Police Work: The breaking of an honest cop Chapter 2

Chapter 2

After my honorable discharge from the US Army in 1979, I had applied to and was accepted by the Herndon Police Department in Virginia.

Maybe I should have returned to New York City as my friend Larry did when he got out. He ended up becoming a police officer with the Port Authority Police of New York and New Jersey.

Had I returned to the city I probably would have ended up becoming an NYPD officer.

But that was not meant to be and life had other plans for me.

In 1980 shortly before I was accepted by the Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office in Virginia, I had a serious problem with a Herndon Police corporal.

I was investigating a series of burglaries. I had a possible suspect but not enough evidence against him at the time to get an arrest warrant.

So one day this corporal orders me to get a warrant for this guy. I tell him I didn’t have sufficient probable cause to get a warrant. He orders me to go to the magistrate and get one anyway, disregarding what I had just told him.

I went to the magistrate and told him that I was ordered to get the warrant.

Under oath, I tell him what I had. The magistrate refused to issue the warrant, which was the correct thing to do.

I go back and tell the corporal that the warrant wasn’t issued. The corporal tells me he was going to get the warrant himself and off he goes to the magistrate’s office with me following right behind him.

Under oath, the corporal fabricated some probable cause. He lied. I intervened and told the magistrate what the corporal had just stated was false. Long story short the magistrate refused to issue the warrant, and later initiated a complaint against the corporal with the chief magistrate.

What I got for doing that was hell. First from the sergeant, then the lieutenant then the chief of police. Even after explaining what had happened I was told that I should have done what my supervisor told me to do. That made no sense.

The corporal was later demoted back to officer. If that was not adding insult to injury. Lie under oath and still keep your badge. I wondered how many other times this corporal had lied under oath over the years just to make an arrest and or get a conviction.

Fast forward to 1984.

I am working as a criminal investigator with the Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office.

A murder trial was taking place in Fairfax County, Virginia, an adjoining county. The defendant was a Heckler and Koch firearms salesman. The prosecutor in the case was Fairfax County Commonwealth’s Attorney, Robert Horan.

One day a defense attorney and his investigator walked into our office and asked Investigator Bill Harris and me if we ever had contact with the victim. We did. The victim was not a nice guy. Neither were any of his friends. We had surveillance photographs of the victim and his friends.

They issued subpoenas and asked if we would testify as to what we knew about the victim. They were trying to prove that their client had killed the victim in self-defense.

We had no problem with that, after all any prosecution is about getting to the truth. Sometimes prosecutors forget that it is not their job to convict but to get to the truth of the matter.

That is what a trial is for.

The defendant was found not guilty by reason of self-defense.

When Bill and I were leaving the courthouse, Robert Horan came up to us and stated that he never saw anything like that, cops testifying for the defense. He said we had just gotten a murderer off. Bill looked at Horan and said, “He’s not a murderer he was found not guilty.”

Bill and I were later pulled into the sheriff’s office. Sheriff John Isom told us that “Fairfax” wanted us fired. He said we were responsible for Horan losing the case.

John Isom had been a captain with the Fairfax County Police Department before he retired and ran for sheriff of Loudoun County.

We never did get fired for that but I couldn’t help think why anyone in the criminal justice system would want us to get fired. I guess the prosecution would have been happier if we had just kept our mouths shut and not disclosed to the defense what we knew about the victim, even if that meant that all the facts would not have been presented at the trial.

Sometime after the trial, attorneys for the defendant wrote letters to the sheriff.

One letter read, “Deputies Harris and Poppa’s efforts at the trial and before-hand greatly aided the cause of justice. Their thoroughness and overall professionalism exemplified police work at its best, and was invaluable in ensuring the just result of the trial.”

Another letter read, “Deputies Harris and Poppa’s efforts were invaluable in ensuring the just result of the criminal trial. Both deputies were unselfish, demonstrated their expertise, and were tenacious in the search for truth. Deputies Harris and Poppa exemplified police work at its best. Too often work of this nature is considered routine, but Deputies Harris and Poppa demonstrated through their efforts what police officials have been striving for, for years: Professionalism.”

The father whose daughter was a witness to the shooting also wrote a letter to the sheriff that read, “… two of your deputies provided much of the missing links. Those deputies believed the oath they took when becoming law enforcement officers. They obviously believed that it is their duty to protect the innocent as well as convict those who are guilty. I understand that the commonwealth prosecutor was upset about your deputies telling what they knew to be the truth. Sheriff, you should be proud of Deputies Harris and Poppa. They deserve to be considered professionals. They are indeed true law enforcement officers.”

Robert Horan and I would cross paths again a few years down the road.

Working as a cop in Loudoun County was in stark contrast to the streets of Brooklyn where I grew up. The scenery was beautiful in the western end of the county, like something out of a picture postcard.

On the other hand, the county was predominately white.

Anyone who grows up in a large city has a broader understanding of people because you intermingle with people of all races. You learn that there are bad and good in all races and that no particular race of people has a monopoly on hatred, racism or criminality.

I believe that makes you a better cop.

Working undercover made me aware that not all criminals are violent bad guys. They may all be breaking the law but many of them weren’t necessarily violent people.

Selling drugs no matter how bad that was, to some was just another way of making money, it was just a business. On the other side of the coin were those who were so ruthless they would kill you in a second if they knew you were a cop. So I saw both sides of the criminal element.

What was so interesting about working undercover was that I was right there when the crime was being committed, you are actually part of it.

When you are working in an undercover capacity what you are actually doing is acting, you have an alias and a cover story. You become another character in your actions and your words. And each time you are with the bad guys your act has to be capable of winning an Academy Award, although no matter how good you may be, you will never win an Oscar; but if you fail to make a convincing performance you can end up hurt or dead.

Working undercover should be a prerequisite for working in any other type of investigatory assignment. Cops who worked undercover simply make better investigators in my opinion than those cops who did not.

Loudoun County had some firsts for me.

I never walked into a church in my life and saw a brass placard embedded into a church pew that read, ‘Donated by the Daughters of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,’ until a sergeant took me into a church in a town in the western end of the county one day.

It was also the first time I found myself testifying against a sheriff, in effect my boss, in a court of law. That was Donald Lacy, the sheriff who hired me before John Isom became sheriff. I had responded to an assault complaint one New Year’s Eve at the local Holiday Inn and it was the sheriff who was the suspect. The state police got involved and a few months later I was a witness in court.

It was also the first time I found myself testifying against a sheriff, in effect my boss, in a court of law. That was Donald Lacy, the sheriff who hired me before John Isom became sheriff. I had responded to an assault complaint one New Year’s Eve at the local Holiday Inn and it was the sheriff who was the suspect. The state police got involved and a few months later I was a witness in court.

Lacy had been accused by deputies of unauthorized absenteeism and sexual improprieties, allegations he denied. A special investigative grand jury recommended in 1982 that he resign, stating he had misused county funds, dropped criminal cases for friends and intimidated deputies. Lacy denied the charges, did not resign but in 1983 he did not seek re-election.

That must have been a bad omen for me of things to come down the road.

A sheriff and a commonwealth’s attorney are elected by the citizens of the county, they are politicians. They campaign which means they have supporters who donate money. Money leads to favors that can open the door for misconduct and corruption.

To me, the law is black and white. You are either right or you are wrong. Some don’t see it that way and say there is always a gray area.

In police work that gray area as far as I’m concerned, is known as corruption.

Politics should never mix law enforcement and the criminal justice system, however way too many times it does. It makes no difference if you are working for a big-city police department, a county sheriff’s office or a small-town police department.

I have seen plenty of instances where someone who has power, prestige, money and/or influence has received preferential treatment by the criminal justice system, while those who have little or no money seem to be treated differently.

And if you are poor the deck is already stacked against you in the criminal justice system.

Time and again we have seen how prosecutorial and police misconduct have sent innocent people to prison and later, sometimes many years later, they are exonerated because of an overzealous prosecution and or a shabby police investigation that was uncovered.

How do you give back someone years of their life that were lost in prison because of official misconduct by the police and/or the prosecutor?

Over a decade working in Loudoun County I saw my share of questionable occurrences. Things that happened that were just plain downright wrong. Events that made me question at times my faith in the system.

Some stand out in my mind to this day.

I arrested this guy one day for running a gambling operation. As it turned out he was a local businessman and a friend of the sheriff. I was at the county jail swearing out the affidavit for arrest in front of the magistrate, who then issued the warrant. In came the sheriff who tried to persuade me to drop the case telling me that it was just a case of gambling between friends. I told the sheriff what I had observed, showed him the seized cash, betting slips and odds sheet. He also talked to the magistrate with no luck.

The case was dropped by the commonwealth’s attorney the next day.

Several months later I am at the FBI Training Academy in Quantico, Virginia attending a sports bookmaking and numbers operations school. The agent teaching the class is the FBI’s top expert in the country on illegal gambling.

He asks if anyone in the class has made an arrest for illegal gambling. The next day I bring in the documentary evidence that I had kept, which consisted of the betting slips and odds sheet and explain to the class how the case went down.

The agent looks at the papers and remarks that it was a good case and asks what happened with it. I tell him the charge was dropped by the prosecutor.

He says if this case was dropped you have a real serious problem in Loudoun.

That would be the understatement of the decade!

I had arrested a local bank president and business owner for soliciting prostitution. We had the female informant wired up and he implicated himself on the tape. He asks the female if she had any friends who would like to make some money as he holds parties for some influential people in the county and names some local politicians and attorneys who attend these parties.

That was another case that went nowhere. In general district court, it was all whispers at the bench between the judge, the defendant, his attorney and one of the assistant commonwealth’s attorney. They deferred the finding for a few months and then dropped the charge.

In another case, I had arrested two female gypsies for felony fraud on a Friday. They had no identification and the identifiers they gave were fictitious. They were booked into the county jail to remain until Monday morning when they would be taken to court. After I made the arrests the dispatcher transferred a call to me from some guy who wanted to get them out of jail. I told him they would not be released and he asked if he could give some money to get them out and he wasn’t talking about bonding them out if you get my drift.

Sunday afternoon I received a phone call from the jail telling me that a general district court judge had come to the jail with some guy and the girls were released. We never saw the females again. When the prints came back from the FBI we discovered they both had lengthy arrests records and one was wanted in another state.

I didn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out what probably happened.

The evidence custodian for the sheriff’s office tells me one day that none of the narcotics evidence that he takes to the court for the trials is ever returned to him. He says sometimes nobody even signs for it when he takes it over to the court. He shows me the chain of custody forms that indicate that the evidence is still in the evidence room. It’s not. He says he was told it’s in the safe at the clerk’s office.

The state code mandated that seized narcotics must be destroyed by the seizing agency, the sheriff’s office. The evidence custodian was told that a deputy clerk of the court burns the drugs in an incinerator in the western end of the county with one of his friends.

After hearing all this bullshit I go and speak to the sheriff who tells me to mind my own business that he talked to the clerk of the court and everything is okay. Another investigator had similar concerns and also talked to the sheriff and got the same answer.

Whether that evidence went up somebody’s nose or hit the streets again who knows.

Years before, $5,000 cash that was evidence in a criminal case came up missing from the clerk’s office. That money was never recovered.

Another narcotics investigator from the department told me that the sheriff had told him that he knew somebody that was inside a house outside of Leesburg, Virginia and that this person had seen a table in one of the rooms that was filled with $100 bills stacked to the ceiling.

The investigator who was assigned to a federal DEA drug task force had asked the sheriff for the name of that person because it was pertinent to an ongoing investigation of the owner of the property. I was told the sheriff refused.

I remember this officer telling me that he had to write all this up in a DEA report and that it was making him look bad because the sheriff would not cooperate and tell him who was in the house.

Years later, a high ranking member of the sheriff’s office at the time told me that it was the sheriff himself who saw the cash in the house.

What the sheriff was doing in the house of a major drug importer of hashish and marijuana was never known.

In 1985 a federal grand jury indicted 26 persons in the Virginia-based, $100 million, coast-to-coast drug trafficking ring. Later police would find bags of cash and jewelry buried all over this guy’s property. He pleaded guilty to running a continuing criminal enterprise and was sentenced to federal prison.

It wasn’t only drug evidence that was missing from the evidence room.

There were allegations that other seized evidence was at the homes of high-ranking sheriff’s office officials.

We needed equipment in the narcotics unit. We were told that it wasn’t in the budget, however, there was almost a quarter of a million dollars in the asset forfeiture fund that remained untouched for reasons we never knew.

Things had been stinking in the woodpile in Loudoun County for many years and it was a lot more than just missing evidence.

The lid was about to be blown off of law enforcement and the criminal justice system itself in Loudoun County.

And the shrapnel from that explosion would come heading straight at me, ripping apart my character, reputation and finally my career.

What they didn’t count on though was a Brooklyn born outsider that wouldn’t back down.

I had the greatest weapon of all on my side; the truth.

Chapter 3 is next. Chapter 1 here

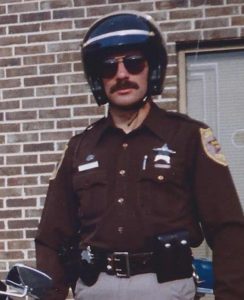

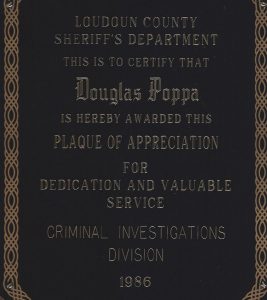

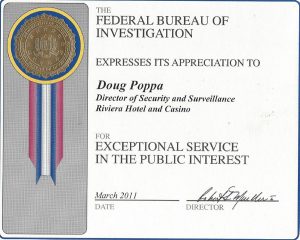

Doug authored over 135 articles on the October 1, 2017 Las Vegas Massacre, more than any other single journalist in the country. He investigates stories on corruption, law enforcement and crime. Doug is a US Army Military Police Veteran, former police officer, deputy sheriff and criminal investigator. Doug spent 20 years in the hotel/casino industry as an investigator and then as Director of Security and Surveillance. He also spent a short time with the US Dept. of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration. In 1986 Doug was awarded Criminal Investigator of the Year by the Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office in Virginia for his undercover work in narcotics enforcement. In 1992 and 1993 Doug testified in court that a sheriff’s office official and the county prosecutor withheld exculpatory evidence during the 1988 trial of a man accused of the attempted murder of his wife. Doug’s testimony led to a judge’s decision to order the release of the man from prison in 1992 and awarded him a new trial, in which he was later acquitted. As a result of Doug breaking the police “blue wall of silence,” he was fired by the county sheriff. His story was featured on Inside Edition, Current Affair and CBS News’ “Street Stories with Ed Bradley”. In 1992 after losing his job, at the request of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Doug infiltrated a group of men who were plotting the kidnapping of a Dupont fortune heir and his wife. Doug has been a guest on national television and radio programs speaking on the stories he now writes as an investigative journalist.

Doug Poppa is one of the biggest heroes that has ever been in law enforcement. The law enforcement he speaks of is why every single member of law enforcement today is nothing but a criminal at large.