Baltimore Orioles’ Kyle Gibson deserves the Roberto Clemente Award

Major League Baseball sports have innumerable awards and recognitions, but perhaps none more noteworthy than The Roberto Clemente Award.

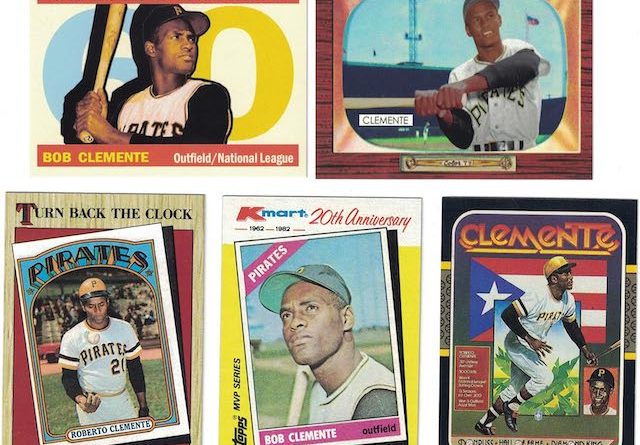

This award, established in 2002, honors the player each year who exemplifies “The Great Roberto,” as he was warmly nicknamed by Bob Prince, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ most charismatic announcer perhaps ever, surpassing even the great Rosey Rosewell of Pittsburgh lore.

The award pays tribute to the players who best personify Clemente’s humanitarianism, decency, and sportsmanship. The coveted citation goes to the player who personifies the national pastime – yes, it still is the national pastime –through, MLB.com states, “extraordinary character, community involvement, philanthropy and positive contributions, both on and off the field.”

Clemente personified all of those qualities and put the ultimate exclamation mark on them when he selflessly perished delivering aid to Nicaraguan earthquake victims in 1972

For the Orioles this year, the nominee is Kyle Gibson, who joined the Birds last December. He is a 3-time Clemente nominee.

Gibson has been immersed in innumerable charities country-wide and is the vice president of Big League Impact; he has hosted fundraisers throughout major league cities and through his philanthropy has raised nearly half a million dollars. Personally, he has donated his own time and money, including $100 for each of his strikeouts this year – ever heard of such a great conflict of interest?

Let me in full disclosure account my personal interest in The Roberto Clemente Award

I wrote an article in USA Today Magazine on Clemente 15 years ago with my closest friend, Lee S. Weinberg. He and I were both co-editors. There had been a renewal of attention in one whom some believe to be the best all-around player ever to have played the game of baseball: Clemente, the right fielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1955-72. We were born and raised Pittsburghers, so, we admittedly are partial to the growing recognition of this remarkable man and player. In fact, one of us at the time occupied an office overlooking a preserved piece of the Pirates’ Forbes Field — the outfield wall at the 436-foot mark–reminding him every day of Clemente’s many heroics.

There was considerable empirical evidence to support our point of view. Clemente was the classic five-tool player, one who could “hit, hit for power, run, throw, and field.” The only dimension for which there is any question at all was his ability to hit for power. His 240 career round-trippers (certainly a more-than-respectable total) still is nowhere near the power numbers put up by some of the game’s all-time great slugging outfielders — Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, and Mickey Mantle were Clemente contemporaries who immediately come to mind.

Roberto reached the 20-homer plateau four times, topping out at 29 in his MVP season of 1966, and he did reach the double-digit mark in home runs in the past 13 years of his career. However, all Pirates players in the “Forbes Field” era should earn a pass in the power department because the erstwhile home ballpark of the Bucs had dimensions of 462 feet to center and 360 and 376 down the lines in left and right, respectively. (Yes, the old Yankee Stadium had its renowned Death Valley, but it was a mere 301 feet down the line in the left and 296 to the foul pole in the right. Moreover, the outfield wall at those junctures was less than four feet high.) Forbes’ dimensions militated against a Pirate’s being a home run hitter, Ralph Kiner and Willie Stargell notwithstanding. Stargell, incidentally, had his home run numbers catapult upon moving to the Pirates’ more reasonably proportioned Three Rivers Stadium (since replaced by PNC Park).

Clemente’s statistics, the home run numbers aside, may not have earned him the title of “best player ever,” but Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post writer David Maraniss (one should say here, parenthetically, that you may infer the greatness of an athlete roughly by who is his main biographer) in his extraordinary Clemente, the Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero made the point that all Clementephiles know, but may not have articulated: Understanding the magnitude of Clemente requires an appreciation of the gestalt of his presence, which was greater than the sum of his statistics: “There was something about Clemente that surpassed statistics, then and always. Some baseball mavens love the sport precisely because of its numbers. They can take the mathematics of the box score and of a year’s worth of statistics and calculate the case for players they consider underrated or overrated and declare who has the most real value to a team. To some skilled practitioners of this science, Clemente comes out very good but not the greatest; he walks too seldom, has too few home runs, and steals too few bases…but to people who appreciate Clemente, this is like chemists trying to explain Van Gogh by analyzing the ingredients of his paint. Clemente was art, not science.”

This book by Maraniss is as comprehensive and accurate a work on a major sports icon as we have read. If there is a weakness (and there is not much of one), it is that no one–even after reading this moving, informative work–will know the truth concerning the much rumored (and possibly – possibly — apocryphal) knife fight that was said to have occurred between Clemente and teammate Elroy Face, a player whose ugly racial prejudices never received the publicity they – and he – deserved.

This is not to say that The Great Roberto lacked impressive statistics. Beginning in 1960, he hit over .300 for 12 out of the next 13 seasons (slipping to .291 in 1968, a season hailed as “The Year of the Pitcher;” in fact, the major league mounds were lowered following that campaign), winning the National League batting title four times.

He made 14 All-Star appearances, and he won 12 consecutive Gold Glove awards. His arm was without equal. To watch him throw his invariably accurate missile to get a man at home or pick off a runner at first who took too wide a turn after a single will never be forgotten. His throws to home were invariably precisely accurate, unlike most of the wide throws one witnesses today. To this day (literally days ago, in mid-to-late September) Mike Wilbon on the excellent Pardon the Interruption, referenced Clemente when an impossible fielding play was made.

Clemente was a product of his time, of course, and his time in baseball from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s was a period of de jure racial discrimination–especially through the mid-1960s–and de facto discrimination for much of the rest of his career. He had to endure racial slights, including the inability to participate in many public events when the Pirates were in Florida for spring training, as well as a multitude of slights when he played in Pittsburgh. Highly relevant to him were the obvious racial differences in earning a place on the roster for blacks and Puerto Ricans, as well as the racial indignities evidenced by baseball writers who quoted his dialect disparagingly, as in “Let Me Peetch,” a Pittsburgh paper’s headline concerning Clemente’s complaints about pitchers who too often tried to back him off the plate with hard inside offerings. More serious, there were individuals such as Les Biederman, a Pittsburgh sportswriter, who lobbied against Clemente’s winning the National League Most Valuable Player Award due to, Clemente felt, his being a dark-skinned Puerto Rican.

The late Pittsburgh sportscaster Sam Nover’s interview show, “Nover One-on-One,” provided one of the best sports interviews we ever have seen or heard. It was aired on Oct. 8, 1972, and rebroadcast on Jan. 1, 1973, immediately following the hero’s death in an airplane crash after his brave effort to bring relief to the people of Nicaragua who had endured a devastating earthquake. One of the authors was involved in the genesis of that interview. He contacted Nover, a WIIC sports reporter, and suggested that he interview Clemente not primarily as a baseball star, but as an interesting person. Although Nover did not know the caller, he was receptive. “That’s a great idea,” he replied, and months later moderated the affecting talk.

The conversation between Nover and Clemente was information-filled from beginning to end. What a pleasure it is to watch an interview that seeks to know a star. The reporter and Clemente discussed the latter’s philosophies of life, his commitment to everyday people, and his difficulties dealing with prejudicial individuals in the space of his 18-year career. He talked of discrimination when simply shopping for furniture, arguing plaintively that he just wanted to “be treated equally.”

He spoke of his closeness to the good American worker, and even though he was considered one of the best baseball players of all time, he particularly revered “honest work,” saying that no one, including himself, ever should be ashamed to do “any job.” He said he wanted his children to be good and decent people and did not think it would benefit them to be rich. He also spoke of the lack of exposure he received being a Pittsburgh Pirate, in contrast to those who played in New York or Los Angeles.

The major memories of Clemente are baseball images that those who watch sports with any regularity have seen repeatedly: his great speed in the outfield and on the bases; his idiosyncrasies like the neck-twitching for a time before he walked up to the plate; his clutch bat that, in addition to the above-cited statistics, showed his hitting in every World Series game in which he ever played; and, above all, his singularly great arm that had to be seen to be believed and which cannot be adequately summarized by statistics–that, by necessity, leave out all of the runners who did not take an extra base or score out of fear of being thrown out.

Clemente’s death clearly was outlined in a New York Times story on Jan. 2, 1973, which stated the following after his plane crash: “Days of national mourning for Mr. Clemente were proclaimed in his native Puerto Rico, where he was the most popular sports figure in the island’s history…he led the Pittsburgh Pirates to two world championships, in 1960 and 1971, the latter time being named the Most Valuable Player in the World Series. Mr. Clemente was the leader of Puerto Rican efforts to aid the Nicaraguan victims and was aboard the plane because he suspected that relief supplies were falling into the hands of profiteers.”

However, similar to the disjuncture between his statistics and his impact on the game, the story missed the totality of the ramifications to baseball, Pittsburgh, Puerto Rico, and baseball fans and humanity everywhere who lost the man after whom The Roberto Clemente Award — given yearly since his death to the player who best exemplifies “character and charitable contributions to his community”– was named. With perhaps one exception (Pete Rose), the recipients have been the best all-round players-as-people the sport has to offer.

Originally named the Commissioner’s Award, it is a poignant reminder that an Oriole who could have qualified for The Roberto Clemente Award, Brooks Robinson, had it existed when he played, passed away Wednesday. He did win the Commissioner’s Award 2 years before it became the Clemente Award. He had the very qualities of playing and personal excellence that Roberto Clemente had, and he, too, will provide cherished memories forever.

Other Orioles have populated the winners’ circle well beyond their expected numbers of the award before and after it became the Roberto Clemente Award: Cal Ripken, Eric Davis, and Ken Singleton

Kyle Gibson’s dedication to the values and accomplishments of The Great Roberto eminently quality him for the Roberto Clemente Award; consider issuing your vote for him.

This year’s nominees:

- Arizona Diamondbacks – Nick Ahmed

- Atlanta Braves – Matt Olson

- Baltimore Orioles – Kyle Gibson

- Boston Red Sox – Tanner Houck

- Chicago Cubs – Marcus Stroman

- Chicago White Sox – Liam Hendriks

- Cincinnati Reds – Hunter Greene

- Cleveland Guardians – José Ramirez

- Colorado Rockies – Kyle Freeland

- Detroit Tigers – Miguel Cabrera

- Houston Astros – Jeremy Peña

- Kansas City Royals – Salvador Perez

- Los Angeles Angels – Mike Trout

- Los Angeles Dodgers – Chris Taylor

- Miami Marlins – Jorge Soler

- Milwaukee Brewers – Christian Yelich

- Minnesota Twins – Carlos Correa

- New York Mets – Francisco Lindor

- New York Yankees – Aaron Judge

- Oakland Athletics – Tony Kemp

- Philadelphia Phillies – Kyle Schwarber

- Pittsburgh Pirates – David Bednar

- San Diego Padres – Tim Hill*

- San Francisco Giants – Brandon Crawford

- Seattle Mariners – Marco Gonzales

- St. Louis Cardinals – Paul Goldschmidt

- Tampa Bay Rays – Shane McClanahan

- Texas Rangers – Jon Gray*

- Toronto Blue Jays – Vladimir Guerrero Jr.

- Washington Nationals – Josiah Gray

Richard E. Vatz https://wp.towson.edu/vatz/ is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of political rhetoric at Towson University and author of The Only Authentic of Persuasion: the Agenda-Spin Model (Bookwrights House, 2024) and over 200 other works, essays, lectures, and op-eds. He is the benefactor of the Richard E. Vatz Best Debater Award at Towson. The Van Bokkelen Auditorium at Towson University has been named after him.