BMA Exhibit Will Explore Women Printmakers of the WPA

Exhibition features 50 works drawn from the BMA’s extensive holdings of nearly 1,000 prints made by WPA artists

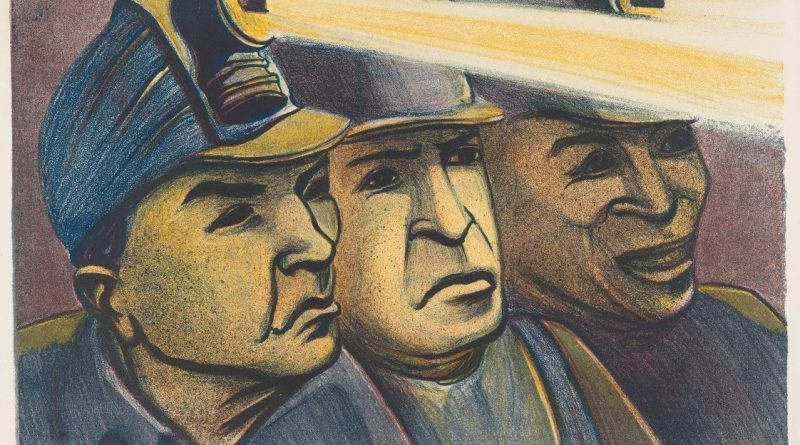

BALTIMORE, MD — In 1935, the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP) began offering employment to millions of workers affected by the Great Depression, including a wide array of artists from across the country. Art/Work: Women Printmakers of the WPA, opening at the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) on November 5, offers new insights into the vast contributions of women printmakers, who gave visual form to the fraught state of American society throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. Featuring approximately 50 works drawn from the BMA’s extensive holdings of nearly 1,000 prints made by WPA artists, the exhibition explores the importance of these women artists who captured the human faces of industrial and domestic labor—and its inherent racial, gendered, and class inequities—while they used their art to support important reforms led by the era’s growing communist and socialist movements. It also links the economic, social, and environmental crises of that period to the present day, demonstrating the critical relevance of these artworks to contemporary issues. An adjacent gallery highlights how WPA artists—both women and men—used the printing press to oppose fascism, creating work about the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), even against governmental orders. Art/Work: Women Printmakers of the WPA is on view at the BMA through June 30, 2024.

“For too long, the work of women has been unrecognized and swept under the rug. In this moment when the topic of invisible labor of women and others is receiving critical attention it deserves, I cannot think of a more apt exhibition to engage our audiences on this issue and its histories,” said Asma Naeem, the BMA’s Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director.”

The exhibition opens with a section that explores the economic, social, and environmental events that shaped the Great Depression and that led to the establishment of the WPA and its many projects, which included large-scale construction and public works initiatives across the United States. Among the highlights in the section are works by Blanche M. Grambs, Margaret Lowengrund, and Claire Mahl Moore that offer three different views of the developing transportation system in New York City, as well as prints by Mabel Dwight and Elizabeth Olds that reflect the profound wealth disparities that led to the economic collapse of 1929 and contributed to the subsequent financial and social turmoil.

Art/Work continues with sections exploring labor through a range of lenses. Women artists were essential to revealing the experiences of the often nameless and voiceless workers in coal mines, factories, fields, and garment sweatshops. Their prints, which shone fresh light on abysmal working conditions and rampant exploitation, were critical to driving reform and supporting worker organization efforts. For example, Ida Y. Abelman’s 1937 Child Labor depicts two scenes of child labor, one urban and one rural, highlighting the extreme demands placed on children who had to work to support their families, while Florence Kent’s Design for Living (1939) contrasts the utopian conceptions of 1930s design with the grim realities of a family eating, sleeping, and raising children in a single room insulated with newspaper. The exhibition also explores the idea of artists as laborers and organizer, emphasizing the supportive social and creative networks as well as formal unions that artists established at this time. These connections were especially important for women and artists of color, who were often excluded from studios and exhibition spaces and thus lacked the opportunities for patronage offered to white male artists. Imagery in this section presents portraits of individual artists and the comradery that they developed.

The exhibition also captures scenes of joy and the significant role of the arts in providing new avenues for celebration and hope. These prints are filled with exuberant dancers, actors, musicians, as well as the cultural and service workers who made performances and events possible. Mildred Emerson Williams’ work Washington Square (1936) also reveals how leisure activity brought people together in civic spaces. The print depicts people of different classes in the public park, with well-dressed women carrying packages, children skating, men and women conversing, and families using the public water fountain. The works in Art/Work offer an expansive view of an evolving American culture in a period of great change and underscore women’s critical roles in both shaping and documenting these happenings.

Art/Work is curated by Virginia Anderson, BMA Curator of American Art and Department Head of American Painting & Sculpture and Decorative Arts, and Robin Owen Joyce, BMA Getty Paper Project Fellow.

About the Baltimore Museum of Art

Founded in 1914, the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) inspires people of all ages and backgrounds through exhibitions, programs, and collections that tell an expansive story of art—challenging long-held narratives and embracing new voices. Our outstanding collection of more than 97,000 objects spans many eras and cultures and includes the world’s largest public holding of works by Henri Matisse; one of the nation’s finest collections of prints, drawings, and photographs; and a rapidly growing number of works by contemporary artists of diverse backgrounds. The museum is also distinguished by a neoclassical building designed by American architect John Russell Pope and two beautifully landscaped gardens featuring an array of modern and contemporary sculpture. The BMA is located three miles north of the Inner Harbor, adjacent to the main campus of Johns Hopkins University, and has a community branch at Lexington Market. General admission is free so that everyone can enjoy the power of art.