Missing the Point: Lowering property tax rates will not save the city of Baltimore. Not even close!

A couple of weeks ago, The Baltimore Sun ran an editorial about Maryland’s need to grow its population. The primary point of the editorial was that Baltimore is continuing to lose its population, which is understandable. That said, growth has got to be environmentally friendly. That’s true, but the piece lacked “importance.” I read it and, in my head, heard the immortal words of George Costanza, “Yada, yada, yada.”

What’s bothering me about the Sun editorial? It’s that Baltimore is not having an environmental crisis, certainly not any more so than any other place on the planet. There’s no argument that the rebirth of a great city can and must be accomplished in an environmentally friendly way. But that goes without saying. So why is the Sun talking about it like it’s a profound objective of recovery?

Turns out, I wasn’t the only one disappointed by the Sun’s editorial. Just the other day, Steve Walters who is with the Maryland Public Policy Institute responded with his own comment, “Best fix for the shrinking city is a tax cut.” I don’t know Mr. Walters. Never had the pleasure of meeting him. He’s right that the Sun’s editorial lacks the urgency that is essential for stopping and then eventually reversing the city’s continuing decline. Suffice it to say that I agree emphatically with pretty much everything he says – except the specific pro-growth solution he offers.

As what I’m sure was meant to be only one element of a more comprehensive recovery plan, Mr. Walters points out that the city’s property tax rate is way too high and needs to be competitive with nearby jurisdictions. Lowering the rate will stabilize the city’s population and “attract a flood of investments.” …Really? I don’t think so.

For the purposes of this piece, the primary objective is to stop and then reverse the net negative outflow of people from the city. Baltimore’s population has fallen from a 1950 high of 949,708 to an estimated 2023 population of only 575,133 – down by 7.38% since 2010 in just the last twelve years.

Who, exactly, are all these people leaving Baltimore? Could it be that the moniker “Charm City” is only wishful thinking? Some survey research would be very helpful here, but in the meantime let me venture a guess. The people leaving are those who can find better jobs in nicer, safer places to live. It’s just that simple. Property taxes, in and of themselves, are just not a major determinant of residential interest in a community. Time to illustrate my point.

By the way, we’re talking about residential decision-making, but commercial and industrial location decisions, to the extent that they involve property taxes, are not dissimilar.

“Uh, oh. You’re going to show us data, aren’t you?”

Yes, but come on, cut me some slack. The people and city of Baltimore are well worth the extra effort.

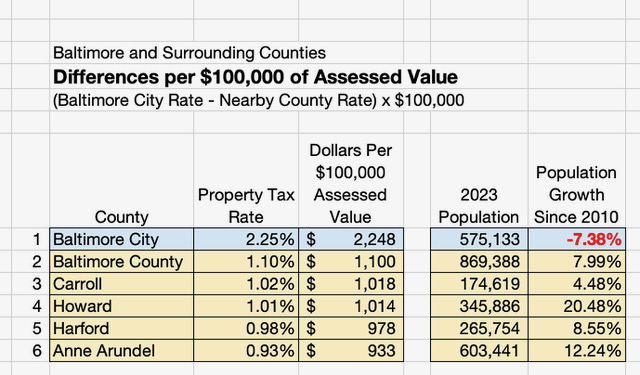

Let’s start by looking at the top section of the table below. On six lines it shows the property tax rates for Baltimore City and the five nearest counties around it.

Even people working in the city – including police, firefighters, and teachers – do, in fact, choose sometimes to live elsewhere, within a convenient commuting radius, but someplace other than Baltimore. By that standard, these are the five counties with which Baltimore City property tax rates would need to be competitive.

Notice that all five surrounding counties have experienced positive net growth since 2010. Only Baltimore’s population has declined.

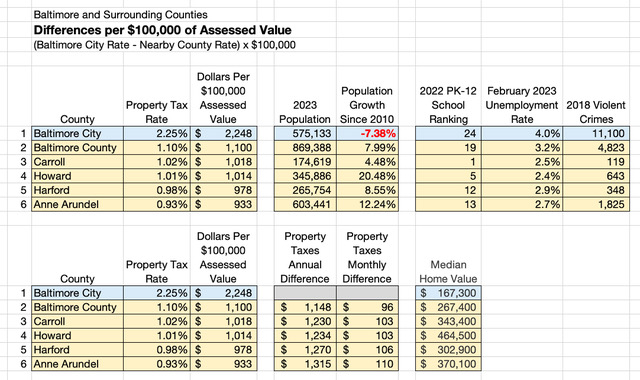

In the lower section of the table, you can see the difference Baltimore’s higher property tax rates make on an annual and monthly basis per $100,000 of assessed value. Round numbers, the difference between property taxes calculated at Baltimore’s 2.25% rate versus the much lower 1.00% or less in the surrounding counties is $100 per month per $100,000 of assessed value. That’s $300 more, for example, every month if you live in a $300,000 house. See the column labeled “Median Home Value.”

Even if you rent your house or apartment, you’re paying property taxes in the monthly payment you make to your landlord.

No question about it, that’s a lot of money, particularly for middle and lower-income families.

“Geez. No wonder people are leaving the city!”

No. The real estate taxes they’re paying are significant, but that’s not why they’ve decided to move. For most people, while property tax rates in suburban counties are lower, the cost of housing in the suburbs is significantly higher. And those higher costs of housing mitigate against the savings from lower property tax rates.

Once again, look at the column labeled “Median Home Value.” People aren’t leaving the city to save money on the cost of housing – although many families will get more and better housing for their money in the suburbs. They’re leaving for the advantages of living in the suburbs having to do with the quality of housing, superior shopping, better schools, and safer neighborhoods – and for the higher paying and broader spectrum of jobs that growth creates.

Look back at the top portion of the table above. Baltimore has the highest property tax rates, but is ranked last (24th) in the state when it comes to public education. Not incidentally, public education is funded largely by property taxes. Lowering property tax revenues isn’t going to improve the quality of the public schools Baltimore’s children attend.

In the next column to the right… Unemployment in the city, currently at 4.0%, is substantially higher than in the surrounding counties where the job markets are hotter and more diverse. And that 4.0% rate is citywide. Un- and under-employment rates in the lower-income sections of the city are undoubtedly much higher.

And do you really want to talk about crime in Baltimore, in total or on a per capita basis, compared to the surrounding counties?

Lowering the city’s property tax rate isn’t going to stop the outflow – and it certainly isn’t going to encourage net positive migration to Baltimore. Ask yourself the following question, “How much lower would property taxes need to be in Baltimore to get you to stay in the city or move there?”

Is there an amount coming to mind or are you saying to yourself, “I’m not moving to Baltimore City, period!” Maybe if all other factors were equal, but they’re not, are they? The differences were talking about are profound. It may be an extreme example, but it makes my point… In Howard County, downtown Columbia’s development is going to be anchored by a world-class public library. In Baltimore, the downtown is anchored by a struggling casino and now a Top Golf driving range and bar. Surrounded by streets where personal safety is problematic, to put it nicely. If you can afford to leave Baltimore – either because you’ve found a better job in the suburbs or plan to reverse commute to your job in the city – where would you rather raise your children?

If you want to play with changes in property tax rates to stabilize the city, consider varying the rates depending on personal income and company revenues. Property taxes tend to be “regressive” in the sense that lower-income families pay the same rates as higher-income families who can more easily afford the burden. It doesn’t have to be that way.

Do you want people to stay and eventually choose Baltimore as a bona fide residential and investment destination? And achieve that objective quickly? While you take the time to improve education, lower crime rates, and effect other long-term enhancements to life in the city? Well then, leave the city’s property tax rates where they are and use Baltimore’s vast inventory of vacant properties to the city’s advantage. Give those properties to carefully selected, environmentally friendly companies offering on-the-job training for the city’s un- and under-employed. Create the jobs that raise household incomes for the two-thirds of the city that is struggling to get by – and then watch the good stuff that happens next as the people of Baltimore, by themselves, organically, stabilize and eventually re-ignite the growth of the city’s economy and population.

Les Cohen is a long-term Marylander, having grown up in Annapolis. Professionally, he writes and edits materials for business and political clients from his base of operations in Columbia, Maryland. He has a Ph.D. in Urban and Regional Economics. Leave a comment or feel free to send him an email to [email protected].