Analysis: Spring chill hits Democratic leaders over budget

By Len Lazarick

[email protected]

The body language seemed to convey the lingering hostility. Senate President Mike Miller and House Speaker Michael Busch stood stiffly behind their chairs, waiting for Gov. Martin O’Malley to arrive at Tuesday’s bill signing.

The usual celebratory atmosphere after the 90-day session was muted by the failure to enact the tax hikes the night before, forcing the implementation of a budget with another $500 million in budget cuts.

The chill did not diminish when the governor appeared. He cited successes on the environment and health care, but was still in a funk.

“Sadly, the operating budget was pretty much the low point of my experience here,” said O’Malley, who had set an ambitious agenda for the session. “We cannot change the past, but we can change the future.”

The future is likely to hold an O’Malley order for the lawmakers to return to Annapolis for a special session, as Miller and Busch would like to see. As Busch made clear in a MarylandReporter podcast, he actually preferred that the House and Senate extend the session on their own, but Miller refused after Busch paid a personal and highly visible visit to Miller on the Senate rostrum Monday night.

O’Malley would not discuss calling a special session either Monday night or Tuesday morning, shoving aside the microphone when a reporter asked him about it again.

“He’s not a happy camper right now,” Miller told reporters afterward, referring to O’Malley. “He’ll get over it.”

Miller upbeat, but target of wrath

Miller was the most upbeat of the trio, and the man the other two blamed for the chaotic end of session. There is always drama in the final hours of the General Assembly; bills die as time runs out and some miraculously survive. Monday’s drama was abnormal as these things go. Important bills expire at end of session, but typically not the legislation that smoothes the way for the coming budget.

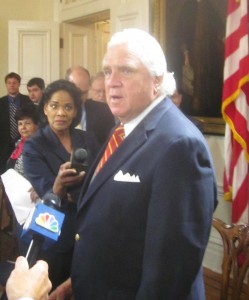

Miller is an ideal target for the wrath of O’Malley, Busch and others. Large and flamboyantly loquacious, he can come off as magnanimous and sensitive leader one moment, and a blustering bully the next, unworried that his 26-year tenure at the Senate’s tiller is in jeopardy. Comptroller Peter Franchot, who made a special trip to the State House press room Monday to complain of Miller’s obsession with spreading gambling, said on the radio Tuesday that Miller should forced out. But having reneged on a pledge to retire four years ago, no one is pushing Miller out the door, as much as they would like to.

“We didn’t fail anybody,” Miller said. “This is a minor bump in the road.” If the legislature comes back for a one or two day session, Miller insisted, “everything will be fine.”

The dysfunction between the House and Senate “happens all the time,” he said. “It’s no big deal.”

Miller praised Busch for his efforts. “The speaker couldn’t have worked harder,” he said. Busch rolled his eyes.

Doomsday was Miller’s brainchild

It was Miller who early in the session came up with the idea of the “doomsday” budget. He wanted unpleasant spending cuts in the governor’s budget that were to happen if legislators did not back tax hikes. The $500 million in cuts – half of them to K-12 and higher education – were designed “to give people the courage to vote” for the tax increases.

No one expected the cuts to be implemented, but budgeters in both houses dug in their heels. “Both sides wouldn’t move,” Miller said. In the podcast, Busch insisted it could have been resolved last week.

Led by Miller, the Senate wanted a larger income tax hike, affecting more taxpayers; the House wanted only people making more than $100,000 and up to pay more, but at a lower rate, raising less money than the Senate. In the final hours of the session, the Senate caved in to almost all the House demands, hardly a model of compromise.

“My conferees are clapping their hands,” Miller told reporters. “They’re pissed off.”

Special session in May likely

Give O’Malley a day or two to cool off and he’ll likely issue the order for a special session to raise taxes, the second of his tenure. Something starting around May 1 is likely for several reasons.

The most compelling reason for lawmakers to come back to finish the job is that they failed to pass not just tax hikes, but the Budget Reconciliation and Financing Act. This omnibus piece of legislation amends more than two dozen state laws, transferring funds and changing funding formulas and spending requirements affecting tens of millions of dollars. Without the BRFA (BUR-fa), the budget is incomplete and can’t be completely implemented. This includes the shift of some teacher pension costs to the counties.

With a week or two, the constituencies most impacted by budget cuts will have had time to get their members riled up: the teachers union facing loss of school funding, college students and administrators facing tuition hikes, state workers no longer getting their first cost of living raise in years.

Other constituencies also have pressing needs. The counties are about to finalize their local budget proposals, most of which must be passed by the end of May. They all depend on state funding. Over the last three years, the counties have lost much of their state aid, but they still need to know the final figure what they’ll get.

More than half of most local budgets go to schools, and the school systems need to know what they’re getting. Will they get what they thought was coming through most of the session, or the doomsday hit? University regents and community college trustees need to know whether they need to raise tuitions to make up for the 10% doomsday cut. State agencies need to know if they must trim operating expenses 8% come July, and whether another 500 state positions must go.

Not to be dismissed is the elimination of the $12 million in scholarships delegates and senators dole out to constituents, often at high school graduation and awards ceremonies in May. Howard County Sen. Allan Kittleman and his father, the late senator and delegate Robert Kittleman, have sought to wipe out this program over the years, but it is popular with legislators.

The GOP in general is happy with this and most other doomsday cuts, which look much like their budget trimming plans with the goal of no new taxes in past years. The Democratic supermajority and its constituencies are not likely to go along.

MarylandReporter.com is a daily news website produced by journalists committed to making state government as open, transparent, accountable and responsive as possible – in deed, not just in promise. We believe the people who pay for this government are entitled to have their money spent in an efficient and effective way, and that they are entitled to keep as much of their hard-earned dollars as they possibly can.