Sand mining coming to a town near you

The state of Wisconsin is no longer a hot bed for metallic sulfide mining, having its Legislature kill a bill in March that would have streamlined mining permit process in favor of mining companies. But it is one of the hotbeds for another type of mining, sand mining, a billion-dollar business.

The process known as “fracking,” for hydraulic fracturing, is used by natural gas and oil drillers to more easily get the fossil fuels out of the ground, requires sand that is nearly perfectly round and has strength to withstand the process. Sand, water and toxic chemicals are blasted into wells, creating fissures in the rock and freeing hard-to-reach pockets of oil and natural gas. Mining firms can get $200 a ton for the sand.

Sand mining was popular in the 19th century, especially on Federal Hill in Baltimore, where workers mined for sand and glass – a booming business for the port city. But in more recent times Maryland has come down hard on companies that pollute the environment. In November 2010, Laurel Sand and Gravel, and 1325 G Street Associates, the limited partnership that is managing the development of the mixed-used Konterra Town Center, in Maryland, paid a $170,000 fine for sediment and water-pollution violations. They were found to have unlawfully “discharged wastewater, failure to follow an approved erosion and sediment control plan, and failure to comply with the mining permit at four current and former surface mining sites.”

Best fracking sand in Wisconsin

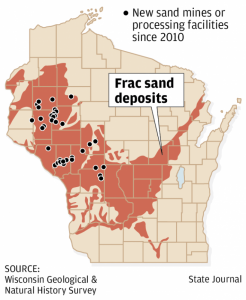

While Texas and Illinois hold the market share in mines, Northwestern Wisconsin boasts some of the best fracking sand in the country and is in the midst of a sand rush of sorts. Companies are eyeing that part of the state with such fervor that regulations and zoning issues can’t seem to keep up.

And fracking has also hit the national dialogue as the federal government has issued standards for air and water pollution by some fracking drillers. The fracking sand rush started about three years ago in Wisconsin. Now, at least 16 frac-sand mines and processing facilities are running, and at least 25 more mines are planned across 15 Wisconsin counties.

Once the open pit mines began moving earth, neighbors got worried about all the dust in the air. The process has raised fears of health problems from land, air, and groundwater pollution which could include cancer and silicosis, a potentially fatal lung disease.

The state Department of Natural Resources issues permits for wastewater and stormwater disposals, but there are no regulations regarding air pollution from the dust drifting off sand trains heading west to the oil and gas fields. And mine neighbors aren’t happy about sand getting into their homes and everything in them.

Industry types say fears are overblown. The DNR hasn’t done anything about air pollution because they say they can’t measure how much sand is blowing around. In 2004 the agency was advised to regulate silica as a hazardous air pollutant. A draft report prepared by the agency notes that the silica can affect people around the mines and sand-hauling trains, but says further study is needed. No matter that they haven’t really required air monitors around sand mines to find out. The only definitive work in the area of lung cancer risk looked at mine workers and found a connection. The latest from the DNR says they are not interested in further regulation.

Mining companies also seem to be targeting townships and unincorporated communities because they lack zoning rules that could contain the mines.

The feds don’t regulate silica and most states don’t either. Texas, California, Massachusetts and Vermont have some state oversight to the process. Vermont recently voted to ban fracking drilling until 2016. Twenty-four states considered fracking bills in some form or another in the past year. Thirty-two states have drilling operations that use fracking.

Fracking has also come to the fore in Ohio, where it was reported this week that the state is at a total loss to find enough drill site inspectors to monitor the pollutants. The feds also face such daunting odds. In New Mexico alone, there are more than 30,000 wells with only 69 inspectors.

The feds are, however, ready to regulate air and water pollution coming from fracking sites in oil and gas exploring, albeit with a limited scope. It recently announced that it would look at methane emission and regulate drilling on federal lands only. Despite vociferous outcry from drilling companies, the rules end up affecting very few operations. The plan would cover about 11 percent of the natural gas drilling and 5 percent of oil drilling in the U.S. About 3,400 wells are being drilled each year on public lands through fracking.

A key factor left out of any proposals is requiring companies to disclose what chemicals they are using in the process. It is a key for regulators to see how the groundwater may be affected by the injection of all those chemicals. The companies are hiding behind “trade secrets” to keep the information private. Drillers would also not have to say what chemicals they use until after the drilling is done. The first draft of the rules required pre-drilling disclosure, but that was removed after a special White House meeting between the Obama administration and mining firms.

The rules stand as proposed right now and there will be a 60-day comment period first.

(Read more mining stories here.)

(Feature photo courtesy of PRWatch.)

Doug Hissom writes a weekly environmental column for Baltimore Post-Examiner. He has covered local and state politics in Wisconsin for more than 20 years. Over the course of that time he was publisher, editor, news editor, managing editor and senior writer at the Shepherd Express weekly paper in Milwaukee. He also covered education and environmental issues extensively. He ran the UWM Post in the mid-1980s, winning a Society of Professional Journalists award as best non-daily college newspaper. An avid outdoors person he regularly takes extended paddling trips in the wilderness, preferring the hinterlands of northern Canada and Alaska. After a bet with a bunch of sailors, he paddled across Lake Michigan in a canoe.