Baltimore’s Role in the American Revolution

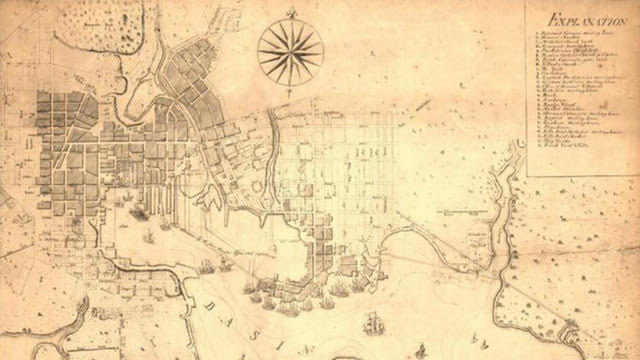

Map of Baltimore, 1792 (Courtesy Library of Congress)

On Sunday afternoon (of course, it was a pre-Super Bowl time), a lecture was held at the fashionable Engineers Club in historic Mt. Vernon Place, near the Washington Monument. Originally, the club was known as the Garrett-Jacobs Mansion. It’s a Baltimore icon and a reminder of its past glory.

Put it on your must-see list. (To learn more, go to. the website.)

The session before a capacity audience was entitled: “From the Stamp Act to Yorktown: A Talk on Baltimore and Its Role in the American Revolution.” Educator and historian Wayne R. Schaumburg gave a very interesting one-hour presentation on the subject. It was sponsored by the “Baltimore Heritage” group. Schaumburg was aided by a slide show. After his talk, he was kind enough to open the program up for a Q&A period.

Schaumburg started by talking about old Baltimore Town. It came into focus, he said, around 1729, “all 60 acres of it.” Next up was Jones Town (think Shot Tower area) around 1732, then Fell’s Point followed, but not until 1773. All three areas became the foundation of what we now know as Baltimore City.

“Baltimore began to take off,” Schaumburg said, when its port started “exporting flour.” Enter the “Stamp Act” in 1765!

When the British government, then-dominated by large greedy landowners who were hell-bent on sucking the life out of colonial America, passed that hated measure, there was wide resistance throughout the country. In Baltimore, the opposition was non-lethal and only in the political theatre. The expression, “No Taxes Without Representation,” was painted all around town, Schaumburg told us. Eventually, the British backed off of the idea and withdrew the oppressive “Stamp Act.”

A British politician named Charles Pratt, (later the Earl of Camden), opposed the “Stamp Act.” He and others, like Counts Barre and Pratt, were rewarded, Schaumburg said, by our local leaders. They had Baltimore streets (and much later, a popular baseball stadium) named after them.

There were four Marylanders, among many, who distinguished themselves in the Revolutionary War (1776-1783), Schaumburg commented. All had strong Baltimore connections. They were: Col. John Eager Howard (lived in Baltimore and Baltimore County); Captain Mordecai Gist (born in Baltimore); Col. James McHenry (born in Ireland, lived and died in Baltimore), and Major Sam Smith. The latter also was in charge of the successful defense of Baltimore during the War of 1812-14, also against the grasping British imperialists.

Fort McHenry, which juts out into Baltimore harbor, was named after Col. James McHenry, who was also a physician. He had served as President George Washington’s first Secretary of War. He is buried in Westminster Burial Grounds (Fayette & Green Streets.)

Note that the popular patriot, John Eager Howard, Schaumburg underscored, had three Baltimore streets named after him, to wit: “John, Eager and Howard Streets.” Howard was also a huge landowner in Baltimore and Baltimore County.

(By the way, Howard also donated the land for the founding of the Lexington Market and the Washington Monument. He contributed, too, the land for the Baltimore Catholic Basilica.

A big question came up at the session: “Did George Washington ever sleep in Baltimore?” The answer Schaumburg said was a resounding “yes.” He stayed at least six times over the years (1775-1789) at the Fountain Inn. It was located at Light and Redwood Streets, on the site that use to house the now-defunct Southern Hotel.

Another key question was answered by Schaumburg. “Was Baltimore ever the capital of our young America?” He answered that in the affirmative, too, by saying that for a three month period, December 20, 1776, to February 27, 1777, the Continental Congress “called Baltimore home.” The British had taken over Philadelphia and forced our patriots out. The Royal Farms Arena now sits on the site of the Continentals’ venue.

Not all the national politicos were happy about residing in Baltimore during that short period of time. One called it, “the dirtiest place I was ever in.” Delegate Ben Rush labeled it: “the damnest hole in the world.” But, good old John Adams came through. He praised the city, “as a pretty town.”

It was during the early days of the war, that Fell’s Point came into its own as a builder of ships. Located across the harbor from Whetstone Point (now Locust Point), it had the deep waters to accommodate such an important maritime effort. Thirteen frigates were built there, some were later used by privateers, like Josuha Barney, who was also an esteemed U.S. Navy veteran. (You’re right if you are wondering if Barney Street, in South Baltimore, was named after him.)

A Baltimore publisher, Mary Katherine Goddard, also a fervent patriot, contributed to the cause of America’s freedom, too. She printed copies of the Declaration of Independence with the signers’ names. Defiantly, at the bottom of the document, she signed her name: “Baltimore, in Maryland: Printed by Mary Katharine Goddard.” (Bless her memory!) The name of her newspaper, Schaumburg stated was, “The Maryland Journal.”

Another of the topics Schaumburg covered was the “Maryland 400.” These were the brave troops, mostly “from Baltimore, Annapolis, and Howard County,” he continued, who fought so heroically in the “Battle of Long Island,” in March of 1776. They held the line against overwhelming British forces allowing Washington’s army to retreat to fight another day. General Washington said of them: “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose.” Maryland’s nickname “The Old Line State” came out of this conflict and their valiant sacrifices, for which they paid a heavy price.

To learn more about these Maryland heroes, check out. There is a monument to them located just across the street from the Modell Performing Arts Center (formerly the Lyric Opera House) on Mount Royal Avenue, near the University of Baltimore.

Schaumburg finished up his compelling talk by commenting on General George Washington. He said that the hero of our Republic wasn’t initially, “the overwhelming choice,” to be the commander in chief of the Continental Army. A percentage of the delegates wanted someone with more experience. At the end of the day, however, Washington got the nod. Mostly, Schaumburg suggested because he was from the influential state of Virginia, and the delegates were cautious about giving, “too much power to the North.”

The rest, as they say, is history!

Bill Hughes is an attorney, author, actor and photographer. His latest book is “Byline Baltimore.” It can be found at: https://www.amazon.com/William-Hughes/e/B00N7MGPXO/ref=dp_byline_cont_book_1