Nations Jobs Report: ‘Good News America. Not so good, Baltimore.’

BALTIMORE – The deep thinkers in Washington are applauding the latest U.S. jobs numbers, but what should we say to the thousands around here who work for giant Amazon, at low wages, in the precise locations where thousands from earlier generations made a pretty good living at factory work.

By coincidence, the government last week released national job figures at the same time the New York Times ran a front-page story headlined, “Amazon’s Expansive, Creeping Influence in an American City.”

Good news, America. Not so good, Baltimore.

The news about U.S. jobs seems remarkably encouraging on the surface. In its November report, the Labor Department cited 266,000 new jobs and the lowest unemployment rate – 3.5 percent – in 50 years.

That’s the 21st consecutive month of unemployment at 4 percent or lower, and it’s part of 11 years of economic expansion.

Ironically, the big jump in new jobs was helped considerably by the return of tens of thousands of striking General Motors workers. It’s ironic because Baltimore once had generations of people working for GM – and thousands more for Bethlehem Steel – and both of those long-since closed locations here are now home to Amazon warehouses.

But here’s the difference: those old GM and Beth Steel workers made a pretty good living for a long time, and the Amazon employees mostly do not.

As The New York Times reporter Scott Shane (who previously worked for The Sun) wrote last week, of the Amazon operation here:

“Computers monitor workers during grueling 10-hour shifts, identifying slow performers for firing. Those on the floor earn $15.40 to $18 an hour, less than half of what their unionized predecessors made. But in Baltimore’s post-industrial economy, the jobs are in demand.”

Consider that phrase: “less than half of what their unionized predecessors made.”

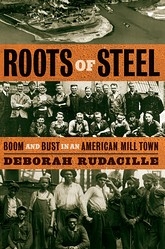

What was it like when places such as Bethlehem Steel employed thousands of factory workers at good wages? In “Roots of Steel: Boom and Bust in an American Mill Town,” her 2010 book on Baltimore, Deborah Rudacille wrote:

“Year after year, the ovens, furnaces and finishing mills of the great works on the Chesapeake belched fire and smoke, crafting the ships and armaments that helped win world wars I and II and churning out the raw steel and finished products that were the backbone of postwar America. In 1959, Sparrows Point claimed the title of the largest steelworks in the world.

“Year after year, the ovens, furnaces and finishing mills of the great works on the Chesapeake belched fire and smoke, crafting the ships and armaments that helped win world wars I and II and churning out the raw steel and finished products that were the backbone of postwar America. In 1959, Sparrows Point claimed the title of the largest steelworks in the world.

“Steelworkers were among the best paid of all Baltimore’s industrial workers in the post-war boom, and their union wages sent many children like me to college. But by 1985 the American steel industry was on the ropes, and on the Point, as elsewhere, jobs were cut, layoffs were made permanent, and mills were closed.”

At its peak, Beth Steel employed 36,000 people here. But, as Rudacille wrote a decade ago, “In little more than a generation, an industrial economy that enabled people without much formal education to create stable families and communities has become a technocratic one in which most of the nation’s wealth in the form of both wages and investment flows inexorably to the best-educated, most affluent Americans.”

And those aren’t the thousands of folks now scrounging for wages at Amazon operations here. The company reportedly accounts for 40 to 50 percent of online retailing in the U.S. Its total value on the stock market is the fourth largest among American companies.

But we’re left with a picture of its workers running around the floor of Amazon warehouses, hoping to hold onto minimum-wage jobs – for the moment. But moments are fleeting. What happens to all those jobs when creeping automation arrives, as it inevitably will?

Where do Baltimore workers go then? Where do America’s?

Michael Olesker, columnist for the News American, Baltimore Sun, and Baltimore Examiner has spent a quarter of a century writing about the city he loves.He is the author of several books, including Michael Olesker’s Baltimore: If You Live Here, You’re Home, Journeys to the Heart of Baltimore, and The Colts’ Baltimore: A City and Its Love Affair in the 1950s, all published by Johns Hopkins Press.