Legacy of my deaf ‘bachelor’ uncle

The Coyles gather for ice cream on vacation in Maine, Aug. 26, 2012.

“He was a player,” my cousin, Kim said. We laughed. It felt better. My Uncle Al, her father, had died in his sleep that morning. My uncle was my father’s kid brother. They are both gone now within a year.

Kim called me the day after I returned from an eight-hour trip over the Tappan Zee Bridge and the Garden State and New Jersey parkways.

We had all just enjoyed a family vacation at Higgins Beach in Maine. Uncle Al had difficulty navigating the beach’s worn, wooden steps that descended from the sand filled sidewalk. He gripped the flat, salt worn wood of the handrail and grunted with each step.

We were used to his grunts. My uncle was deaf. He spoke in a combination of sign language and a voice that was difficult to understand. He read lips. Uncle Al was a graduate of the Halifax School for the Deaf in Nova Scotia.

I knew him long before my cousin was born in 1971; the year I graduated from high school.

I would sit in his lap with the Sunday funny papers when I was too small to read. Studying the drawings with the balloon of words over each cartoon’s head, I’d try to understand what Uncle Al was reading to me. His words were incomprehensible, but I didn’t mind.

He was funny.

In the car heading toward Maine, we talked about golf. I said, BORING clearly and carefully so he could read my lips.

When I mentioned that I wanted to visit Andrew Wyeth’s Farnsworth Art Museum, he shook his head, “BORING!”

We had several breath-taking days of late summer weather at the beach. We ate lobster, clams, onion rings, ice cream. Uncle Al drank a bit of the whiskey he loved and did all the impressions for which he was famous — John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, James Cagney. As a child, Uncle Al spent much time in the movie theater, studying the actors’ mannerisms. He could walk with a swagger and roll his head calling us, “Pilgrim.”

On our first night at the beach, I sat at the dining table with Kim, her two brothers, Charlie and Craig, their spouses, and Uncle Al. Running loudly through the house – though he could not hear them – were his six grandchildren. I swept an arm at the 14 of us sharing the beach house, “I used to think that Uncle Al would be my bachelor uncle.”

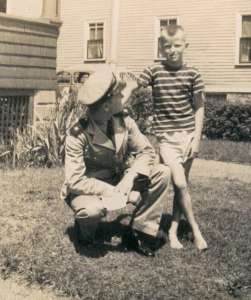

My cousin, Kim sent me a photo of my father and hers the day after my uncle died. In it, Uncle Al must be 11 or 12, because my father is in his U.S. Marine Corps uniform; dark epaulets on his shoulder with a white star, a cap with a shiny black visor and lace-up shoes that look polished. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor the same year my dad graduated from high school.

In the photo, my uncle has his hand on my dad’s shoulder. Uncle Al is barefoot, wears light colored shorts and a striped t-shirt. His hair is short and he stares out at the camera.

My dad is crouched, and he looks up at my uncle. He was 8 years older than his brother and the photo made me cry. I had never seen it before.

The night before my uncle’s wake, my cousin Bruce took Kim and me to dinner on a green tree-shaded street in Melrose. Bruce is the son of my father’s and Uncle Al’s only sister, Bette, who died in June. All three siblings are gone now, within a year. But we did not shed tears. We enjoyed stories and the best one was about Uncle Al.

Two weeks before, Bruce and his wife, Sandra, had driven him to see his old house on President’s Street in Lynn, and to lunch at his favorite restaurant, Denny’s. When they took him back to the New England Home for the Deaf, Uncle Al told Bruce and Sandra that he was tired, that he wanted to take a nap. They kissed him good-bye.

But before they left, Bruce and Sandra stopped to talk with someone they recognized. Ten minutes passed. Sandra spied Uncle Al rolling his walker at a fast clip, his head down. When he looked up and saw them, a “sheepish” grin spread on his face. I could imagine it. Uncle Al had a space between his two front teeth.

Sandra added that she could see two women through a glass window, in a sitting room waving at Uncle Al, lip-syncing, “C’mon!” They pointed to an empty chair between them.

My “bachelor” uncle married Kim, Charlie and Craig ‘s mother, Gail Bradshaw, when he was 40 years old. He was widowed for almost five years, and lived an exemplary life in spite of — or perhaps because of — his deafness. I know of no other senior citizen with a bigger network of friends. The deaf community is wide and active. He appeared to enjoy the New England Home for the Deaf with many of the people with whom he skied, danced, traveled and watched sporting events for over seven decades.

His death was a shock. In one of our last photographs, I have my arms around his shoulders. We are smiling in the sun at Higgins Beach and the small gap between his front teeth is clearly visible.

I hugged him good-bye when our vacation was over. Then I crossed my fisted hands over my heart, “I love you.” He sat on the edge of his bed, his luggage beside him. Uncle Al got up to walk me out.

But I wonder if he was actually searching for the women who saved him a seat between them.

Caryn Coyle writes about arts, culture and food for the websites CBS Baltimore and Welcome to Baltimore, Hon. Her fiction has been published in a dozen literary journals including Gargoyle, JMWW, The Little Patuxent Review, Loch Raven Review, Midway Journal, The Journal (Santa Fe) and the anthology City Sages: Baltimore from City Lit Press. She won the 2009 Maryland Writers Association Short Fiction Award, third prize in the first Delmarva Review Short Story Contest, 2011 and honorable mentions for her fiction from the Missouri Writer’s Guild (2011) and the St. Louis Writer’s Guild (2012).

Beautifully written about Allison. We had been good friends for over 50 years. Gail and my wife, Helene grew up together at Clarke School, thus we got together frequently. Yesterday, after the Patriots-Titans game, I thought of calling him about the game and realized that he was not with us. We miss him.

Mel Wheeler

Thank you, Mel It was good to see you last week, and a comfort to know how much you loved Uncle Al, too.