Sherlock Holmes, My Dad and Me

It took me seven years to land my first publishing contract — which is actually not terrible by industry standards. But it meant that I’d had the dedication on my first novel picked out for at least that long: To my dad, who taught me to write.

When I was in my last year of college, required to complete a thesis for honors in English, my dad effectively told me, Write a novel, then drove me to the computer store, bought me a laptop, and walked me through the writing process from the outlining stage on.

But actually, my dad’s lessons in writing — and in life — started much earlier. While I was growing up, we had two unspoken requirements for membership in our family: a love of the written word, and a love of a good mystery. Both were easy as far as I was concerned; I’d had my nose in a book practically from the moment I could recognize words on the page, and graduated from the mystery aisle in the library children’s section to reading Agatha Christie and other classic British mystery greats before I was out of elementary school.

I almost never read Sherlock Holmes stories — arguably the greatest British mysteries of them all — by myself, though. Those stories were special; they were for my dad and me.

When I was very young, my dad supported our family as a full-time novelist. He was — in my obviously unbiased opinion — great at it. But unfortunately that old truism about it being hard to get published but even harder to stay published was in his case entirely true. Through no fault of his own, his publishing house went through a major restructuring, his editors left, and his books were largely abandoned.

That was life — and writing — lesson number one: the dream comes easily; the reality is paved with setbacks, a lot of hard work, and sometimes even having to put the dream itself up high on the shelf.

I’m sure it was hard — much harder than I was fully aware of as a child — for my dad to set his writing aside so that he could support our family. But he landed on his feet. He went back to law school, working the grueling hours of both a full-time job and a full-time course load.

But even still, he always made time for me — and he always had time for Sherlock Holmes. I think I was seven when my dad, reading to me at bedtime, read me the fateful opening of A Study In Scarlet — Chapter One: Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

From that moment on, Sherlock Holmes became my bedtime story reading of choice. I was captivated by the world of Victorian London: hansom cabs and cobblestone streets, gas lights and ladies in elegant, sweeping gowns. More than that, though, I was captivated by the figure of Sherlock Holmes himself: his staggering intellect, his almost magical ability to deduce the solution to a mystery from the scantiest of clues.

Of course, that’s hardly surprising; for more than a hundred years, since the first Holmes stories were published, millions of readers have been fascinated by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous consulting detective. The Guinness World Records lists him as the “most portrayed movie character” in history. The 1942 film Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror starring Basil Rathbone opens with the words:

Sherlock Holmes, the immortal character of fiction created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, is ageless, invincible and unchanging. In solving significant problems of the present day he remains – as ever – the supreme master of deductive reasoning.

Conan Doyle himself described Holmes as “a calculating machine,” and no one can read the Holmes stories without being aware that there is something more than slightly inhuman about Holmes, who declares in The Sign of Four, “Love is an emotional thing, and whatever is emotional is opposed to that true cold reason which I place above all things.”

Yet I think what fascinated me most about the great detective wasn’t the sense of almost alien otherness that many readers get from his character. Rather, it was an odd sense of familiarity — because for me, my dad was close to Sherlock Holmes. I don’t mean that he was cold or unfeeling or unaffectionate; he certainly was none of those. But being with my dad, I always had the sense of being in the company of an amazing intellect — I imagine in something of the same way Watson must have felt in the company of Holmes.

All the time I was growing up, I can’t remember my dad ever answering, “I don’t know,” to any question I asked. He could explain anything, from a question about algebra homework to one on Renaissance art — and he had Sherlock Holmes’ ability to be endlessly curious, endlessly interested in the world around him.

Thanks to my dad, I noticed the moments in the Holmes stories when the great detective shows a glimpse of humanity beneath the reason and logic. Moments such as when Dr. Watson is wounded by a bullet, and writes of Holmes’ frantic response:

It was worth a wound; it was worth many wounds; to know the depth of loyalty and love which lay behind that cold mask.

Or in The Adventure of the Cardboard Box, published in 1892, when Sherlock Holmes asks, “What is the object of this circle of misery and violence and fear? It must have a purpose, or else our universe has no meaning and that is unthinkable. But what purpose? That is humanity’s great problem, to which reason, so far, has no answer.”

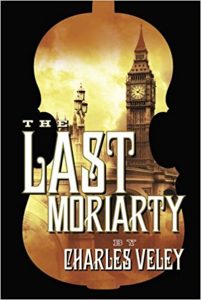

I was absolutely delighted when — after putting me through college and doing good work that mattered over the course of a successful career in real estate law — my dad felt inspired to write his own homage to the Sherlock Holmes character: The Last Moriarty, published by Thomas & Mercer in 2015.

Life and writing lesson number two: The seemingly fairy tale-esque success stories aren’t just fairy-tales. They do happen. Of course there are no guarantees, but at the end of the day, great things can happen if you keep your writer’s heart nourished and don’t give up on the dream.

I loved my dad’s unique take on the Sherlock Holmes character — which I think is built on absolute love and respect for the original Sherlock Holmes canon, and yet gives the reader a few more glimpses of that humanity hinted at in the Conan Doyle stories. In The Last Moriarty, Sherlock Holmes is confronted by a problem quite different from any he’s encountered in the course of his detecting career: a daughter. A headstrong, beautiful, and brilliantly intelligent daughter who challenges all his Victorian sensibilities about the rightful place of women and throws his cold, logically-ordered world into disarray.

I loved my dad’s unique take on the Sherlock Holmes character — which I think is built on absolute love and respect for the original Sherlock Holmes canon, and yet gives the reader a few more glimpses of that humanity hinted at in the Conan Doyle stories. In The Last Moriarty, Sherlock Holmes is confronted by a problem quite different from any he’s encountered in the course of his detecting career: a daughter. A headstrong, beautiful, and brilliantly intelligent daughter who challenges all his Victorian sensibilities about the rightful place of women and throws his cold, logically-ordered world into disarray.

In 2016, my dad asked me whether I would think about turning my own experience as an author of historical fiction to giving Lucy James — Holmes’ daughter — her own voice. The result was Remember, Remember, and I can truly say that writing it was one of the most fun, joyful, effortlessly delightful writing experiences of my whole career.

My father isn’t Sherlock Holmes, not really, and I’m not Lucy James. Yet it was tremendous fun for us both to not only dive into our shared love of Sherlock Holmes’ world, but also to write that father-daughter dynamic. To be a father-daughter team, writing about a father-daughter team. We’re separated by miles, living hours away from each other in different states, and by the inevitable busy-ness of my having a family now and three young children of my own. But writing with my dad still feels like coming full-circle, back to the magic of that first moment when he sat down next to me and read the unforgettable words:

Chapter One. Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

•••• •••• ••••• •••• ••••

Find Anna on Goodreads, Amazon, and her website.

Top photo: George Zucco as Professor Moriarty and Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes, in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

YouTube screen shot

Anna Elliott is co-author of the “Sherlock Holmes” & “Lucy Holmes Mystery Series.” She enjoys stories about strong women, and loves exploring the multitude of ways women can find their unique strengths. Anna lives in the Washington, DC area with her husband and three children.