to help out your mom and your brother. You can’t be getting angry and saying bad words over a pick-up football game.”

I understood what he was saying, but during that time, with my father gone, winning and losing meant everything to me.

When the Colts lost, it reinforced his absence; when I lost I just got mad. My brother Brendan and I played football everywhere—on tennis courts, in parking lots, on a grass plot that bordered an alley in Northwood where my grandmother lived. I chipped my four upper teeth when Tolly Nicklas tackled me on a field next to a golf course we played on.

If there was no one to play a full game with, my brother and I played one-on-one football. For most of the fall season in Baltimore, football was on our minds all the time. If we weren’t playing or watching a game, we played table football with a matchbook. I sketched Colts helmets, players, and football fields with goalposts in my notebooks and on book covers.

During class I would scribble all over the “field” and draw lines through the intersecting points that wove their way toward the end zone as the teacher lectured. Football was ingrained in my imagination.

My brother and I spent weekends with my father’s mother. Queenie Smith watched football with us while we ate her signature Irish spaghetti—pasta with meat sauce. “That Johnny Unitas led more comebacks than Carters has liver pills,” she would say.

It was at my grandmother’s that I became mesmerized by The NFL Game of the Week, which featured John Facenda’s famous “voiceof God” and the slow-motion depiction of the game itself. I remember one sequence when the camera focused on a Terry Bradshaw pass and the slow spin of the ball in solitary flight toward its target—a game both brutal and elegant in the same moment.

We also watched football games with our Italian grandparents on my mother’s side of the family, Dino and Carolyn Bartoli. Carolyn, or “Nana” as we used to call her, would get so nervous listening to Johnny Unitas lead a late-game comeback that she would hide under the beehive dryers in her basement beauty shop screaming,

“Oh Dino, I can’t stand it anymore. The suspense is too much. I can’t bear it.” Or she would go to her bedroom and pray the rosary until the game was over.

They loved Gino Marchetti and Alan Ameche and always talked about them. They were so proud that Italian Americans were good at football, and my grandmother loved watching Marchetti make a tackle.

“I loved those rugged old guys,” Nana would tell me decades later, with her mind beginning to fail, “Marchetti, Ameche, and Unitas.”

On most Sundays when the Colts were in town she also prepared her legendary crab cakes and homemade gnocchi with “gravy” (spaghetti sauce) for her brother Bernard Ciampi and her cousin Leonard Cerullo, who would drive down from Berwick, Pennsylvania, to watch the Colts games.

Stories about “Cousin Lenny” permeated my childhood. My mother swore that he could walk onto the field at Memorial Stadium untouched and sit on the Colts bench next to the players.

“No one ever figured out how he got there, and he never told anyone where he was going,” my mother said. He sometimes traveled with bodyguards who wore overcoats and fedoras. He owned a company that made ribbon and fabric, and he provided our family with a lifetime supply of both.

Soon after their separation, my mother and father started dating other people. One day Mom informed my brother and me that we would be going out to dinner with a Baltimore Colt named John Andrews. I’m not sure when or how she met him; at the time she was earning her degree at Morgan State College and working at Ordell Braase’s Flaming Pit as a waitress.

Braase had played defensive end for the Colts until 1968, and “The Pit” was often filled with current and former players. Besides that, many of the players lived among us. They shopped at the same grocery stores and their children played against us on sports teams. As a kid I must have met backup quarterback Earl Morrall five times.

John Andrews played running back and tight end for the Colts. My brother and I were very excited. On their first and only date with Brendan and me along, Andrews took us to Johnny Unitas’s Golden Arm restaurant. It was a great place to go as a kid because all the helmets from the NFL were displayed on the walls and players like Bubba Smith and John Mackey often came there. And the restaurant served something for dessert called a “snowball” that included coconut shavings and warm chocolate syrup over vanilla ice cream.

This was the first time my brother and I had ever had dinner with an African American person. My mother looked like Cher, beautiful with her long and wild Italian black hair. Andrews wore a metallic grayish blue shirt that was open at the collar. My mother remembers that the dining room hushed when we walked in. She felt that all eyes were on her. This was Baltimore four years removed from the race riots of 1968.

The waitress became flustered at one point and dropped a stack of plates next to our table. Johnny Unitas stopped by and autographed pictures for my brother and me. He looked relaxed and enjoyed talking to people in the restaurant.

Johnny liked John Andrews and patted him on the shoulder. The night was going very well until my brother decided to tell a joke. He was only 6 years old and I knew what was coming. He had only one or two jokes in his entire canon. I kicked him under the table and tried to stop him several times, but my mother intervened.

“Your brother is allowed to tell a joke,” she said. “Now be quiet.”

“Mom, you’re going to be sorry,” I tried to tell her.

“Dean, let your brother have his time with Mr. Andrews.”

“What did Abraham Lincoln say when he saw the first black man?” He looked at John Andrews for approval.

“What did he say, Brendan?” My mother asked with a worried

“Bless my heart, bless my soul, I see a. . . .”

“That’s enough!” hushed my mother, finally grasping the situation.

She put her hand around my brother’s mouth before he could finish the punch line and led him into the ladies’ room for a discussion. This was her worst nightmare.

“Sorry about that,” I said to Mr. Andrews. The joke had made its way to the bus stops and halls of Padonia Elementary, where we both went to school. This was my first encounter with racism. The fact that John

Andrews and Johnny Unitas had different colors of skin made no difference on Sundays at Memorial Stadium. Only the touchdowns and the field goals mattered. But a white woman dining with a black man—no matter who they were—was still taboo in Baltimore.

“It’s okay,” he said and smiled. The night had been ruined. I had visions of going to a Colts game, of playing catch with John Andrews. I just wanted to talk football with someone. But that was the last time my brother and I saw him. My mother dated him a few more times without us.

“He wanted to be a part of our lives,” she said, “He was crazy about you and your brother and he was a very nice man. But I had just met Larry.” Mom met Larry, her husband to this day, at the Tom Jones nightclub in Towson. He was quiet, humble, and laconic—a hardworking Johnny Unitas type. She helped Larry study for a law degree and at 46 realized her own dream of becoming a lawyer.

My dad returned from Wheeling College in 1976 and got a job coaching the Johns Hopkins basketball team. He lived in the Guilford Manor apartments across from Homewood Field at Hopkins, where on Sunday mornings the medical students would play a pick-up game of touch football in their scrubs. I often went down to the field, which was also deep centerfield of the baseball diamond, and played on one of the teams as an extra rusher. I’d count my four “Mississippis” and rush the passer.

The Colts were just starting to get good again. They had a young and dynamic quarterback from LSU named Bert Jones. He threw bombs to Roger Carr and Raymond Chester, and on third downs his favorite target was Don McCauley. Lydell Mitchell was a hard-nosed halfback who could catch the ball as well. The organization had cleaned house after Johnny Unitas left and the new players were beginning to gel. The defense was also getting better after a 4–10 season in 1973 and a 2–12 campaign in 1974. In those losing years, most Colts home games did not sell out, and that meant they were not on television. Our lives hung on the crisp and poignant radio voices of Chuck Thompson and Vince Bagli. Thompson’s voice, born from the concrete and splintered bleachers of Thirty-Third Street, transformed the exploits of the blue and white gladiators into legend.

“Good afternoon everybody,” he would boom from the transistor, and from that point on he was everybody’s father. “When the ball was in motion, nobody described it better than Chuck,” said Bagli. “We were a bunch of ‘rinky-dinks’ compared to him.”

I witnessed two painful playoff defeats in Memorial Stadium. On December 19, 1976, my father took my brother and me to watch the AFC Divisional playoffs against the Steelers. The Colts had a rising star in Bert Jones and a defensive line called the Sack Pack, but their secondary was suspect. We sat in Uncle Buddy’s seats in the horseshoe behind what was home plate during the baseball season. On the second play from scrimmage, Colts defensive lineman Joe Ehrmann broke through and tackled Franco Harris—putting him out of the postseason with an ankle injury.

On the next play, Terry Bradshaw dropped back to pass. My eyes traveled downfield before he threw the ball, and I could see a Steeler receiver down the far sideline alone—the nearest Colts defender 15 yards away. The play resulted in a 79-yard touchdown pass to Frank Lewis. The Colts never recovered and lost 40–14.

Just after the game had ended, a plane flown by the lunatic Donald Kroner crashed into the upper deck. Fans had left early because of the score and no one was hurt.

The next year, on Christmas Eve, I went with my Uncle Bernie to see the Oakland Raiders play the Colts in the playoffs. Carolyn Bartoli made us meatball subs and wrapped them in tinfoil. Kenny “The Snake” Stabler played quarterback for the Raiders that day, and they possessed many potent offensive weapons. It was an exciting back-and-forth contest—one of the greatest games in NFL history—but the Colts let it slip away.

We had the ball in the fourth quarter with a lead and a little over five minutes remaining. Instead of trying to get the first down, coach Ted Marchibroda—nicknamed “Furrowed Brow” by my Dad—called three straight running plays and had to punt the ball back to Oakland.

With 1:44 remaining and the Colts in the lead 31–28, Stabler dropped back to pass and threw a deep and lofting spiral to his tight end Dave Casper on a post route. As Casper went into the cut to the post, he looked back and saw the ball headed in the opposite direction over his right shoulder. He changed course in a writhing motion like a second baseman trying to flag down a pop-up being carried by the wind and somehow brought in the ball at the Colts’ 14.

The Snake had reduced us to defenseless mice. That play, “The Ghost to the Post,” allowed the Raiders to tie the game and eventually win in overtime, 37–31. My Uncle Bernie and I drove back to my grandmother’s house in Parkville for our annual Christmas Eve celebration that included Nana’s pasta and meatballs along with the turkey and stuffing.

It was my last Colts game. On the lot next to the house were the remaining rows of lonely Christmas trees left on a cold night. I went outside with a football and weaved my way through the trees on the lot like I was Lydell Mitchell scoring the game-winning touchdown against the Raiders. I spent a large part of my childhood changing the outcomes of Colts losses in my mind.

My brother and I moved from Baltimore to the suburbs of Chicago in 1979 to live with my mother and stepfather. Larry had been given an ultimatum from his company to take a promotion and relocate or never advance. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do.

My father stayed behind in Baltimore, along with the rest of my heroes—Unitas, Mackey, Mitchell, Jones, and Curtis. Our last dinner together was at the Flaming Pit, where my mother used to work. Dad gave me a blue blazer for my sixteenth birthday. My father was in tears and I could barely look at him. It was more gut wrenching than when he had left for Wheeling. We took off for Chicago the next morning. The Colts never returned to the playoffs, and five years later owner Robert Irsay moved the team to Indianapolis.

In my third year of college at the University of Virginia, I watched the devastating scene that ensued in Owings Mills as the snows came down and the Mayflower vans filled with all the Colts equipment, along with my childhood memories, departed. One of my mother’s friends on the North Shore of Chicago knew the Irsay family, and we got into a heated discussion about the Colts. Her name was Carry Buck, and her husband John was described to me by my mother as the Donald Trump of Chicago.

His first job out of Notre Dame was to lease all the space in the Sears Tower. Mrs. Buck taught me my first lesson in business.

“It’s his team, he can do what he wants with it,” she said.

“I hate his guts,” I said.

“That doesn’t matter to him.”

Soon thereafter, I also sold out to the Irsays. Carrie got me a job working for the Robert Irsay Heating and Cooling Company in Skokie, Illinois. It was a sweatshop filled with mastodon-like welders and tinners who spoke only in expletives, and I completed an assortment of odd jobs, including cleaning out trailers, many of which had Baltimore Colts stickers on them.

Football in Chicago was also a way of life, though the Bears weren’t very good back then. Walter Payton was the star running back, and it seemed like he carried the ball on every play. Sometimes he even played quarterback. But compared to the glory days of the Baltimore Colts, the Bears were lumbering through their dark ages.

In truth, after the Colts left Baltimore, I lived in NFL exile for the next 12 years, only briefly adopting the Giants while living in Manhattan because I had played on punter Sean Landeta’s basketball travel team when I was 10 years old. I could also justify being a Giants fan because their general manager George Young was also a Baltimorean. But I longed for the NFL to return to Baltimore and knew in my heart that I had no team.

When the Ravens arrived in Baltimore in 1996 from Cleveland, I was happy my city had a team but I didn’t like the way it happened. I had attended graduate school in New York with novelist Michael Jaffe, a Browns fan who had frequented the Dawg Pound in Municipal Stadium. His passion for Cleveland matched any fan’s passion for the Baltimore Colts. My city had sold our collective soul to get a team just the way Indianapolis had hijacked the Colts. It was hard to give them my heart.

My first Ravens game was against the Indianapolis Colts in 1998. Jim Harbaugh played quarterback for the Ravens, and it was Peyton Manning’s rookie season. Ravens Stadium reminded me of those Coleco electronic football games with the vibrating fields that made the players move. There was no baseball diamond or dirt bowl like the old Memorial Stadium. The “Big Wheel” and the “Spoke” who ruled the upper deck at Colts games with their “C-O-L-T-S” cheer were also gone. The sidelines were narrow, making the field the main event.

I didn’t know these people in the stands wearing purple jerseys with names like Boulware and Lewis. I didn’t even know which team to root for, so I settled on cheering for the Ravens’ Jim Harbaugh, whom I’d seen play for the Bears. The Colts had died inside me. Manning and Harbaugh dueled all afternoon, with the Ravens prevailing, 38–31. It was the last time Peyton Manning lost in Baltimore as a Colt.

More than 30 years after holding her ears and running into her beauty shop during another Johnny Unitas comeback, Carolyn Bartoli attended her first Ravens game at the new stadium. The Ravens played the Vikings, and a lot of Minnesota fans in our section were dressed in helmets and shields, like Norse warriors.

My friend Wayne Brokke, a Baltimore restaurant owner, had gotten the tickets and was attending his first football game. My grandmother fixed him with a Neapolitan eye and instructed him to “boo” whenever the Norse folk cheered for the Vikings and to cheer whenever they “booed.”

At the age of 83, she witnessed three kickoff runbacks for touchdowns in the first quarter of the game, including two by the Ravens. Baltimore lost that game, but she talked about it for days. Nana made her delicacies on Sundays, and we watched the Ravens games at her home in Pasadena just as her brother and cousin had in the 1960s. Nana loved having football parties and turned the sound down so we could listen to Dean Martin’s greatest hits like “You’re Nobody till Somebody Loves You.” Dino Bartoli still talked about Ameche and Marchetti.

I started taking an interest in the Ravens during the 2000 season. Ray Lewis had been charged with double murder in Atlanta the year before, and when he returned to the team after being acquitted he said he desperately needed to get to the Super Bowl. During that year’s playoffs, I watched from a hotel pool in Arizona as the Ravens played the Tennessee Titans. Tennessee had just missed winning the Super Bowl the year before by a couple of yards, but Baltimore was staying close to them in this game. Then Ray Lewis hit Titan running back Eddie George just as the ball arrived from quarterback Steve McNair. The Ravens’ linebacker stole the ball and ran 50 yards for a touchdown. Game effectively over. The next week Trent Dilfer found Shannon Sharpe on a slant pattern for a 92-yard touchdown against the Raiders. Tony Siragusa flattened Oakland quarterback Rich Gannon, and the Ravens were headed to Tampa for the Super Bowl. I watched the Ravens win the 2000 Super Bowl with my uncle, and we drove downtown after the game. People crowded the roads into the city. In Fells Point, fans climbed on street signs. I was happy for the city but I still didn’t know these people.

A few months later I went to see The Producers on Broadway, starring Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick. On the way to my seat, I saw Ravens owner Art Modell with Giants owner Wellington Mara, not quite the Leo Bloom and Max Bialystock of the NFL. I went up to Mr. Modell and introduced myself.

“Thank you for bringing football back to Baltimore,” I said. “My family members in Baltimore thank you.”

“You’re welcome,” he said. “My pleasure.”

I arrived at the Atlanta airport to discover that my connecting flight to New Orleans was delayed by an hour. The football gods were having a field day with me this Super Bowl Sunday. In the boarding area Ravens fans mixed with 49ers fans wearing Davis, Kaepernick, Gore, and Willis jerseys. Finally we took off and arrived in New Orleans shortly before 1:00 p.m.

The atmosphere on Bourbon Street included packs of Ravens and 49ers fans. The Ravens mob drowned out the Niners faithful with Jack White’s “Seven Nation Army” anthem. Niners fans struck back with Jim Harbaugh’s popular refrain taken from his dad, “Who’s got it better than us. No . . . body!” It was football paradise. I never expected to be strolling down Bourbon Street waiting for my home team to play in the Super Bowl. I saw someone in full Johnny Unitas uniform—pads, jersey, high-top cleats. I thought about my son who had desperately wanted to go.

He had recently played football for the first time in his life and was beginning to feel the pull of the game. He and I had fallen in love with these Ravens together. I had moved my wife and two kids back to my hometown of Baltimore in August 2010 for a job at the Johns Hopkins University Press. Shortly thereafter I scoured the classifieds for season tickets to the Ravens.

I was struck by how passionate the city was for this team. It seemed that nearly everyone had exchanged Colts jerseys for Ravens garb. Game jerseys appeared everywhere around town on Purple Fridays. Season tickets secured, we found a house close to my office at Hopkins. The stone mansion once occupied by the poet Ogden Nash, who immortalized the Colts in verse for a 1968 Life magazine article, stood just around the corner. My father had attended parties in the house next door to ours. That’s Baltimore, or “Smalltimore” as it is called by the locals—a place where everyone is connected in some way.

At one time that house next door had belonged to the Fusting family, and my dad had gone to Loyola High School with Bill. In the late ’50s, my house hadn’t been built, and the lot was a long and flat rectangular patch where the Fusting boys played tackle football. I’ve described the scene in my poem “Trash Night”:

“The No. 11 bus to Canton rounds the corner like Jim Parker, and gone are the days of the Fusting boys playing tackle on an empty lotdisguised as Unitas, Berry and Moore.”

My 4-year-old son Quinn and I attended the first home game of the Ravens’ 2010 season against the Cleveland Browns. The deafening sound in that stadium when the defense took the field made my son hold his ears. It’s a roar that comes from the depths of the blast furnaces at Sparrow’s Point, from the lathes and the printing presses and the abandoned locomotives parked just a few blocks away. Our seats are at the back of the end zone along Russell Street, where you can look out and see the roundhouse of the B&O train station and Pigtown to the west, the place where the stories from the television show The Wire unfold in real life every day. The intimate concrete bowl of the stadium fills with the agitated timbre of football fans chasing pigskin exploits from neighborhood to neighborhood—from Patterson Park to Homewood Field to the disenfranchised gridiron ghosts wandering Thirty-Third Street in search of Memorial Stadium.

It’s the sound of Mobtown—with its roots in the Pratt Street riots at the onset of the Civil War and in the Battle of 1814, when the citizen-soldiers of the city repelled fleets of redcoats. My son and I became part of that tradition, but even so I still wasn’t quite hooked.

On September 11, 2011, the Ravens opened at home against the Steelers, and I went with my father. I remembered that receiver Anquan Boldin had dropped a pass at the goal line in the last few minutes in Pittsburgh, a play that helped end the Ravens’ 2010 season. It was the tenth anniversary of the World Trade Center tragedy and the ninth anniversary of Johnny Unitas’s passing away.

My father and I walked down Martin Luther King Boulevard toward the stadium. He had once told me, “I’m a fan as long as they don’t embarrass the city.” We both wore Ravens jerseys; it was the first game with the new franchise that we had ever attended together. The Ravens demolished the Steelers 35–7. Ray Rice took the first snap and blasted through the hole for 36 yards into Pittsburgh territory. Two plays later, Boldin snared a 27-yard touchdown pass. And then something strange happened. The referee raised his arms and mistakenly announced, “Baltimore Colts touchdown!” It was an unintentional nod to Unitas and all the former Baltimore Colts who had embraced the Ravens, old friends like Lenny Moore and Bruce Laird.

I looked at my dad in his Ray Lewis jersey and thought of his 60 years of following football in Baltimore. In that moment I became a Ravens fan. In the fall of 2012, I coached my daughter Julia’s grade school soccer team. We played our home games on that field off Rogers Avenue where the Colts had practiced on a late August day in 1970. It’s now called Northwest Park, and I often wondered if I was the only one who had experienced its storied past. I may have been the only parent who knew that the barn-like gymnasium on the side of the hill was once called the Bees’ Nest.

During the games, I would turn around and look at those wooden plank bleachers, overgrown with grass. In my mind I saw Mike Curtis carry John Unitas on his shoulders up the steps one more time. I’ve spent my life running under a Unitas touchdown pass.

Born and raised in Baltimore, Dean Bartoli Smith is the author of NEVER EASY, NEVER PRETTY: A Fan. A City. A Championship Season (Temple University Press, 2013) and a contributor to the 2nd Edition of Ted Patterson’s FOOTBALL IN BALTIMORE (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).

He attended Loyola High School and graduated from Loyola Academy in Wilmette, Illinois. He majored in English at the University of Virginia and received an MFA in Poetry from Columbia University. He is director of Project MUSE at The Johns Hopkins University, a leading provider of digital humanities and social science content for the scholarly community.

His poetry has appeared in Poetry East, Open City, Beltway, The Pearl, The Charlotte Review, Gulf Stream, and upstreet among others. His book of poems, American Boy, won the 2000 Washington Writer’s Prize and was also awarded the Maryland Prize for Literature in 2001 for the best book published by a Maryland writer over the past three years.

He writes sports for Press Box and Baltimore Brew.