Frank Serpico sets the record straight, Part 6

Editor’s Note: Read the complete series on Frank Serpico under Special Reports.

Butch and Sundance New York Style

This is the untold story, that Durk, before I was shot, was planning to make a movie. It was going to be, Durk said to me, look Serpico, don’t think this movie is about you. You’re just one of the characters. I said really, I’m just one of the characters. So, one night he said we’re going to have dinner tonight with Paul Newman. I said really. I mean how the hell does he get ahold of Paul Newman. I said right, so I go to dinner, they sent a car to pick us up. I meet Paul, he’s a nice guy. I met his wife, Joanne (Woodward). After dinner, when we leave, Durk said to me, why did you tell him the whole story, so now, he doesn’t need us anymore? I said how are they going to tell my story If I don’t sign a contract.

One night I call Durk, and I think this guy’s name was John Foreman, a movie producer and I hear their going to do a movie. Paul Newman is going to play Durk, and Robert Redford is going to play me. I go wow, that’s interesting.

So, one day I’m having tea at the Russian Tea Room in New York, a big venue for the hobnobbing literary agents, and their talking. I said, oh let me see, you plan on making a movie like Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid. They all nodded, yeah. I said so you saw the movie, they said yeah, of course. I said remember when Butch Cassidy jumped off the cliff, he was holding the Sundance Kid’s hand or something. They said yeah. I said they jumped. I jump alone and I stood up and walked out.

The agent, Sam Cohn, one of the biggest in the country, comes running after me. He said Frank, you just blew six-hundred grand. I said, I could have made more than that as a crooked cop. He said to me, boy you sure have your principles. I said isn’t that what it’s all about.

Frank, why didn’t you want to do the movie?

I never worked a day with David Durk, he was not my partner. They wanted to do Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, New York style. The deal fell through. After I got shot, The Viking Press said they would publish what I wrote. I wrote the first two chapters, then they got Peter Maas to write the book.

It’s Blackjack’s case

In Edward Conlon’s book Blue Blood, Conlon writes that he was not in favor of Frank taking a perp out for coffee because he saw it as an opportunity for the guy to throw a cup of coffee into Serpico’ eyes or escaping to Florida. I asked Frank about that.

I had arrested a guy for kidnapping and raping a woman. I got his accomplices by sweet-talking him to turning in his buddies. The night before the detectives had beat the hell out of him and got nothing from him. When we were taking him into the wagon to be transported, I said I will take him in my own car.

I brought him coffee at the café around the corner from the police station. You do what you do when you know how to talk to get information. I told him that he was the one who got caught. He ended up giving me the names of the guys he was with. I told him that I would tell the DA that he cooperated and I did tell the DA that.

After getting that information, I called the detectives. I told them that I knew where the suspects were. They told me that they didn’t want to do anything because it was Blackjack’s case and he was off. I went and grabbed them myself. The detectives then stole the collar from me.

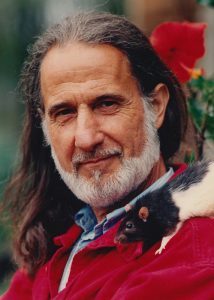

Conlon called Frank a very strange man in his book and wrote about a mouse scrambling around his shirt collar.

I guess he thought I was half crazy before I was shot because I had brought a mouse to work. It was an undercover tactic. Who would ever think on the street that a guy who looked like me with a mouse would be a cop.

There was an article about this book and I commented on it. I said he wrote that his great-grandfather was an NYPD cop who was also a bagman and that he thought that was a novelty. He also called corruption, corrosion. I said is that the Harvard word for corruption.

Some captain put his two-cents in and said that he never saw corruption in the NYPD and that I should be ashamed of myself. This guy was a captain and never saw corruption. What did he have, his head up his ass.

Deputy Chief Inspector Paul Delise

In August 2006 Paul Delise passed away at age 86.

His daughter wrote at the time,“My father worked as a police officer for New York City. He retired after 30 years of service. He made a lot of good friends and a few enemies. His good friends were those who were honest, like him. His enemies were those who were dishonest and corrupt. He achieved some notoriety in the latter part of his career by helping fellow officer, Frank Serpico, expose the corruption on the force to the New York Times. I never really saw my father as a policeman. I saw him as a funny guy, an artist, a philosopher, and a romantic who use to like to sing like Mario Lanza at the top of his voice while driving down the Cross-Bronx Expressway. Someone recently referred to my father as a legend … I know he leaves behind a legacy to which we were all proud.”

Frank Serpico also wrote. “A better friend and partner an honest cop could not wish for. The only retirement gift I received from the whole NYPD was from Paul in his usual funny way. A money clip with a detective shield and the inscription; “To Frank a good cop and a good friend.” I say ditto to you Paul, I know you are in good company with all the other good saints. Without you, it would have never happened.”

Frank talked about the importance of Paul Delise.

I got assigned to the patrol borough of Manhattan North. There was one good guy, they called him Saint Paul. That was Inspector Paul Delise. Doug, did you ever hear of a cop working with a full inspector as a partner? We couldn’t trust anybody in the borough, so that tells you how rotten it was. We were on roofs, in alleys, in basements, communicating with walkie-talkies and making cases.

Let me say this Doug. Durk even wanted credit for Delise going to the New York Times. I remember it as if it was last night. I was in Delise’s house. I said to him, boss, I must go to the New York Times, you know if they set me up, I’m finished. He said Frank, I remember this, his kids were running around the house. He said I haven’t paid my mortgage, this is all I know, this job. I’ve been a cop all my life. He said you do what you must do and I’ll back you 100 percent. He went with us to the New York Times, because if it wasn’t for Paul, our word wouldn’t have meant crap. That was a man of honor. If it weren’t for Inspector Delise, nothing would have happened.

Dave Burnham from the New York Times

If it wasn’t for Dave Burnham of the New York Times the story never would have happened. I always said to Dave Burnham’s credit, because everybody said that if it wasn’t for this guy or that guy, like Durk wanted to say if it wasn’t for him. I tell everybody, if it weren’t for Dave Burnham this story never would have happened. That was one. The second guy, if it wasn’t for him it would never have happened and that was Chief Inspector, Paul Delise.

Antonino interviews Dave in the documentary and Dave Burnham tells the story himself. I gave Antonino all this information, my video’s, pictures and contacts. I thought let him do the documentary, and this way I’ll be around to see what he does. He did do a pretty good job.

Now, what Dave Burnham did, he wrote the story but at first, his editor wouldn’t let him publish it because it was talking about corruption in the New York City Police Department. So, Dave told the story of corruption to Mayor Lindsey’s aid but didn’t tell him at the time it was about the NYPD. He talks about it in the documentary. He pulled a smart move. Lindsey’s aid never called him back. Dave finally calls him and said, remember that corruption I was talking about, it’s the New York City Police Department.

So, Lindsey, to cover his ass right away forms the Rankin Committee. But Lindsey puts the police commissioner, Leary, and the District Attorney on this committee. All the people that were involved. Ed Koch, a congressman at that time, who later ran for mayor and became mayor, and I objected. We said how can the police investigate themselves. Lindsey got embarrassed and right away he terminated that committee and appointed the Knapp Commission, but he gave them limited time and budget.

One night there was a big burglary at the meat market in Greenwich Village which was a couple of blocks from my house. I happen to be walking by. I called up one of the Knapp Commission investigators and he came by. They caught the cops. So now they had something to sink their teeth into.

Here’s another thing. This is just me giving you my opinion. You know who William Phillips was right?

He was one of the corrupt cops who testified at the Knapp Commission.

Now Phillips, they got him for the murder of a prostitute and a pimp. You’re New York’s finest, don’t tell me that this guy was so cool that you couldn’t get him. You know how they got him? When he testified at the Knapp Commission. Then suddenly, oh, somebody recognized him. It was payback time, they never would have touched him and he did some time.

In fact, it was corrupt cop Phillips who corroborated what Frank had been saying about the corruption in the plainclothes units. Michael Armstrong, who was the chief counsel to the Knapp Commission, wrote in his book, They Wished They Were Honest, that the activities of the NYPD’s 450 plainclothesmen, which had been the subject of Frank Serpico’s initial revelations, were of interest to the Knapp Commission. They wanted to know if Serpico was accurate in describing the organized corruption in the plainclothes units to which he had been assigned, and did such corruption exist in other plainclothes units.

Armstrong wrote that according to Phillips, it was common knowledge that all plainclothesmen were corrupt. The graft was so well organized, no one could serve in a plainclothes unit without participating.

Phillips testimony before the Knapp Commission was corroborated by recordings of conversations he had made with other corrupt cops after he was wired by Knapp Commission investigators and went undercover for them.

Frank, who went to the New York Times with you?

David Durk, Paul Delise and a friend of Durk, a sergeant who didn’t want to be named.

In the 1996 book Crusader by James Lardner, the author writes that six police officers in all went to the New York Times: Durk, Delise, Serpico and three others, a captain, a lieutenant and a detective, who Lardner writes, have yet to come out of the closet.

Edward Conlon, in his 2004 book Blue Blood also writes that three others, still-anonymous cops also went to the Times.

I asked Frank if he could elaborate on that.

I gave all the information I had to the Times. Paul Delise was right there next to me, the other guy was David Durk and one sergeant, who was a friend of Durk. He had nothing of substance to add.

Doug, when you told me that I called Dave Burnham. I just got off the phone with him. There was no captain or lieutenant which I knew, because like I said, I was there.

After the premier of the documentary at the Tribeca Film Festival they held a little party for the crew and participants. I invited Corey Kilgannon from the New York Times and Larry McShane from the New York Daily News, that I have known for years. We were sitting at my table and Dave Burnham was also there. I didn’t realize what a treat it was for those guys, looking up at Burnham, their predecessor. This old guy who had broken this big police corruption story in the New York Times. It was nice to watch, and Dave enjoyed it to.

Dave Burnham speaks

Dave Burnham, after almost ten years of writing about the NYPD, left that beat and wrote two investigative books. One on the IRS and the other on the Justice Department. He said, “So I wasn’t just picking on the poor old NYPD.”

When I told Dave that I was writing a story on Frank he was more than willing to talk to me. I asked him how the story came about. The biggest story in the country at that time on police corruption.

Here was my problem. The editors, both editors and the editorial editors and the city were high on Mayor Lindsey, they all thought that he was terrific. I thought he was stupid and naïve, but a beautiful man.

I sought very hard to develop information that would allow me to present my feelings, Serpico’s feelings, and Delise’s feelings, that this was a citywide problem. Not from one individual cop. Newspapers were full of stories about individual cops. I wanted to do something else. So, I took a lot of steps and one of them was to, I don’t remember if it was my engineering or Frank’s or what, anyway we managed to get a bunch of people to come in and persuade Arthur Gelb [the metropolitan editor] and [Abe] Rosenthal [managing editor] that this is a bigger problem. This is not a story of an individual cop who took money, this is systematic and there were problems in how the system worked.

To do that having Frank, Delise and Durk, who was then well regarded, in to talk was useful. My motive was to try to persuade the [NY] Times that this is a systematic problem, to have them come in and spend, I don’t know, three or four hours talking about their experiences. And as Frank says the sergeant didn’t have any really big experience. That wasn’t the point. The point was to not have it as the story of one individual crooked cop, and that was the purpose of it.

I had done a lot of reporting. There was a cop in SIU who’s name I can’t remember at this moment, who was in the news some, and he was talking to me. He didn’t want to be quoted. He was talking to me about everything that was going on. There had been an SIU guy that had gotten involved in a shooting. This guy in SIU pointed this out to me. The district attorney in the Bronx got interested in it.

So, there was lots of other evidence and I had interviewed scores, maybe dozens, maybe a few hundred people in this period that I worked on this.

When I came to the Times I had adopted the idea this was not what the paper was thinking about. I decided that what I want to do was present evidence about how the agency I am looking at whether it’s the district attorneys, the judges or whatever were not achieving their stated goals. I took the stated goals of the NYPD. They’re supposed to be protecting the public and they weren’t and that’s what I wanted to do.

I had caught Serpico’s attention on my “cooping story.” [On Dec. 16, 1968 Dave wrote a story that ran on the front page of the New York Times alleging that large numbers of NYPD officers were “cooping” meaning sleeping on the job.] Howard Leary, the police commissioner then yelled and screamed. That wasn’t aimed at an individual. I was saying that the department didn’t care about this. That deprives the public of patrol.

I think that’s why Frank, Delise and all of them said, he’s a straight shooter. So that’s essentially my pitch.

Knapp was a terrific guy. Knapp was a great story. He was an upper-class guy. After some thought he finally went after Lindsey, because of Jay Kriegel, his assistant, who was a jerk.

New York City had a lot of problems. Crooked cops, the city council of New York was crooked. They withdrew money from Knapp and refused to fund him. It was a wonderful story to work on.

I got death threats too. From the police and the district attorney’s staff. They called up and said we’re going to kill your child. When that happened, I talked to [Chief] Sid Cooper. I called Cooper, a cop I really trusted and I said what do we do?

He said listen kid you never worry about the death threats you get. It’s those you don’t get that you worry about. I talked to my wife, then wife, she thought about it. That makes sense. We didn’t run, we stayed there. We were literally putting our children’s lives at stake here. That happened.

Cooper was a wonderful guy. Sid and I went to the hospital when Frank got shot. That was later in the day and we talked to him.

Doug authored over 135 articles on the October 1, 2017 Las Vegas Massacre, more than any other single journalist in the country. He investigates stories on corruption, law enforcement and crime. Doug is a US Army Military Police Veteran, former police officer, deputy sheriff and criminal investigator. Doug spent 20 years in the hotel/casino industry as an investigator and then as Director of Security and Surveillance. He also spent a short time with the US Dept. of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration. In 1986 Doug was awarded Criminal Investigator of the Year by the Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office in Virginia for his undercover work in narcotics enforcement. In 1992 and 1993 Doug testified in court that a sheriff’s office official and the county prosecutor withheld exculpatory evidence during the 1988 trial of a man accused of the attempted murder of his wife. Doug’s testimony led to a judge’s decision to order the release of the man from prison in 1992 and awarded him a new trial, in which he was later acquitted. As a result of Doug breaking the police “blue wall of silence,” he was fired by the county sheriff. His story was featured on Inside Edition, Current Affair and CBS News’ “Street Stories with Ed Bradley”. In 1992 after losing his job, at the request of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Doug infiltrated a group of men who were plotting the kidnapping of a Dupont fortune heir and his wife. Doug has been a guest on national television and radio programs speaking on the stories he now writes as an investigative journalist.