Photographer Sean Scheidt captures Baltimore Uprising

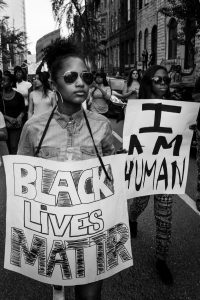

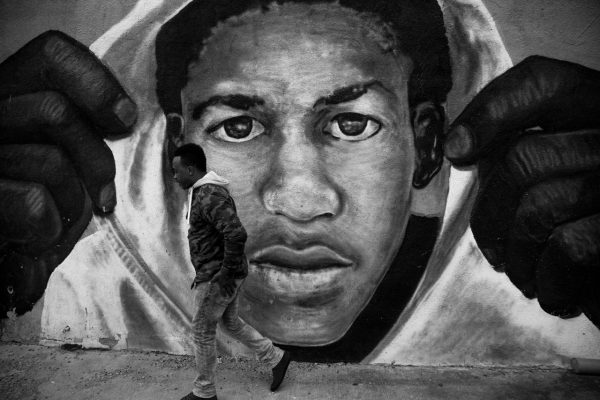

In early May, 2015, The Maryland Historical Society issued a call for images documenting the Baltimore uprising. More than 12,000 images were submitted by photographers from all walks of life, including photographs taken from cell phones and cameras, audio segments, oral histories, and more than 2,000 intergovernmental emails surrounding the unrest that were released by Baltimore City. The images – which depict activists, demonstrations, the presence of the National Guard, police officers, military hardware, and more – are part of the society’s newest exhibit: What & Why: Collecting at the Maryland Historical Society. What & Why opens today, June 29, 2016 and runs through June 30, 2017.

The Baltimore Post-Examiner recently spoke with one of What & Why’s contributing photographers – fashion photographer Sean Scheidt – about his experience documenting the final days of the uprising, and about his new book where he endeavors to tell exactly what he saw “as honestly as possible”.

BPE: It’s great to speak with you again. The last time we talked, you were working on your burlesque transformation series. Given your background as a fashion photographer, we were surprised to learn that you have just released a book about last April’s Baltimore uprising. Please tell us about it.

Scheidt: The book “Uprising” has about 60 images. I culled them from several hundred I had put up on my website shortly after the uprising. Rather than break it down day-by-day, I just let the images tell the story. In some cases, I went with black and white, because I found the color to be too distracting.

BPE: The book is self published?

Scheidt: Yes, I tried to make it as cheap as possible to make it available to a wide audience. I also tried to step back from my own viewpoint and tell the story as honestly as possible. That’s not always easy. In the end, people should know this is just one of many viewpoints seeking to document what happened.

BPE: At what point during the unrest did you decide to start taking pictures?

Scheidt: I hit the streets that Tuesday after fulfilling some morning commitments. At the moment the unrest started on Monday afternoon, I was on my way to a meeting in the city. The situation was chaotic, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to get close to it with my camera. I just decided I’d go out the next day to see what I could capture. In the meantime, I opened my house up for friends from the city who didn’t want to be close to the violence.

Over the next three days, I went to every protest which was being held, including the big one which brought three different groups of protesters together. It was incredible. I’ve never seen anything like it. I was born in 1983 – long past the 1968 riots.

The news kept showing images of angry black people. My images told a story of a fairly diverse crowd allied with them. One 67-year old woman in Sandtown with her hands outstretched was crying. I approached and introduced myself, then asked why she was crying. She replied, “I’ve never seen such a crowd here for us. There are White, there are Black, there are Asians. There are young and old.” I thought that said something incredibly powerful. There was a hope which carried on beyond the protests for some actual change. When I shared the images with my predominantly white family, that was the first thing they noticed, too. I believe that changed their view of what was going on in the city.

BPE: Leafing through the book, I recognized the image of Anderson Cooper at City Hall. Where were the others pictures taken?

Scheidt: Most of them were taken in Sandtown, though a number are along routes from City Hall to Penn North or to Station North.

BPE: So what you saw as a photographer covering the protests was markedly different from the news on the cable outlets?

Scheidt: Absolutely. I sat there the first night with my friends watching every screen we could get a look at. We got most of our news from Twitter and Periscope, while CNN kept playing the same few clips. There was even some controversy that CNN was playing footage of rioting in some South American country. That’s why I thought it was important to include that picture of Anderson Cooper in the series. It was at that point outside media had come in to tell our story.

I’m not a photo journalist. I make my own worlds as a portrait and fashion photographer. But it’s our city. It’s our story. I never felt that draw before. It was just a weird feeling, to step out the door and see smoke on the horizon. You say, ‘What can I do?’ and I had just one tool at my disposal – my camera.

The closest I’d ever come to documentary was the burlesque series and that was a very constructed exploration. But with my camera, I could document what was happening, certainly for posterity. And the hope is there that the images will also help to effect a change.

BPE: Some of your images certainly run counter to what the mainstream media were presenting. Did you get any blowback?

Scheidt: Of course. I could only see what I could see and go where I could go. I had one very vocal opponent, and that was a friend’s wife. She’s in the army, and as I was tweeting photos, she was dogging on me for not showing the police and national guard in a more positive light. I said, ‘If I see it, I’ll take it. I will take that photo. But right now, that is not what I am seeing.’ It turned out in the end that I did get a photo of a little Black baby giving a high-five to a national guardsman. It was clear the guard did not want to be there. The situation on the ground was tense.

BPE: Some photographers had trouble while covering the protests. I know both Kaitlin Nëwman, who worked for the Sun, and J.M. Giordano from City Paper were knocked to the ground by the police. Did you encounter anything like that?

Scheidt: I did not have problems with the police, per se. But I also did not place myself after hours at Penn and North. For one, I did not have a press pass because I’m not a press photographer. Two, it was mostly photographers after the first night. You had 1-2 protesters making a scene and 20-30 photographers causing trouble and getting into direct conflict with the police. I just didn’t think that was very helpful. I was constantly in touch with Kaitlin to see what was going on and she said it was pointless to come down. So some of the problems with the police were created by the media.

BPE: That’s an interesting take.

Scheidt: Does it make good images? Sure. Does it tell the story accurately? That, I don’t know. But again, I’m not a photo journalist, so I’ll leave it to them to deal with the ethics. From my perspective, what some of them were doing was not helpful.

As photographers, we do have a responsibility for the images we share. I certainly wasn’t going to ignore a sight of people having a good interaction with the police. I think it’s important to spread that message.

BPE: You said you had no problem with the police “per se”. Would you elaborate?

Scheidt: Most law enforcement I encountered were fine. They were so tired and bedraggled looking. The National Guardsmen were very hostile during the biggest protest. There was no real plan of where to go, and for a while they were struggling to keep order. I’m not sure why they had to, because the city was basically shut down at that point. They were actively pointing guns at people. I don’t know how they were armed; if they had rubber bullets. They were trying to keep people off of the Jones Falls Expressway and divert them onto the Fallsway. It was pretty hairy, but that was the closest I came to any sort of altercation.

BPE: You came away unscathed?

Scheidt: I did fall off a wall while trying to jump around. Other than that, I could hardly walk for three days because I was so sore at the end of it all. I think I logged somewhere around forty-one miles of walking in the four days I was out. One man had a heatstroke seizure during one of the marches and my friend Kristen, who was accompanying me, pretty much saved his life. She’s a registered nurse. He collapsed and she just took control until they could get him to a hospital.

BPE: Do you have a favorite image?

Scheidt: The one of the woman I mentioned before is the one I always talk about. There is also one of the guardsmen at the protest march along the Fallsway. They were not happy. What I particularly like are the more hopeful ones. A jazz player; children making art in front of the burned out CVS. They show a side the media certainly didn’t show. I also like the image of the woman who was diving in her car, but could not get by because of the protests. She just got out and put her fist in the air in a sign of solidarity with the protesters. The look on her face is resolute, as if she is saying, ‘I’m with you.’

The other image which comes to mind is the one I used for the cover. The police helicopter. No matter where we went it seemed like there were police helicopters overhead and snipers on the roofs. It was a bizarre feeling. I wondered to myself, ‘Isn’t this the land where we’re allowed to assemble and peacefully protest without the threat of being under arms?’ When do we get to the point where we have a protest zone and if you step outside of the zone, your life is at risk? It was really surreal. What did they expect at that point? There was no more rioting happening.

BPE: Do you think that police presence had anything to do with the absence of rioting during those later protests?

Scheidt: Yes and no. I think the protests would have fizzled out on their own. Baltimore has this strange dichotomy. There were people in Federal Hill who were upset that there were no guardsmen there to protect them. Protect them from what? There was nothing going on there. But then you had entire communities where you had to wake up every day and explain to your kids why there were armored vehicles in the alleyways and soldiers standing in front of the house. In some areas that came off as being occupied, and I think that’s problematic. I get that you need safety and order, but what I saw was their presence was more exacerbating than calming. And the curfew? It’s silly how long it lasted. People were trying to clean up and return to normalcy. So much for the hyperbole about the Battle of Baltimore.

* * * * *

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”