A Civil War Christmas: Bomb hits Baltimore in baleful Centerstage production

At the point the guns fell silent on Christmas Eve 1864, 657,991 Union and 558,207 Confederate soldiers were counted as casualties of the American Civil War. Thousands more would die from horrific wounds, starvation and disease before the carnage finally ended the following spring. President Lincoln would also die at the hands of a vengeful assassin. Not exactly an uplifting backdrop for a holiday play, especially if it is a tedious, tasteless romp. But that is precisely what Centerstage is offering with its production of A Civil War Christmas.

Uninspiringly directed by Rebecca Taichman, A Civil War Christmas is the brainchild of Obie Award winner Paula Vogel. The play mixes a mind-numbing series of vignettes with modern takes on time-honored Christmas music; all meant to draw the audience into the lives of a fast-changing cast of characters. Lacking in this mix is an engaging storyline, as more often than not, the playwright opts for caricatures of the famous players and stereotypes of the citizenry and the soldiers. In the process, Vogel denigrates several icons of American History in what can best be described as a quest to wrench a few nervous laughs and hammer home her social agenda.

Case in point was one bit of dialogue between an escaping slave named Hannah and her daughter, Jessa. When Jessa complains about being tired and hungry, Hannah says:

“When we cross the next river, we’re gonna to be in the United States of America. And the president there – it’s his job to feed people who don’t have any food, and to find a roof for people who don’t have a house.”

Never mind that it’s not the President’s job to give anyone a home. I was half expecting this Lincoln to give them cell phones, too.

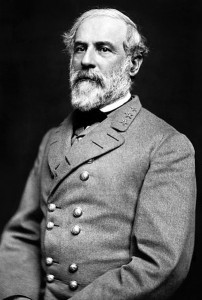

In another scene, Robert E. Lee tells his slave, Willie Mack, that he would not drink captured Yankee coffee, because his men were starving and had none of their own. While this sequence came off as stilted, it was made worse when the actor playing Willie Mack, used this as a chance to mug for the audience before drinking the coffee himself.

Then we have ~

Lee: “We’ve lost.”

Willie Mack: “Yes sir… You have. (Pause) We have.”

Cue the laugh track.

It’s not just the Rebels who come to be the butt of the jokes. General Grant is played as a falling-down drunk to garner cheap laughs. General Sherman and John Wilkes Booth fair none the better. And Lincoln kicks up his heels in a scene reminiscent of The Producers.

One could almost imagine the bedlam of the casting call for this play. “Will the dancing Lincolns wait in the wings? We are only seeing singing Lincolns.”

It appears the playwright aspired to something akin to Les Miserables, but what we have is more like one of those preachy pieces from the days of the Federal Theater Project.

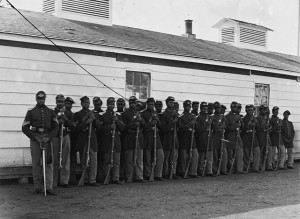

Along with mocking Lincoln, Lee, et al, A Civil War Christmas contains anachronisms and historical errors. Denying the presence of black troops in the Confederate army is one; another (found in the program) is maintaining that Lincoln was the only sitting president to witness a battle. Then there is the writer’s choice of music.

Music permeated life during the Civil War (the song Lorena was actually banned in the South because it made some soldiers homesick). Vogel weaves her tale with her take on a number of time honored tunes. But several of the songs, including Marching Through Georgia (1865), I Heard The Bells (music composed in 1872) and Ding Dong Merrily on High (a traditional French carol which wasn’t translated into English until 1924), were written years after the play’s 1864 setting.

In the program notes, playwright Vogel says she was charged by her late brother Carl to teach history to the children of their family. One shudders to think of what other folderol Vogel may have fed those children.

Adding to the problems with the play were plenty of miscues by the director, Rebecca Taichman. The relationships seem forced, the pacing uneven, and the drama never quite takes in a way which would make Vogel’s work palpable.

For example, we are asked to feel sympathy for Mary Todd when she is reminded of her dead son Willie; and later for her seamstress Mrs. Keckley when, in a flashback, her brother Little Joe is sold by their master. But moments like these need to be earned, not foisted upon an audience. In the end, both tragedies come off as mere contrivances.

Another painful moment was saddling an enthusiastic southern teen (Andrea Goss) together with A.J. Shively as a horse. Goss was more Annie Oakley than a young Confederate, and Shively pranced about the stage like My Friend Flicka; complete with cocoanut shells ala Monty Python.

Cocoanut shells?

Really, Ms. Taichman???

It should also be noted that only one actor (Matthew Greer) bothered to sport a full beard for this production. This was puzzling considering the fact that the era was known for hardy male figures with facial hair. Greer’s beard works fine for his turn as Grant, but a little less so as John Wilkes Booth and not at all when he shows up as Mary Surratt.

A bearded Mary Surratt?

Really, Ms. Taichman???

In his defense, Greer actually did a nice job hanging in there as Mary Surratt, and from all accounts, she was a pretty tough woman.

The questionable direction notwithstanding, I got the sense that the actors were working very hard to put over lines they would just as soon forget. Still, some moments were utterly egregious.

Tyrone Davis, Jr. did way too much mugging, especially as General Lee’s servant Willie Mack, and Sekou Laidlow came onto stage smiling at the audience as the curtain was about to rise. Way to break that fourth wall even before the play begins.

Oberon K.A. Adjepong was a powerful presence as Union soldier Decatur Bronson, but for some reason, we’re not supposed to notice he is blacksmithing by pounding on a modern steel chair.

Tracey Conyer Lee’s Mrs. Keckley was perhaps the strongest character in the play, but there was no real connection between Conyer Lee and Kati Brazda’s crazy Mary Todd Lincoln.

Mathew Greer as Booth/Grant and Jeffry Denman as Lincoln/Lee were solid enough, though it seems the male leads are almost an afterthought in Vogel’s story. If there was one stand out performance it was Sierra Sila Weems as Jessa/Little Joe. The Lutherville Lab Elementary third-grader far out-shined most of the other players, including Nicole Lewis, who portrayed both her mother Hannah and the sanctimonious Rose.

On the production side, Music Director Victor Simonson takes almost every number too loud. Aside from the clanging steel chair and cocoanut shells, there’s really no reason for the excess volume.

The illumination of the stage worked reasonably well, though at one point, Scott Zielinski’s lighting was so harsh, I half expected the cast would confess to a crime.

The most interesting aspect of the production was Dane Laffrey’s set.

Stripped to the bones, the set seemed strangely familiar with its wood plank floor, grand piano and earnest little Christmas tree standing at stage left. That’s when I realized it looked like the set from A Charlie Brown Christmas. It’s a shame that A Civil War Christmas doesn’t have the pathos of a children’s cartoon.

Perhaps a better play would have been to simply have young Jessa recite the Gettysburg Address.

That’s what the Civil War was about, Centerstage.

************************************************************************************

Centerstage’s production of A Civil War Christmas runs now through Dec. 22. Running time is 2 hours and 30 minutes with one intermission. Tickets and other information may be found online.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”

This is the funniest review I think I’ve ever read! Kudos to you, Mr. Hayes, for creating a completely entertaining read while completely missing the intention of the play and the production. You should audition for The Colbert Report.