Baltimore Post-Examiner goes ‘Back to the Future’ with a nod to Charles Dickens

The first volume of Bentley’s Miscellany—a 636-page literary publication printed in London in 1837—comprised a collection of short stories, poems, plays, lyrics, historical accounts, and illustrations from writers and artists across England.

In an address to readers, the publication’s editor wrote:

“We have produced a great variety of novelties, some of which we humbly hope may become stock pieces, and all of which we may venture to say have been most successful … We shall open our Second Volume, ladies and gentlemen, on the first day of July, One thousand eight hundred and thirty-seven, when we shall have the pleasure of submitting a great variety of entirely new pieces for your judgment and approval.”

The editor signed the note “BOZ”—a nickname used as a pseudonym by then-25-year-old Charles Dickens.

“The [publication’s] management will again be confided … to the humble individual with the short name, who has now the honour to address you, and who hopes, for many years to come, to appear before you in the same capacity,” Dickens wrote.

Dickens held editorial control over Bentley’s Miscellany for only two more years, but it was also where he first serialized his social novel, Oliver Twist, from February 1837 through April 1839.

In the 19th century, it was common for Dickens and other novelists to serialize their works in newspapers and magazines, writing and publishing several chapters at a time in a weekly or monthly publication. In the United States, the works of Edgar Allen Poe and Mark Twain were similarly published in newspapers and magazines.

If you visited the Newseum in Washington, D.C., you would see these publications were not as we know them today—they weren’t chock full of hard news and photos, analysis, feature-writing, opinion, and crossword and Sudoku puzzles. The organization’s News Corp. News History Gallery displays several examples of fiction in newspapers, including Twain’s The Gilded Age appearing in Oregon’s Bedrock Democrat, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin serialized in The National Era, a weekly abolitionist newspaper, according to Rick Mastroianni, the Newseum library manager.

“Those are two examples of fiction in 19th century newspapers,” Mastroianni said. “The timeline of our News History Gallery starts in 1455 with the advent of the printing press. We have artifacts on display that date back to the 1500s.”

Nineteenth-century newspapers and magazines were literary “grab bags,” says Christopher Daly, a veteran journalist who wrote for the Associated Press and the Washington Post.

“There is a long tradition in American journalism of struggling to fill the space,” said Daly, a journalism professor at Boston University who recently finished his book, Covering America: A Narrative History of U.S. Journalism.

“Anyone who’s ever run a newspaper or a magazine is familiar with this problem,” Daly said. “Figuring out how to fill those pages.”

Filling the news hole

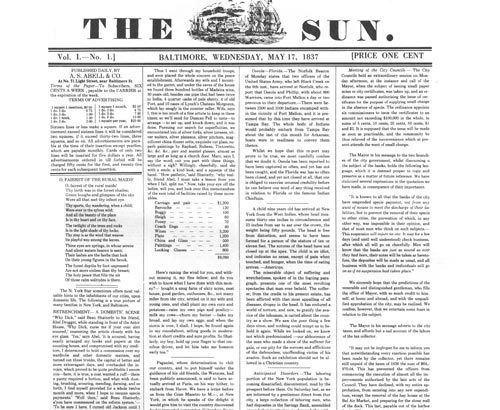

Editors “struggled to fill the space” for two reasons: visual journalism with photography was not at the time technically possible, and newspapers did not yet employ full-time reporters to write news stories. Most newspapers and magazines were filled with only text and small headlines; in fact, the Baltimore Sun recently celebrated its 175th anniversary and posted on its website an image of its first front page from May 17, 1837. The page was essentially a black block of tiny text under the Sun masthead.

“Editors of newspapers would fill them with all sorts of things,” Daly said, mentioning sayings, jokes, poetry, and long- and short-form fiction. “You wouldn’t know what you were coming across, and that was one of the great things about reading these papers.”

“Editors of newspapers would fill them with all sorts of things,” Daly said, mentioning sayings, jokes, poetry, and long- and short-form fiction. “You wouldn’t know what you were coming across, and that was one of the great things about reading these papers.”

Serialized fiction is today more prevalent online, but in 1999, readers of several New York Times Regional Group newspapers came across Ain’t Done Yet, a newspaper novel by the Poynter Institute’s Roy Peter Clark. With 29 quick-read chapters (a little more than 1,000 words per chapter), the story followed a St. Petersburg, Fla.-based investigative reporter’s pursuit of a doomsday cult with disastrous plans for the turn of the century.

The newspapers printed a chapter every day. While readers eagerly awaited the next installment, the paper’s writers and editors had varied reactions to mixing fantasy and reality in their pages. Some were happy to draw readers to their publication, while others questioned the story taking up space that could go to hard news.

Clark, Poynter’s vice president, at the time, said, “If there is a situation where the news hole is too small for the news that is being written about, then of course, don’t run the fiction novel. But there’s nothing inherently wrong with the coexistence of nonfiction and fiction that is labeled as such.”

Shifting the Focus

The shift from Dickens-era newspaper content occurred in the late-19th and early 20th centuries, as big-city papers in America became profitable and competition grew as there began to be more newspapers in every city (New York City was home to 17 English-language daily newspapers in 1920).

The point on which these papers competed was on their coverage of local politics, crime, business, and sports, Daly said. The addition of large photographs and advertisements left little room for items such as short stories, poems, or lyrics.

“What gets squeezed out, going forward for newspapers, is this unclassifiable, literary material,” Daly said.

It has been well documented, but traditional print newspapers have lost the battle to online publications in the last decade. Almost everyone today carries a smartphone and has a Twitter or Facebook account, or both, making access to news faster and easier than ever. News websites saw their audience grow by 17 percent in 2011, while newspaper and magazine readership declined by 4.5 percent, according to the Pew Research Center.

As further proof of this news evolution, in April, the Newseum opened the HP New Media Gallery, an innovative exhibit that explores social media’s growing role in journalism. The gallery features several interactive experiences and a multi-screen video presentation that illustrates the progression of global media.

“This new exhibit talks about the impact of new media from the news-reporting side, and how it has changed the way people gather and disseminate news,” the Newseum’s Mastroianni said. “It focuses on the story of the digital news media.”

The issue for web publications, though, Daly said, appears to be too much topic specialization. There exist numerous lyrics and song websites, poetry websites, historical fiction websites, but where do we find sites that harken back to the days of Dickens and Bentley’s Miscellany?

“Audiences expect to go deep into a single, specific specialty on the web,” Daly said. “What’s lost in that dynamic is the experience of serendipity, picking up a generalized vehicle that’s going to surprise you.”

Surprising the Reader

Several journalists who worked for newspapers in Maryland and Washington, D.C., want to surprise readers of their new website, Baltimore Post-Examiner. The site, which launched in April 2012, is not a typical news source, and it hopes to be anything but typical.

Where you’ll find news and blogs, you’ll also find that literary “grab bag” of fiction, poems, music, and humor, said Timothy Maier, one of Baltimore Post-Examiner’s founders and a veteran journalist who served as the managing editor of the defunct Baltimore Examiner from 2006 to 2009.

Maier and his co-founders, some who had endured newspaper layoffs, asked the question: What’s next in journalism?

“I wanted to bring back a little old-school to the new school of journalism. I grew up reading the Green Sheet (a special entertainment section in the Milwaukee Journal), which included all kinds of different writing on literally a green sheet of newspaper,” Maier said. “I thought it would be a fun idea to showcase all types of writing.”

Maier studied news sites, those that had thrived and those that had failed, and he learned the ones that failed shared similar qualities. They were too local or too specialized to sustain and build readership, which is necessary to attract advertisers and generate revenue.

“We came to the conclusion that to make it, we couldn’t be a niche site about Baltimore, or crime or sports,” Maier said. “We needed to be a little bit of everything.”

Maier and the site’s co-founders have been in journalism for many years, equipped with connections to talented writers and artists across the world. On a random mid-week day, Baltimore Post-Examiner published a news story on an economic forum in Kazakhstan, a feature on a Bangladeshi sitar player in Washington, and a blog post defending Batman as the world’s greatest superhero.

Readership has increased more than Maier expected. “I’m stunned at times to look at the site metrics reports and see that people are spending several minutes on a short poem, as well as several minutes reading exclusive serial novels or our longer news features.”

That element of exposing readers to new genres, leading them to new discoveries as Charles Dickens did as “BOZ” nearly 200 years ago, keeps journalism alive, said Elliot King, a communication professor at Loyola University Maryland and author of Free for All: The Internet’s Transformation of Journalism.

“Those early newspapers in the 19th century were run by an eclectic, salon-like group of intellectuals,” King said. “That edge has always been there in journalism, but it got drummed out in newspapers, which over time became too rigid, narrow, and formulaic.”

Newspapers, now morphing into online content hubs with distinct voices and personalities, can sharpen what had become a dull edge, King said.

“I always said that newspapers would survive because they offered the reader that sense of discovery, but you can have that same type of discovery online,” King added. “Everyone on the web is broadening journalism and saying, ‘Let’s try other stuff.’”

Andrew Cannarsa has been writing professionally for almost 10 years, first as a crime and safety reporter at a community daily newspaper outside Philadelphia, and then as a business reporter at Baltimore Examiner. He graduated with a journalism degree from Boston University in 2005. Follow him on Twitter @cannarsa.