Meet the bikers who try – and fail – each year to erode Maryland’s helmet law

By SAPNA BANSIL

Capital News Service

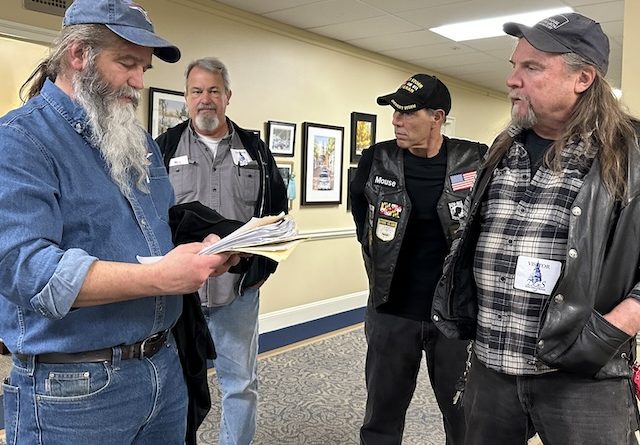

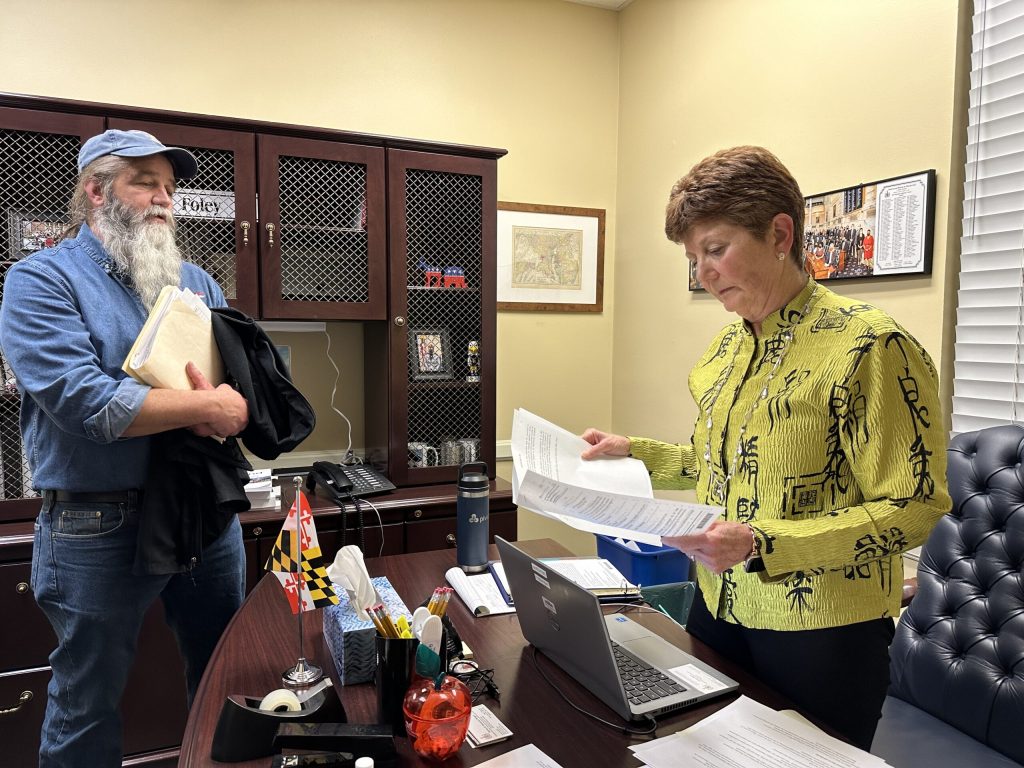

ANNAPOLIS, Md. – A group of bikers in leather vests and wispy beards greets lawmakers here each Monday of the legislative session, hoping this is the year they’ll succeed in their galvanizing cause: gutting a Maryland law that requires them to wear helmets.

The group, which calls itself A Brotherhood Against Totalitarian Enactments, has experienced decades of setbacks on the helmet issue. Its vociferous critics say ABATE’s position is at a minimum, eccentric and at worst, dangerous.

But driven by a burning belief in personal freedom and a joy for riding, ABATE has used persistent, grassroots activism to keep the helmet issue alive in Maryland. It’s why in nearly every legislative session since the state’s mandatory helmet law took effect in 1992, the Maryland General Assembly has at least considered a bill that would make wearing a helmet optional for most riders.

“It’s been 32 years this year to no avail,” said Bob Spanburgh, Maryland ABATE’s board chairman. “But we keep introducing it. We have some pretty ardent supporters. We have a lot of people who think we’re nuts, probably.”

Like many of its previous incarnations over the past three decades, this year’s bill would make wearing a helmet optional if a motorcyclist is at least 21 years old, has been licensed for a minimum of two years and has completed a safety course. It is named in honor of Gary “Pappy” Boward, a former ABATE executive director and motorcycle rights advocate who died in 2020 of health issues.

ABATE and other supporters insist that they aren’t opposed to riders wearing helmets if they so choose. But they feel the current mandate abridges freedom of choice and represents government overreach.

“I firmly believe that we as government do better when we educate people, [rather] than legislating something,” said Sen. Mike McKay, R-Allegany, Garrett and Washington, the bill’s primary Senate sponsor and a friend of Boward’s. “There are people that would like to have the choice [to not wear a helmet.] And I tend to believe that we should give people the choice but 100% support educating them about it.”

Established in 1974, ABATE will mark 50 years of advocacy for motorcyclists’ rights this June. Its animating issue has been eroding Maryland’s helmet law, different iterations of which have been in place since 1968. Today, Maryland joins 16 other states and the District of Columbia in requiring all riders to wear protective headgear.

Spanburgh, a 66-year-old retired carpenter, only casually followed politics when he joined ABATE in the mid-1980s. Initially, he saw the group as a community of like-minded individuals, who shared his enthusiasm for bikes, firearms, the outdoors, and rock and roll. But right away, ABATE turned Spanburgh into an unlikely activist.

“At the first meeting I went to, the thing they told me [was,] ‘You got to register to vote. It’s very important in this organization,’” Spanburgh recalled. “That was actually the first time I ever registered to vote in my life. I was 27 at the time.”

Each legislative session, the helmet bill faces cockeyed glances and prodigious odds. Contending with a wealth of scientific evidence, which shows crashes involving non-helmeted motorcyclists are much more likely to result in severe head trauma and death, the measure almost always dies in committee.

But ABATE ensures the issue is revived and relitigated, year after year, by finding ways to get in front of elected officials, despite limited financial resources and dwindling numbers. In the past, the group used a tactic it called “piss house politics,” which involved following lawmakers into the bathroom to gain an audience and get its message heard.

“They’re diehards for what they believe in,” said Del. Jay Jacobs, R-Caroline, Cecil, Kent and Queen Anne’s. “Thank God they do. They don’t let go of this stuff. It’s a tough fight over here to get that kind of legislation passed.”

While Republicans are the most likely to sympathize with ABATE’s cause, the group engages lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. This year’s bill, cross-filed as HB639 and SB503, has bipartisan sponsors in both chambers.

“I don’t agree with them that they shouldn’t wear a helmet, but I do agree about the civil liberty issue,” said Sen. Jill Carter, D-Baltimore City, one of the bill’s Senate co-sponsors.

“They are adamant as dedicated motorcyclists that this is not something they want mandated to them,” she added.

In a recent hearing of the House Environment and Transportation Committee, opponents included highway safety groups, medical associations and public health officials. They argued that a weaker helmet law would increase motorcyclists’ risk of injury and death, impose an avoidable burden on taxpayers and encumber the healthcare system.

“A lot of people might say, ‘Well, it’s my free will to do whatever I want to do, no matter how stupid it is,’” Gene Ransom, CEO of MedChi, the Maryland State Medical Society, said in an interview. “The problem is, when it comes to healthcare … your decision then ends up costing the entire system a whole lot of money.

“Not only is it the right thing to do and the smart thing to do – logical people wear helmets when they ride a motorcycle or a bike or other things – it also is appropriate from a common good and cost point of view,” Ransom added.

The bill is scheduled for a hearing before the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee later this week. Spanburgh hopes to see the measure make it out of committee and get a vote on the House or Senate floor. If unsuccessful, proponents vow they won’t stop trying.

“If I don’t do it, who else is going to do it?” said Ken Eaton, Maryland ABATE’s executive director. “We try to get other people to help us as much as possible. But if I don’t do it, how can I convince other people to do it?”

Capital News Service is a student-powered news organization run by the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism. With bureaus in Annapolis and Washington run by professional journalists with decades of experience, they deliver news in multiple formats via partner news organizations and a destination Website.