Father’s Day offers poignant reminder of fathers lost in war

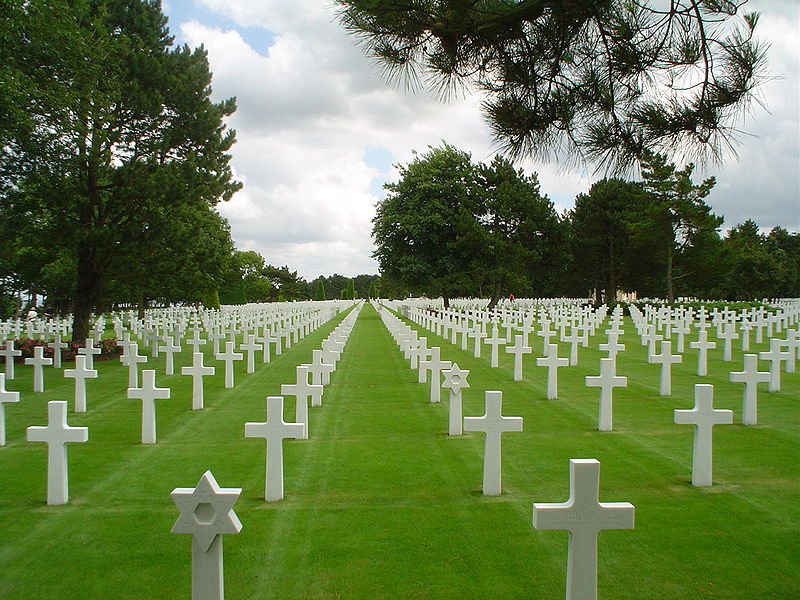

Edward A. Peters III is proud of the portrait which shows him on the lap of his uniformed father – a U.S. Army captain – as his grandfather augustly looks on. But what Peters knows of his father’s wartime service comes mostly from his own research. Captain Edward A. Peters died on D-Day – June 6, 1944.

Now in his seventies, the younger Peters is a member of a support group called the American World War II Orphans Network. This reporter spoke with Peters, and fellow network member Stewart “Rusty” Lerch, at this year’s Mid-Atlantic Air Museum World War II Weekend.

“I grew up on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where my mother lived; that’s where she met my father. After he was killed, we eventually moved to Florida,” said Peters.

“I think, at first, you just kind of push (your father’s death) away and don’t deal with it. I had never really talked to anybody else who’d lost their father; it wasn’t something I’d paid a lot of attention to. But I found, in my 50’s, I started to get interested in my father and what happened to him. When I discovered this group, I found that a lot of people were like me. Maybe it was as our children got older that we turned our attention to other things, and one of them was, what happened to my dad? What was he like? And all that.

“I was lucky; in my research, I found a lot about him. He was a company commander of a regimental headquarters company, so his immediate superior was the colonel of the regiment. When the colonel was reported on, my father was there. So his name was in a number of places. It was recorded in the logs when he was killed.

“He was killed on D-Day. They landed about one o’clock, and he was killed about 2:00 in the afternoon. He was leading a patrol out to find out where the Germans were, and they found them. A few years ago, I met the man who was next to him when he was killed. I can’t remember his name at the moment. He was a farmer in Texas, but he’s passed away now. It was very emotional meeting him and getting a description of exactly what happened when my father was killed. But I was glad to do that. You know, you try to find out what you can, and of course, in the end, there’s still something missing. You know what I mean? You never find him, because he’s gone. I was 10 months old when my father was killed.”

As a fellow Marylander, this reporter wondered if Peters’ father was in the 29th Division which landed with heavy casualties on Omaha Beach on D-Day.

“He was actually in the 101st Airborne, so he parachuted into Normandy,” said Peters. “I’m not sure why he went into the paratroopers. He was a special services officer, but he wanted a line command. I don’t know how he did it, but he found that there was an opening in the 101st Airborne for a company commander, and got transferred there. Something that made me angry at first, when I heard about how hard he worked to get into a position of danger like that. You know, I mean, that’s just the man he was. He would have been somebody else if he didn’t do it that way.”

My Baby Will Know Their Story

Our conversation with Peters was interrupted briefly by expectant mother, Elizabeth Aronson. A Philadelphia resident, Aronson said she attends the World War II Weekend specifically to thank the vets.

“I’m the grandchild of Holocaust survivors, and I was just thanking Mr. Peters for his father’s service,” said Aronson. “If it weren’t for men like him, who saved my family, I wouldn’t be standing here. I’m 5½ months pregnant, so this will be a 4th generation survivor on it’s way. I just wanted him to know that I’m sorry for the loss of his dad, but I’m grateful for his father’s service.

Aronson said it really troubles her that people of her generation don’t remember the sacrifices of World War II vets.

“They see war now as this far and distant thing. World War II was the last time we had war on the home front, and they need to understand what these guys went through; how many people lost their families, and how many people lost their fathers. When I was growing up, in 4th or 5th grade, there was a paragraph in my Social Studies book and that was all they talked about the Holocaust. One single paragraph.

“People need to remember.

“I was just talking to a survivor of the Battle of the Bulge, and he said, ‘Please make sure that your unborn daughter knows’. I promised him I would tell my baby their story. The World War II vets today are frightened – just like Holocaust survivors are frightened – that when they are gone, no one is going to remember.”

A Widow At 22

Seated next to Peters was Stewart “Rusty” Lerch of Reading, Pennsylvania. Lerch serves as the group’s point man for the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum World War II Weekend.

“I first met this group here at the airport, and now I’m the contact person for this event. I will get the passes for the group, make sure we have a table and a spot in the hangar. I will also make sure that everybody who comes in knows where they need to be. Normally, we have 4 or 5 different individuals that come by to help and work the tables. We’re not here to sell anything. We’re just here to see if we can find other WWII orphans, or any family member that is interested in information about their loved one that may have served in the Second World War.

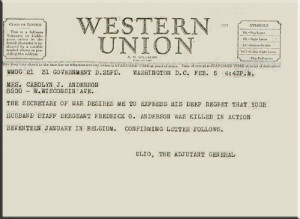

When asked about his own story, Lerch replied, “My story is sort of simple. I think my mother put it the right way. My mother always said she was a bride at 20, a mother at 21, and a widow at 22. My dad was 23 years old when he was killed; I was seven months old. I have no memories of him.

“My dad served with the 27th Engineer Combat Battalion in the Southwest Pacific and was killed on the island of New Guinea. He’s buried over in Manila. My dad was one of twelve children; he came from a large family. As a young child growing up, I would ask about my dad. They would just say, ‘He’s a hero’.

“As a young boy, I would walk into a room and people would stop talking. We orphans call it The Wall of Silence. It was hard to find out information until years later. I met a geography teacher, named Mr. Jones, at Northeast Junior High School in Reading, who served as a naval officer during the Second World War.

“I was in 7th grade, and he saw me looking at a map of the world, and he asked what I was doing. This was right before class, and I told him my story. My dad was killed in New Guinea, but I have no idea where New Guinea is. He’s buried in Manila; I have no idea where Manila is. Mr Jones took the time to explain how the war was fought, with Admiral Nimitz and the Marines through the Central Pacific and General MacArthur and the Army through the Southwest Pacific. He took the time to show me what I needed to know, and he said, ‘Don’t ever stop learning about your dad or asking questions about what happened.’ I haven’t.

“I’m still learning every day about my dad, things that I didn’t know. My dad did have the opportunity to see me when I was in the hospital after I was born. He had a five-day pass and then an emergency pass, I think they called it, which extended his leave another five days. That is the last time he was home. He shipped out and never came home again.

“Growing up, I was always interested in history. I started to get involved in various military organizations. The only way I could learn about my dad was to talk to veterans. Veterans had a hard time talking until they heard my story, and then they would fill me in on some of the details. Still learning today, still talking to people.

“I really like talking to students about WWII and about growing up as an orphan. People will sometimes say, ‘Well, you weren’t an orphan – you had your mother’, but they have to realize our fathers were killed in action, and our mothers were going through a very traumatic time in their lives. It was extremely difficult for them. My mother never remarried. She passed away a year ago; she was 92. The hardest time of the year was always Christmas for her. Christmases were hard for all of us. As a child, I would receive a baseball glove, a football, but there was nobody to play catch with.

“One year, I got the ultimate Christmas gift: a Red Ryder Daisy BB Gun. I was 11 years old. I took it downstairs in the basement; we lived in a row home. I put my target up on what they would call the coal bin. I shot at my target, and I shot my grandmother’s windows out of the front of the house. Needless to say, that Christmas, everybody talked to me.”

Lerch noted that his father was killed May 31, 1944. Because of the time difference, it still would have been Memorial Day in the United States.

“Remember, the reason that we can celebrate today is those who gave their lives. Once in a while, I will be a guest speaker for Memorial Day services. I usually end my talks by saying something very simple, like, ‘My father, along with all the other brave men and women who gave their lives for our country; they are not gone, they are not dead, they are still with us. They live today. You can hear their voice in the Declaration of Independence, and they live in the freedoms that you and I enjoy each and every day of our lives.’”

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”