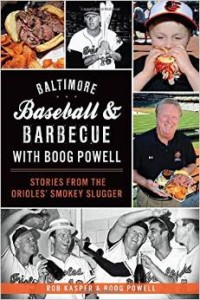

Baltimore Baseball & Barbecue with Boog Powell

Young Luke Schwindt eagerly devours one of Boog’s delicious barbecue sandwiches. (Jim Burger)

The Baltimore Post-Examiner is proud to present two excerpts from chapter five of Baltimore Baseball & Barbecue with Boog Powell. Since he started smacking longballs for the Baltimore Orioles, Boog Powell has enjoyed the gustatory delights of his adopted hometown. A four-time All-Star and a fixture in two World Series, Boog also knows how to make one heck of a pit beef sandwich. With photography by Jim Burger, Baltimore author Rob Kasper takes a heartfelt look at the life of the smokey slugger as told by Boog in his own colorful style. Baltimore Baseball & Barbecue is available locally, as an e-book and online.

Years of Glory and Backyard Barbecues

In the 1960s, Boog Powell came to fruition. Like a ripening heirloom tomato, he started slowly, but when the time was right, he was spectacular.

His slugging, along with that of the Robinsons—Brooks and Frank—led the Orioles to a World Series championship in 1966. It was the city’s first, and the town was in ecstasy. Defensively, he locked down first base, his natural position, and twice finished second in the balloting for the most valuable player in the American League, an honor he would subsequently win.

On the domestic front, his life was expanding as well. He and Jan welcomed their son, John Wesley Jr., or J.W., into the world in 1963. J.W. was joined three years later by his sister, Jennifer.

In Baltimore, the Powell family had taken up residence at 1507 Medford Road, a little less than a mile north and east of Memorial Stadium, just off Loch Raven Boulevard. Several other Orioles (Brooks Robinson, Jackie Brandt, Jerry Adair, Davey Johnson and Dave McNally) also resided in the neighborhood. Often, after a baseball game, they would find themselves in the backyard of the Powells’ row home, feasting on Boog’s cooking.

In Baltimore, the Powell family had taken up residence at 1507 Medford Road, a little less than a mile north and east of Memorial Stadium, just off Loch Raven Boulevard. Several other Orioles (Brooks Robinson, Jackie Brandt, Jerry Adair, Davey Johnson and Dave McNally) also resided in the neighborhood. Often, after a baseball game, they would find themselves in the backyard of the Powells’ row home, feasting on Boog’s cooking.

J.W. remembers as a boy falling asleep in his upstairs bedroom hearing the distant cheers from the ballpark, only to be awakened a few hours later by the laughter coming from his dad’s backyard get-togethers.

“We didn’t make much money, so we all went out together,” Andy Etchebarren, Oriole catcher and Boog’s teammate, recalls. “Boog was a good cook, a big fellow who enjoyed life. He would have parties at his house and barbecue for everybody. He introduced me to Manhattans and to vodka Gibsons with onions in them.”

Boog’s definition of a great night was “playing cards, getting a case or two of National Bohemian and sitting out in the backyard.” (National Bohemian, a wildly popular blue-collar lager made by the National Brewing Company, happened to be owned by the Orioles’ majority owner, Jerry Hoffberger.) “

All those houses were attached,” Brooks Robinson recalls. “I bought my house from the Colts running back L.G. Dupre. They called him ‘Long Gone’ Dupre. Boog bought a house about two houses down from me. Boog partied better than anyone else. He lived large, but he was always ready to play every game.”

Living close to the ballpark and to the families of other ballplayers had several benefits. “Jan and Connie got together,” Brooks Robinson recalled, referring to Boog’s wife and his own. “And kids played together.”

Jennifer, now Jennifer Powell Smith, a senior loan officer living in Longwood, Florida, recalls that when she was a little girl, the Medford Road families would sit together in a section of Memorial Stadium reserved for relatives of Oriole players. “It was fun for us because we got to see all of the families of the other players,” she recalled. “And we had the same ushers, and they would bring Cokes and hot dogs. We loved Family Day, when they brought us sodas.”

Initially, she was upset when her dad came to bat and the crowd hollered, “Booooog!” “I thought they were booing my dad, and I said, ‘Mommy, why are they booing him?’” Her mother assured her that the calls were signs of affection, not derision.

********************************

Once springtime arrived in 1964, Boog was leading the Orioles’ attack. Skipper Hank Bauer put Boog in the third batting slot, reasoning in part that in addition to his power, Boog’s big body would block the view of opposing catchers and give Orioles lead-off hitter Jackie Brandt and number-two batter Louie Aparicio better chances to steal bases. It seemed to help Aparicio, who swiped fifty-seven bases that year, but not Brandt, who stole only one.

Memorial Stadium was not an easy place to hit home runs. The deep power alleys, originally 385 feet in right and left center, required quite a poke, and balls tended to die on the warning track. Still, Boog connected for some massive shots. He smacked a ball over the hedge behind the center field wall in 1962, a wallop of some 470 feet, the first Oriole to clear that landmark. For a while, it was the longest home run hit in Memorial Stadium. But in 1964, the Twins’ Harmon Killebrew hit one in the same vicinity, and his home run was declared to have traveled 475 feet. “That pissed me off— they gave Harmon more footage than me,” Boog said. “I said ‘Come on, he’s a visitor. I am here every day.’”

Despite this dispute, Boog and Killebrew became friends. Five years later, when Killebrew was named the American League’s MVP in 1969, he told Boog that he, the Orioles first baseman, should have been given the award. Both men had impressive statistics that year. Boog knocked in 121 runs, hit 37 home runs and batted .304, while Killebrew knocked in 140 runs, socked 49 home runs and batted .276. Killebrew seemed to have the edge in slugging, but he was gracious. “Harmon told me, ‘I got it, but you deserved it,’” Boog recalled.

The Orioles fell short of the Yankees in a run for the pennant in 1964 despite a strong showing down the stretch by Boog. Waylaid by an injured wrist—a malady that would continue to haunt him throughout his career— Boog missed fifteen games in August and early September. Shortly after returning to the lineup, he launched an epic 475-foot home run over the center-field fence in Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium, telling reporters after the game that his wrist still hurt. His wrist did not heal, but he continued to hit, batting .333 for September and winning accolades from manager Bauer. In summing up the ’64 season, Bauer told reporters that the club had fallen out of the pennant race when its bats went quiet. The exceptions to this hitting draught, he said, had been Boog Powell and Brooks Robinson.

The next season, 1965, Boog slumped, and Bauer, in an exchange that Boog found insulting, ordered him to lose weight or pay a fine. From Boog’s perspective, his weight was his business. When he was hitting well, no one questioned it. But when he struggled, his weight was seen as the culprit.

From the Orioles’ point of view, his production had dropped off, and his bulk had slowed down his timing. Boog’s size had long been an issue of contention for Orioles management. Even as a newcomer, then relatively thin, his eating habits had been topics of concern for Orioles brass. While touting the talents of then-rookie Powell, Oriole general manager Lee MacPhail had told reporters his only weakness were “a knife and a fork.”

Perhaps it was an attempt at humor, but Boog did not appreciate it. He believed that Orioles management was fixated on his weight. “

If I was going good, it didn’t matter what you weighed. They would send a trainer in there, and he would say, ‘What do you weigh today?’ I would tell him, and he would put it down. But when things were going bad, I had to get on the scale,” Boog recalled. “And one year, I came up with shin splints, and Hank Bauer got pissed off. He sent Ralph Salvon in to weigh me, and I think I weighed 262. Hank said, ‘You got two weeks to lose twenty pounds or it is going to be ten dollars a pound.’

“So I bust my ass. I am gonna show them. I was so tired by the end that I could hardly walk. I was hurting. I wore a rubber suit. The day of the weigh-in was a Sunday, a day game, and I got to the ballpark at around eight in the morning. I got in the whirlpool, and Jimmy Tyler set the whirlpool at about 105, which is pretty hot. I stayed in the whirlpool for almost an hour. I got out looking like a lobster.

“I went in and got on the table, and Ralph Salvon covered me with a blanket. I lay there and sweated and kinda took a nap. Finally, I said, ‘Ralphie, let’s get it over with.’”

By his recollection, Boog weighed in a mere half pound over the goal. Press reports say he was over by a pound or more.

The untold story, Boog says, was what happened next. When he heard that Orioles executive Harry Dalton was going to charge him for the overage, Boog confronted Dalton. “I was hot. Harry Dalton was there. He told me they were going to take it out of my check. I went in and got a five-dollar bill and threw it at him. He wouldn’t pick it up.”

Boog finished the year with seventeen home runs, 72 RBIs and a .248 batting average.

Years later, recalling the battles over his weight, Boog was both reflective and resentful: “Someone thought my ideal weight was 240. But when I was going good, Ralphie [Salvon] would weigh me at 275, and not a word was said. Most years I was at 270. [Owner] Jerry Hoffberger was worried I weighed too much and sent me and Jan to a session with an endocrinologist and later a psychologist.” During one session, the psychologist presented Boog with a piece of rubber that resembled a sandwich and asked him to reflect on it.

The session with rubber food pretty much ended Boog’s visits. “I tried to go along,” Boog recalls, but the rubber food was too much. Moreover, he was confident of the way he walked through life. “There is a lot to be said about how I live my life. I enjoyed a few beers after the game. It was a way of relaxing. We would talk about the game. We probably had three beers before we had our socks off.”

Drawing up a chart comparing Boog’s weight with his batting average and home run totals seems to prove little. The weight on Opening Day programs is suspect. Baseball Almanac listed Boog at 240 pounds every Opening Day program of his career. Sports Illustrated’s Opening Day lineups list him at 230 throughout his career. Age might be a more likely factor in production, but it is uneven. His best years the plate were 1966, ’69 and ’70, when he was twenty-five, twenty-eight and twenty-nine years old, respectively. However, in 1975, at the age of thirty-four and playing for Cleveland, he had another stellar year, was named Comeback Player of the Year and had better statistics than he did at twenty-six and twenty-seven.

In 1966, Boog’s batting numbers soared largely because 183 pounds were added to the Orioles lineup in the person of Frank Robinson. Robinson came over to the Orioles in a deal with the Cincinnati Reds. That made the Orioles batting lineup much tougher to pitch to.

Truth be told, Boog at first had mixed feelings about the trade. To get the Cincy slugger, the Orioles had traded Milt Pappas to the Reds. “Milty was a friend and a hell of pitcher,” Boog recalled, pointing out that Pappas would go on to win ninety-nine games in the National League.

Nonetheless, Robinson brought a fierce demeanor to the club, an attitude that Boog appreciated. Robinson chastised his new teammates for chatting with opponents during a game. “Frank said, ‘Screw those guys, talk to them after the game.’ It made sense to me,” Boog recalled. “We would be smiling at you one minute and beat your brains out in the next.”

In addition to tough talk, Robinson swung a big stick, an attribute Boog quickly noted. “When Frank came over to the club, we were down in spring training, and Frank hit one over the palm trees,” Boog recalled. “I turned to Etch [Andy Etchebarren] and said, “Etch, I think we just won the f—ing pennant.”

Boog started the 1966 season slowly, but on May 1 in Detroit, he hit a 415-foot line-drive home run off Tiger hurler Joe Sparma that ignited him and the team. “I came back in the dugout and said to Frank, ‘Here we go, I am feeling good.’ And away we went. When Frank didn’t do it, I did it or Brooksie [Robinson] did it. And if Brooksie didn’t do it, [Curt] Blefary did it. And when Blefary didn’t do it, [Paul] Blair did it.”

The Orioles lineup was deep and talented, and Boog knew opposing pitchers did not have the luxury of pitching around a hot hitter: “Paul Blair was hitting second. With Frank and me behind him, nobody was going to walk him. And you don’t walk Frank to get to me.”

Author Rob Kasper and photographer Jim Burger will be signing copies of Baltimore Baseball & Barbecue at Atomic Books in Hampden – August 21 7pm. They will be joined by Boog Powell at Shorebirds Stadium, Salisbury – August 22 7pm; and in downtown Baltimore at the Sports Legends Museum – September 12 5pm.

(Pictured from left) Jim Burger has been a professional photographer in Baltimore since 1982, honing his skills while working for the City Paper and the Baltimore Sun. Burger’s iconic images have also appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, San Francisco Examiner, Los Angeles Times and Baltimore Magazine.

Boog Powell is a former major league baseball player, spending seventeen seasons with the Baltimore Orioles, Cleveland Indians and Los Angeles Dodgers. Powell was also a marina owner, beer pitchman and television celebrity. In 1992 he opened Boog’s Bar-B-Q at Camden Yards – a concept in ballpark concessions which has since been copied around the United States. A previous book Mesquite Cookery was published in 1986.

Rob Kasper spent 33 years as a feature writer for the Baltimore Sun, winning numerous awards while penning a nationally syndicated column. His previous book, Baltimore Beer: A Satisfying History of Charm City Brewing (2011) was also published by History Press.