What Democrats don’t get about 2014

The DSCC’s shameful and dismissive treatment of a promising Senate candidate may hobble the party in the entire state for years to come. It’s a familiar story… but that only makes it worse.

Last week’s reports that the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee will take out a $10 million loan to fuel a major closing push for the midterms indicate a smart move. It’s much better to finish the campaign in debt, knowing you gave your team’s players all the assistance they could use, than it is to finish with zero debt but look at a narrow playing field on Election Day, and wonder what might have been.

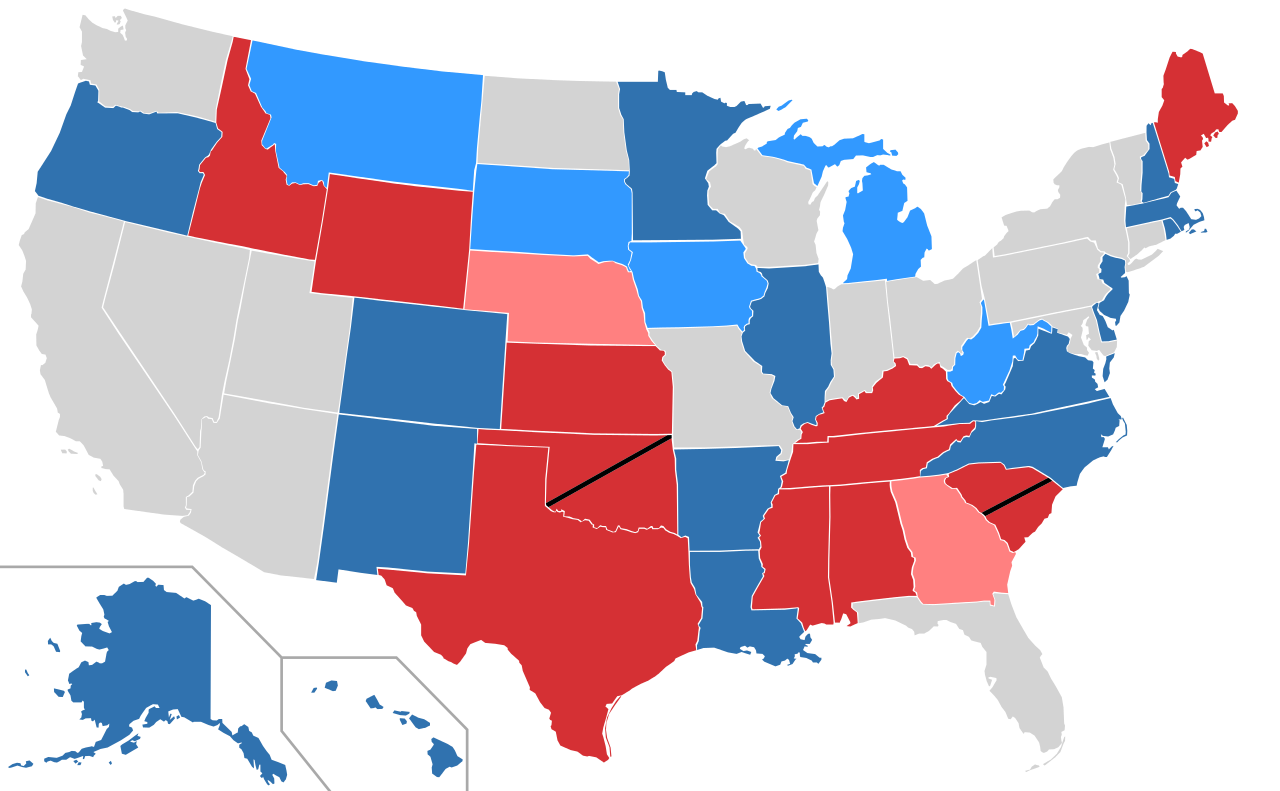

But on Wednesday morning, November 5, Democrats might still be treated to a time of excruciating second-guessing. If they hold the Upper Chamber, the dominating emotion will be relief. A loss of five seats will be something to crow about, and Team Blue will celebrate. But this outcome will only be perceived as a victory thanks to the low expectations Democrats have going forward. With only two or three chances to play offense on the map, Democrats are playing not to lose. But did it have to be this way?

What if national Democrats treated every Senate race, even those that are seen as being safely in the GOP column, as a race they had a duty to make a play for and compete seriously in? It might sound naïve at first blush – we can’t go spending precious money in Idaho, insiders would say, when there are tossup races on the map. That’s logical and valid.

But there’s a difference between pouring money into a lost cause and going through the basic motions of propping up every 2014 Democratic candidate. It’s clear that, with finite resources and several races that are obviously at a tipping point, the DSCC can’t throw away money at hopeless candidates. But why can’t it, at the very least, endorse every scandal-free and competent Democrat on the ballot. Why is it that Joyce Dickerson, the only black woman to be running for Senate this year, has been ignored by national Democrats even as the party’s strategists acknowledge that Democratic hopes this year hinge on heavy black turnout?

It costs the DSCC nothing to endorse their own candidates, and it sends a powerful fundraising signal to Democratic donors. So why doesn’t DSCC head Michael Bennet, who knows better than anyone the importance of minority turnout in surviving close races, have the organization issue a statement of support? Why is the National Organization for Women (NOW) dragging its feet with their endorsement of her, muddling through stalled communications with her campaign as the midterm battle enters its late phases?

Last March, it was considered big news that the DSCC was endorsing Democrat Shenna Bellows in her struggle to unseat longtime Senator Susan Collins. The endorsement reflected some unexpected momentum in the challenger’s campaign; she had actually managed to outraise the incumbent in the last quarter.

It makes sense, until you think about it for a second. Why is it news at all that the organization charged with electing more Democrats in 2014 is endorsing its party’s nominee for Senate? It costs absolutely nothing for the DSCC to say some kind words about even the most long-shot challengers representing the party this cycle. If Bennett can’t direct money towards every last candidate, can he at least be on the record as supporting them all?

It might seem like a ceremonial distinction, the difference between a candidate going down to a 30-point defeat and a similar rout after being given some face-saving attention. But the DSCC’s cold shoulder is not only unnecessary and inexplicable; it sometimes carries with it some very harmful consequences.

In the spring of 2010 Elaine Marshall was a candidate for Senate in North Carolina that either party would have been lucky to recruit. She was popular and electorally experienced, having won her campaign to be Secretary of State in North Carolina by double digits, a margin that exceeded both Kay Hagan’s numbers and President Obama’s. Yet the DSCC made it immediately clear they preferred another, state senator Cal Cunningham, to challenge Republican Richard Burr that fall.

What ensued was a nasty primary made even more harmful by the DSCC’s treatment of Marshall. Her campaign was cash-starved and ignored, and when she prevailed in the primary, the DSCC didn’t welcome her to the general election in any spirit of reconciliation. It ignored her completely to focus on other challengers nationwide. By November, Marshall’s campaign was not on speaking terms with the national party; the icy relations made it impossible to coordinate messaging and ground game efforts together, even if either side had wanted to.

What’s interesting is that despite the DSCC’s open disdain for Marshall, she ended up doing better on election night than a handful of Democrats the DSCC had enthusiastically backed. After the insults she’d endured, Marshall still placed better than Democrats Paul Hodes of New Hampshire, Lee Fisher of Ohio, and Robin Carnahan of Missouri. She wasn’t just a strong candidate on paper; despite what the DSCC had donors believe, she was strong on the trail as well.

The tragedy is that, while Marshall still wouldn’t have won with DSCC help (probably), a slightly stronger performance fueled with money from the national party could have had reverberating consequences. North Carolina was a disaster for Democrats in 2010; the party not only lost five congressional seats, it also lost both chambers of state government for the first time since Reconstruction.

What would have happened if Marshall had run just a point or two better statewide? Lower-level Democrats might have been saved by her coattails; Congressman Bob Etheridge might well have mustered the 1,483 extra votes necessary to save his career. Democrats might have held on to one or both chambers in Raleigh, staving off a far-right state government that would make national news with its exploits, and even more crucially, gerrymander North Carolina to within an inch of her life while sending electorally-incubated ideologues to Washington.

But it wasn’t to be, and Democrats should ponder why the national party turned away in North Carolina’s hour of need, only to see an epic electoral meltdown. It’s a story that’s reminiscent of the old fable. “For want of a horseshoe, a horse was lost. For want of a horse, a soldier was lost. For want of a soldier, a battle was lost. For want of a battle, a war was lost. For want of a war a kingdom was lost, and all for the want of a horseshoe.”

There are some worrisome parallels between North Carolina in 2010 and South Carolina in 2014. Both states presented or present Democrats with huge potential electoral rewards; South Carolina this year is home to a competitive gubernatorial race in addition to not one but two Senate races. The Democratic Governors Association, to its credit, has learned from 2010. After their 2010 nominee Vince Sheheen came within four points of an unassisted upset in 2010, they’re providing him with what he needs this cycle.

But what of the other candidates? With the entire state serving as a prime pickup opportunity for Democrats, there’s no excuse to leave other candidates out to dry, and in a race where every last vote matters, it’s actually counterproductive to do so. Joyce Dickerson may not win. But until she’s given the resources other Democrats take for granted and is left to sink or swim on her own, who is to say she can’t?

South Carolina is in almost the same trajectory its northern neighbor found itself in during the last two months of 2010. Strategically vital, obviously promising, and inexplicably ignored, it could, even now, become the surprise success story of 2014 – if national Democrats wake up. There’s simply no downside to competing there.

Or it could meet the same fate as North Carolina, consigned to GOP rule as a promising Democratic candidacy is snuffed out by clueless and indifferent party operatives. As the people of its northern neighbor can already tell them, it’s not a very pretty picture. But it’s going to become an increasingly familiar and sad midterm story, unless and until the DSCC wakes up.

William Dahl is a recent graduate of The College of William and Mary, where he majored in Government and studied abroad in La Plata, Argentina. He has worked for community foundations in Argentina and Miami dedicated to community engagement and prosecution for human rights abuses. A native Virginian, he moved to Baltimore in 2013 to join a financial research firm, where he enjoys being able to write on the side.