Alexander Hamilton vs. Aaron Burr: A Deadly Feud

Alexander Hamilton was one of the primary architects of the American Republic. At the moment, he’s never been more popular.

The play about him, “Hamilton,” a rap musical, is currently a smash hit on Broadway. It has won all kinds of awards. Hamilton’s spirit — he’s buried in the graveyard of Trinity Church in lower Manhattan — is, I’m sure, pleased with this happy turn of events.

By the end of his life, however, Hamilton’s political star was in free fall. He was a protege of the legendary General George Washington, serving as his aide-to-camp. As an artillery officer in the Continental Army, Hamilton fired the first shot at the battle of Trenton. He ended his army career participating in the American victory at Yorktown, VA, over the British troops, in October, 1781.

Hamilton was also the creator of the Federalist Party and contributed in a major way to the making of the U.S. Constitution. Washington appointed him as the first Secretary of the Treasury. His achievements in that arena are monumental in scope.

When Washington retired to his farm in Virginia, in December, 1797, after serving two terms as president, Hamilton’s national political influence began to fade. The Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison had taken center stage.

Hamilton, 47, died tragically, on July 12, 1804, as a result of a duel, with a fellow patriot, who was also an attorney — Aaron Burr. It took place in Weehawken, NJ. Burr was charged with Hamilton’s murder. Rather than contest the case, he stayed out of New York and New Jersey. Burr eventually fled to Europe from 1808 to 1812. The charges were later dropped. Burr died in 1836.

Washington never took to Burr and refused him any sinecures. Whether Burr blamed Hamilton for the rebuffs is not known for sure.

To say that Burr was seriously jealous of Hamilton would be an understatement. He comes off as suffering from delusions of grandeur. Burr’s reckless conduct, as he aged, bordered on treason.

Hamilton was a resident of Manhattan. He left behind a grieving widow and seven children, one of whom was adopted. (His oldest child, Philip, had also tragically, died in a duel, in 1801.) The then-young American nation was shocked by Hamilton’s death. NYC was “consumed with grief.” A state funeral, with the militia marching and “church bells ringing out sorrowfully,” was held with the patriot, Gouverneur Morris, giving “a stirring eulogy.”

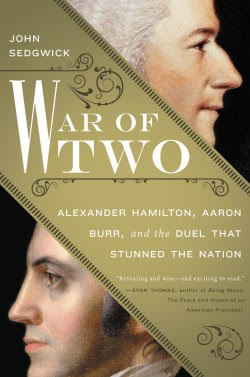

A new book, “War of Two: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and the Duel That Stunned a Nation,” penned by author John Sedgwick, brilliantly captures events leading up to the fatal clash between the feuding duo. The author, in a breezy, scholarly style, traces the origins of Hamilton and Burr: their early family histories; schooling at Princeton; war years exploits; and, their days practicing law in New York state. Sedgwick fills in their backstories with many interesting anecdotes along the way.

Burr came from “a nearly divine American lineage,” Sedgwick wrote, while Hamilton, on the other hand, was a “solitary immigrant of unknown ancestry.” He was born on the island of Nevis in the Caribbean. His mother was of French Huguenot stock. Hamilton was born out of wedlock. His father was supposedly a Scottish sea Captain. But, Sedgwick speculates that a man named Thomas Stevens, formerly of St. Croix. was his real father.

Thomas Stevens was Hamilton’s major patron when he landed in NYC, at age 16, in 1773. Stevens also had a son, named Ned, who was two years older than Hamilton. Their resemblance was striking. Hamilton’s friend, Timothy Pickering, “thought they must be brothers.” Question: Why would Stevens extend “guardianship to a non-relation,” absent a closer kind of bond?

Burr’s main claim to military fame was his involvement in the expedition to take Quebec from the British. The daring campaign, in 1775, up through 600 miles of Maine’s freezing Kennebec River, was led by none other than Benedict Arnold. The weather was harsh, the terrain difficult and food was in short supply. “Only 650 of the original 1,100” brave soldiers survived the passage. Arnold was wounded in the attack. The Americans were roundly defeated, but Burr emerged from the hellish ordeal as a “man of honor.”

Burr did have a very successful political and legal career. He served two terms in the NY Assembly; one term as the state’s Attorney General, one term as a U.S. Senator; and one term as Vice-President, with Jefferson as President (1801-05). Some of the Burr’s legal cases were against Hamilton; a few were, oddly enough, when they both served as co-counsel for a client.

The pretext for the duel was a comment Hamilton made at a dinner party. He referred to Burr as “a dangerous man.” History has surely proved him right on that score.

There is so much more in this book that I’m sure the readers will find highly entertaining. The vicious political backstabbing at that time makes the Clinton/Trump campaign battle look like a grade school picnic. The print media at the time behaved very badly, too. Hamilton and Burr, both had dirty hands for sure in this realm of cut throat politics, as did the supposedly saintly Jefferson.

Sedgwick has written a winner of a book. I am recommending it to America history buffs and political aficionados.

Bill Hughes is an attorney, author, actor and photographer. His latest book is “Byline Baltimore.” It can be found at: https://www.amazon.com/William-Hughes/e/B00N7MGPXO/ref=dp_byline_cont_book_1